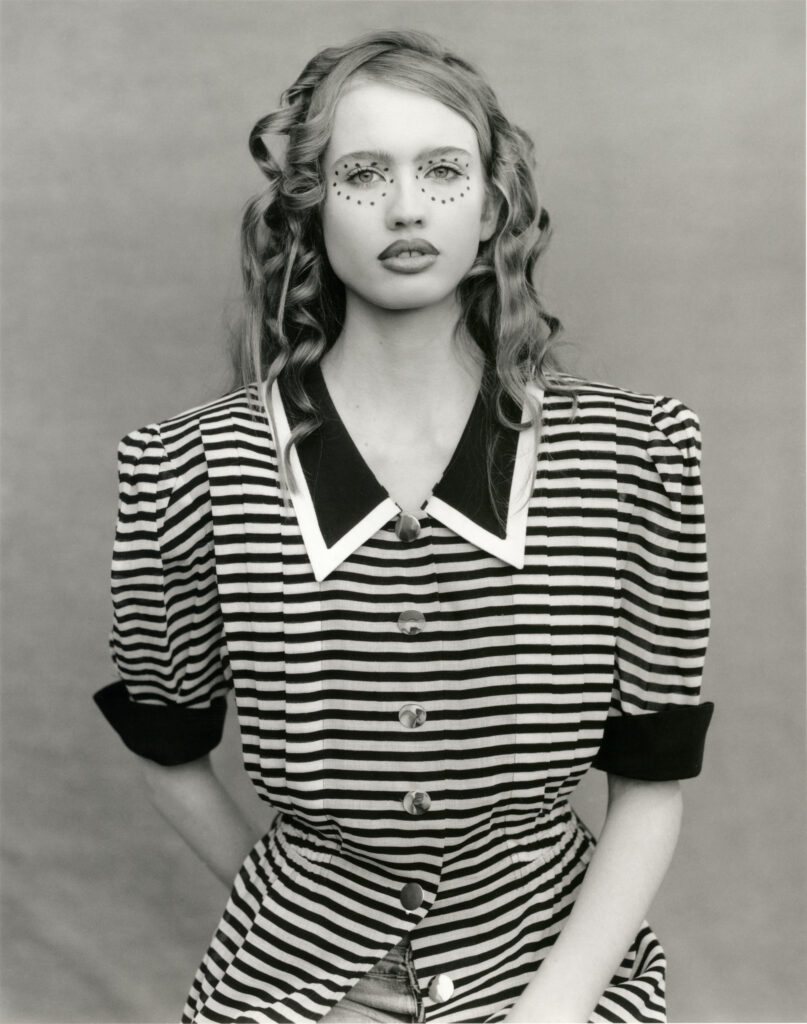

Chanel Beauty Backstage – Métiers D’art 2026

Beauty Backstage – Chanel Métiers D’Art 2026 Apply a small amount of SUBLIMAGE L’EXTRAIT DE NUIT to the cheeks, forehead and neck. With both hands, smooth over the face from the centre outwards. For the neck, follow your jawline. Apply SUBLIMAGE LA CRÈME TEXTURE UNIVERSELLE and perform LE GESTE SUBLIME RADIANCE: bend the fingers and massage from the centre of the face outwards in a wide circular motion. For an extra touch of pampering, apply SUBLIMAGE L’EXTRAIT HUILE LÈVRES occasionally throughout the day. The golden metal applicator fits the shape of the lips perfectly and delivers just the right amount for an immediate feeling of comfort. Apply SUBLIMAGE LA BRUME under or over makeup. Spray on each side of the face, followed by the forehead. With closed hands, help the product absorb by using your knuckles to apply light upward pressure to the face, working from the centre outwards. Apply a small amount of LA BASE MATIFIANTE in any areas where pores appear more visible, like T-zone (forehead, nose, chin) and around the sides of the nose. Gently tap or smooth the product with your fingers. Apply LES BEIGES WATER-FRESH COMPLEXION TOUCH with the 2-IN-1 FOUNDATION BRUSH 101. Correct any imperfections of the face using ULTRA LE TEINT LE CORRECTEUR with the RETRACTABLE DUAL-ENDED CONCEALER BRUSH N°105. Dip the PETIT PINCEAU KABUKI into LES BEIGES HEALTHY GLOW BRONZING CREAM then apply it all over the face, concentrating on the forehead, temples, nose, and chin. Apply BAUME ESSENTIEL TRANSPARENT on your cheekbones. images courtesy of Chanel eyes Brush the brows with the DUAL-ENDED BROW BRUSH N° 207, then fill in with the STYLO SOURCILS HAUTE PRECISION. The eye is styled with a sharp, elongated cat-eye eyeliner. Draw a thick line along the upper lash line using SIGNATURE DE CHANEL and extend outwards into a precise, lifted wing, creating a strong, graphic effect. The eyelid are bare, letting the eyeliner stand out as the main focus. The lower lashes are kept natural, adding balance to the bold upper line. nails Prepare with a coat of LA BASE CAMÉLIA. Set up with LE VERNIS 154 POMPIER or LE VERNIS 147 INCENDIAIRE (according to the looks). Fix and add shine with LE GEL COAT. lips Add BAUME ESSENTIEL TRANSPARENT all over the lips.