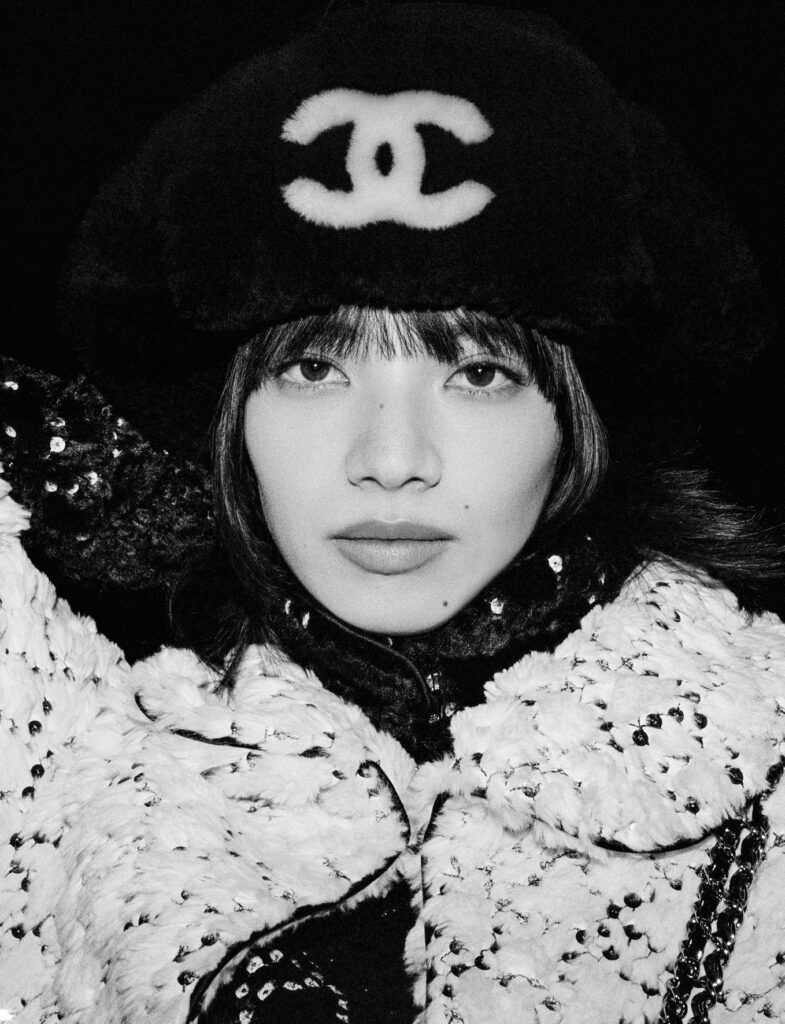

Ludi Leiva: on Intuition, Ancestry and Home as a Verb text Natalia Muntean “Art is essential. It’s how we record history, emotion and collective experience,” says Stockholm-based artist Ludi Leiva. Rooted in her Canadian, Guatemalan, and Slovak heritage, Leiva’s practice traces the spaces between displacement and belonging, with creation as an act of both remembering and reimagining. A former journalist turned artist, she earned her MFA in Visual Communication from Konstfack University in Stockholm and now continues her studies at the Royal Drawing School in London. Her commercial collaborations with Apple, Vogue, and adidas coexist with deeply personal explorations of ancestry, ecology and belonging. Working across painting, printmaking and text, she treats intuition as both a compass and collaborator. “It can bring people together, start difficult conversations, and help people process difficult topics. It can protest. It can do everything,” she reflects on the role of art. “That’s why I think it’s one of the most precious things humanity has, and it deserves to be championed and protected well.” photography Sandra Myhrberg Natalia Muntean: How did you become an artist?Ludi Leiva: I think I was born one. It was more about finding my way back to a more honest way of being. I actually started professionally as a journalist, so writing came first. Around 2016, I began working as an illustrator, mostly doing editorial commissions and client projects. Over time, though, I started to feel a kind of creative fatigue. I began asking myself who I was outside of a brief, what I actually wanted to express that wasn’t being dictated by a brand or an assignment. That curiosity eventually led me to Sweden, where I did my master’s in Visual Communication. Ironically, after two years of studying illustration, I realised I had only scratched the surface of what I really wanted to explore. Being surrounded by people working in so many different media opened up a lot for me. During my final exhibition, I found myself much more excited about designing the installation and its conceptual direction than about the illustrated book I’d been working on. So I followed that feeling and decided to trust my intuition. That led to two years of real growth as an artist. In 2024, I received a working grant from the Swedish Arts Grants Committee that allowed me to focus fully on my studio practice without relying on commercial work. It’s been a really deep, exploratory period. NM: Was that scary to do?LL: It was scary to stop investing in the thing that was giving me social validation and dive headfirst into something very unknown and difficult. As a self-taught artist, I didn’t have that institutional background. That’s something I’m still dealing with, particularly here in Sweden, where I think a lot of emphasis is placed on attending places like the Royal Art Academy and the networks you make there. It’s interesting for me to wade through that, but I’m proud of what I’ve accomplished in the last couple of years by just winging it and following my gut. I’m excited to see what else this journey brings. NM: What surprised you the most in these two years? Maybe you learned something about yourself or your practice?LL: I was able to really uncover a way of working that feels very intuitive. A few years ago, I would sit at a blank piece of paper and feel panic, not knowing what to do because I was used to at least being given an idea. Over the last several years, I’ve developed this strong inner sense of what a material, or what something, wants to be, and I listen to that. I’ve found different methods of working where I feel the material is a collaborator. For example, I work a lot with monotype printing, where each painting can only be transferred once, so it’s an original, and I really love that. You can work as much as you want, but you can only control so much of the process. There’s a level of surrender in the transfer because it’s never exactly how it was. Something can change depending on the paper, the water or the printing surface. I find a great sense of freedom in co-creating with something other than just my mind trying to enforce an idea. You have to have a sense of non-attachment and openness to it becoming something slightly out of your control at all times. I know exactly how long to soak the paper and what pigments to use, so there is some reliability, but there’s always a one or two per cent chance that something could go slightly differently than expected. I find that quite lovely. NM: You work in different media now, painting and printing. How do you choose which medium you’re going to use?LL: I go back and forth quite a lot. It depends on my mood or where I am mentally, and I think different thematic explorations are better suited for one medium or another. For instance, I recently started a series because I remember my dreams a lot, and I’ve kept a dream journal for years. I have really intense dreams, and I often remember them like full films in my mind in the morning, and I write or sketch things out. I always consider my dreams, but I try not to plan too much around them, because it can be a little scary if something happens and you wonder if it’s the future. But I do find a lot of inspiration in them, especially in the visuals, the strange landscapes and geographies, often like psychedelic dreams. I started a series where I take visual images from my dreams and paint them onto bed sheets, either old ones of mine or found ones from second-hand stores. I like finding ones with old initials. It’s a way for me to explore if dreams leave any kind of physical or energetic residue in domestic space, because we spend so much of our lives in