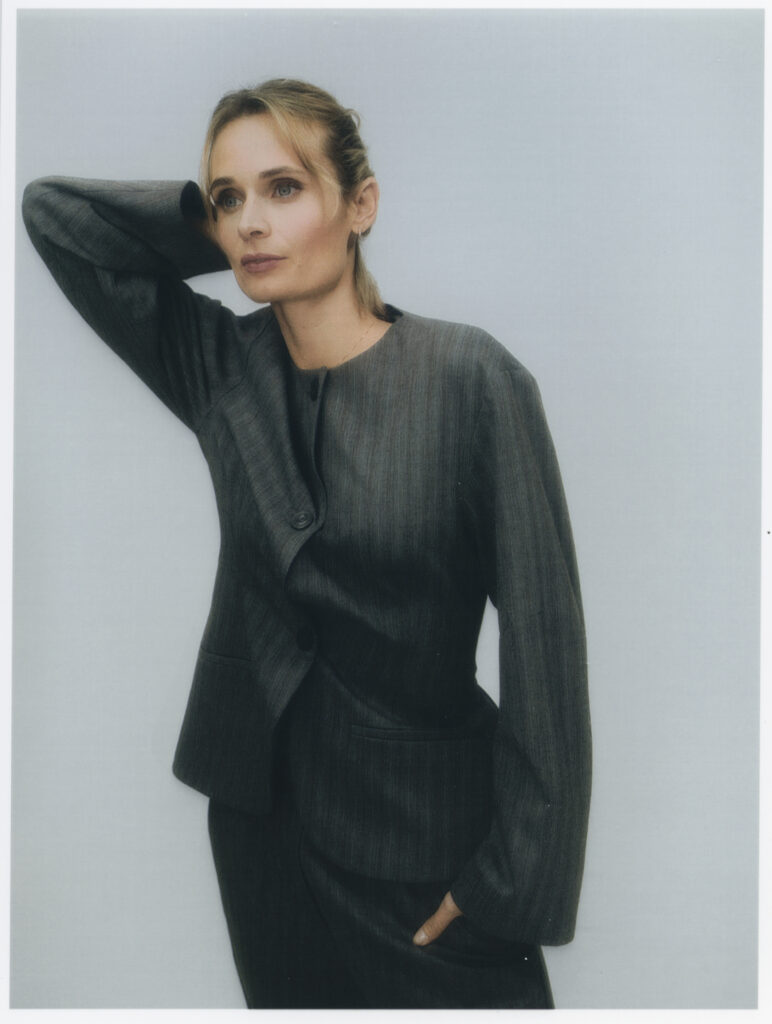

Martin Wickström on Painting, Space and OSLO text Natalia Muntean Martin Wickström describes his way of working as one where you “start somewhere, and it kind of develops during.” Presented at CFHILL Gallery in Stockholm, OSLO brings together painting, literature and photographic material in an exhibition informed by Henrik Ibsen, Edvard Munch, as well as the artist’s long-standing interest in found objects. Active since the late 1970s, the Swedish painter reflects on his process, where images are sometimes held for decades before finding their place. In OSLO, references are absorbed rather than illustrated, and meaning emerges through trust in the room, the material and the passage of time. Muntean Natalia: Why Oslo? What drew you to this title, and what kind of space does it open for the work?Martin Wickström: It’s normally when I do a show, I have a room space, obviously, and a deadline. But when I start working, I don’t know anything about the title or anything. I start somewhere, and it kind of develops during, so it’s kind of scary. Will it end well? I don’t know. But in this case, the theme is easier to read than it used to be. When I started, I had this painting with a big truck house. I collect a lot of pictures and images from several sources. The sofa – that one I also had for many years, kind of lying around. But this time, I started without knowing anything about Oslo, with a sofa. The next step was my wife, Lena – that’s important. She had talked about a play she made for television in 1993, Henrik Ibsen’s Hedda Gabler. I decided to see that, and meanwhile, I started thinking about theatre plays and texts. And all of a sudden, I knew that this truck was a “Dukkehjem” (A Doll’s House), the very famous play, also by Ibsen. And then we managed to get Hedda Gabler from the archives on SVT to see it. I was totally astonished. I also found a photo book by Edvard Munch. He worked a lot with photography, not in a documentary way, but experimental, introspective. One of the paintings here is based on one of his photographs. It shows Rosa, one of his models with red hair, and her sister Olga. At first, I thought it was Munch himself in the photo, but then I read about it and realised it was the two sisters. And then I knew that this was it. It was going to be Norway in one way or another. That’s how OSLO came to be.NM: You mentioned strong women like Hedda Gabler and Nora from A Doll’s House. Were you also thinking of the current political situation?MW: No, it wasn’t that, but it’s even more important to reflect on it. These plays were written in the 1860s-80s and were extremely progressive stories about strong women. Nora, in the end, decides to just leave her husband and kids to start a new life; in its time, that was extremely radical and provocative. Then there is Hedda Gabler, a strong daughter of a military colonel. She inherited duel pistols from her father, and she is almost exploding in her marriage. In the end, she kills herself. These were written 150 years ago, and all of a sudden, women’s history is going down again fast. It’s frightening, and it makes it even more important to take these strong women out. NM: What can you tell me about the use of the colour red in this exhibition?MW: I’ve used it sometimes, but not like this. I started with this small painting of a woman with a telephone, which is cut out from a film still of Jane Fonda. That image was red from the beginning. When I finished that painting, which was the first one I did, I thought, “Wow, I really like the red,” and it also corresponded with the strong theme in the exhibition. Initially, the photos are in black and white, so I turned them into red. Image Courtesy Martin Wickström & CFHILL NM: It sounds like you have some intentions when you start working, but there’s also a lot of play involved. Could you walk me through your creative process a little bit, and what a typical day might look like?MW: I mean, I obviously have a lot of things collected, but I don’t really know how they fit together at first. People ask me, “How do you dare to work like that?” I’ve done it now maybe 60 times over 50 years. You start with what’s important: the space. So I start with the space. I work on the computer: I virtually ‘take down’ the walls of every space I work with and then build it up again. I turn images red, change them, cut them, whatever is needed, and then I place them as miniatures, in the right scale, on the virtual walls to test how they might work together. Of course, as you understand, I don’t have all the works ready at that point, but I can still start by saying, “Okay, I need this, and that, and that. Maybe that’s a bit too much,” and so on. I can begin to see what I need and how it might fit. For example, I knew about the truck house painting, and that was the first one. Then I thought, if I put that one there, and the sofa painting over here, which has nothing to do with Oslo, but I named it after George Harrison’s ‘Norwegian Wood’, the Beatles classic, then it starts to connect. Even if the final exhibition doesn’t end up exactly like the computer model, I’ve learned how to read the room. That’s my process. And when it comes to separate paintings, I also work with them digitally: I change the colours, cut things away, and then make a big photocopy. I look at the photo I made on the computer and work from that. NM: How much do