I Told You I’d Be Home Most of the Day – A Meditation on Longing by Josef Jägnefält

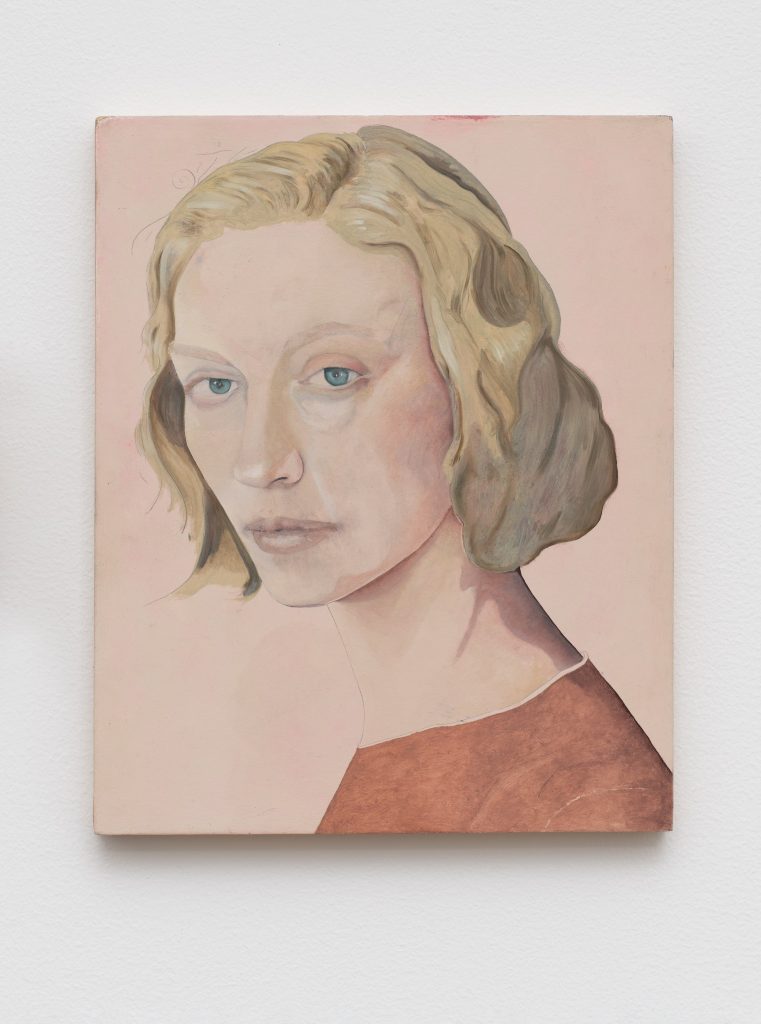

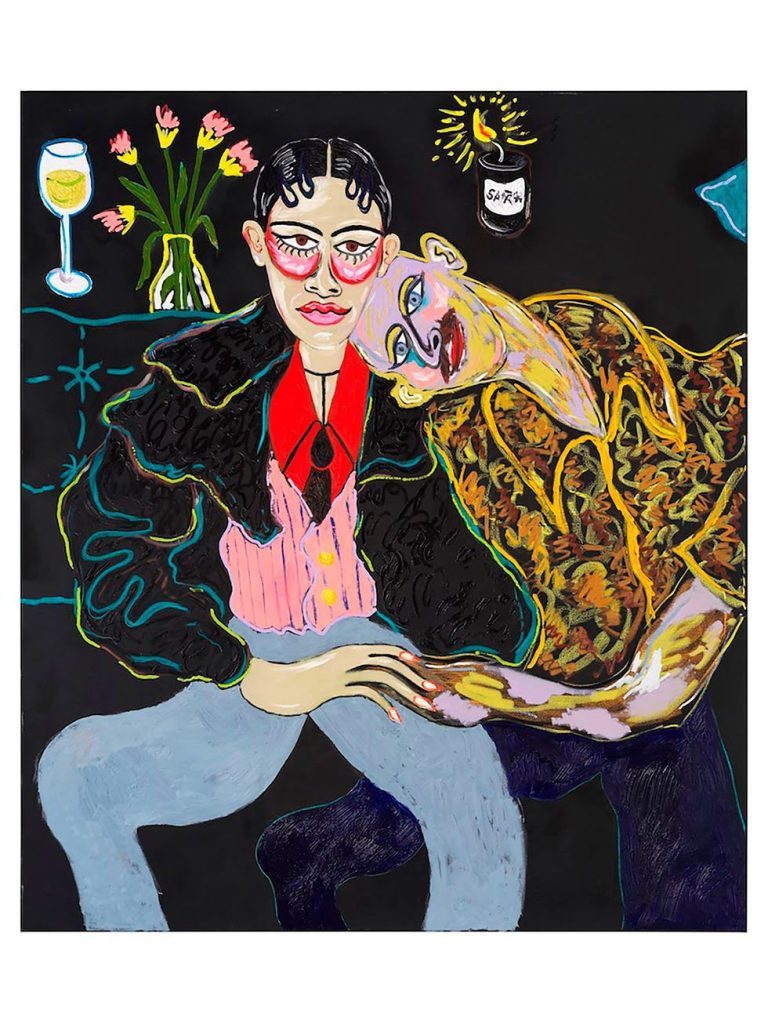

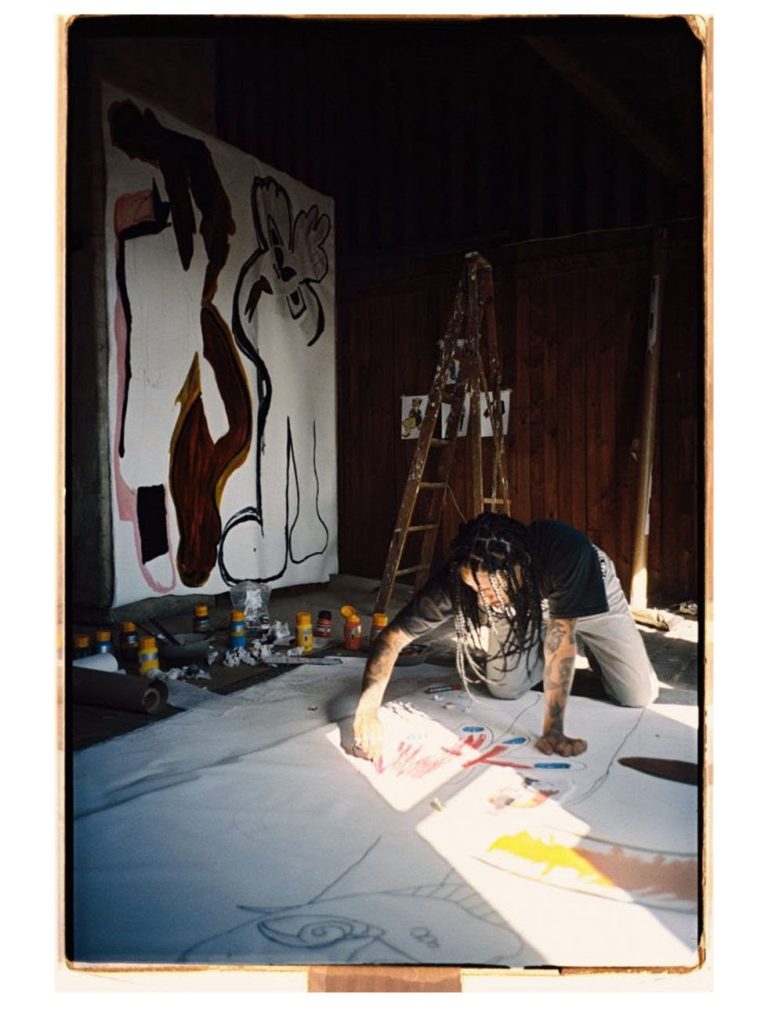

I Told You I’d Be Home Most of the Day – A Meditation on Longing by Josef Jägnefält text Natalia Muntean Swedish artist Josef Jägnefält’s first solo exhibition at Saskia Neuman Gallery, I told you I’d be home most of the day, invites viewers into a world where ordinary objects become powerful carriers of hidden stories and emotions. Throughout the exhibition, we are invited to explore the delicate balance between stillness and longing, where the most intimate objects become reflections of human desire. “I don’t think about a story,” says Jägnefält, “I think about the colour and how to get there.” This focus on details and colour lends the works a quiet yet powerful emotional resonance and captures the tension between what is revealed and what is left unsaid, offering a visual meditation on longing and desire. I told you I’d be home most of the day will be on display until September 26th at Saskia Neuman Gallery in Stockholm. Natalia Muntean: Could you tell me a bit about how you started as an artist? Was there a decisive moment when you realised this was what you wanted to do?Josef Jägnefält: I applied to art school, encouraged by friends and family. I initially studied printmaking, but when I applied to university, I focused on painting full-time. NM: Did you grow up in a family of artists?JJ: My mother was a teacher who sometimes taught art classes, though she wasn’t a trained art teacher. She enjoyed it, and her mother was also an amateur painter. It was always present in the family, but no one pursued it as a career until me. My brother is an architect, which is somewhat close. NM: Do you have any routines or methods that help get you into a creative mindset?JJ: Going to the studio every day and just continuing to work is key. Eventually, something happens. My process is slow, using small brushes. It sometimes feels like I haven’t done anything for a week, but when I return to the work, I realise things have moved forward. NM: How does the journey go from gathering images to creating a painting? And how do you decide which ones will become paintings?JJ: I save images on my phone or computer, and they can come from anywhere—books, online, or even everyday observations. Everything gets processed digitally, but I like to print the image to have a physical copy. From there, I might make a simple drawing or use transfer paper to trace it onto canvas or another surface.It’s a very intuitive process. I might find an image, save it, and maybe a year later it resurfaces when it feels ready. It’s not immediate; it’s more about timing and seeing when an image feels right. I print a lot of images and experiment. Instead of starting with a big painting, I might begin with a smaller one to test it. Over time, I’ve painted over so many works, only to later find a picture of the original painting and realise it was interesting. But by then, it’s gone because I painted over it. I’ve ruined many paintings like that and regretted it later. Now, I try to stop before I get to that point, so I can restart the same painting if I need to. NM: How do you decide which materials to use for a painting? What materials or techniques are important for expressing the feelings you want to convey?JJ: I used to buy large canvases and aim for perfection, but it became time-consuming and creatively limiting. After moving to Stockholm, I began using scrap materials like MDF or wood from building sites, which brought more variety into my work. The paint itself is very important. I usually use acrylic paint, which can be in any colour, for my larger paintings. With acrylics, I can be adventurous and use different colours, mixing them as I like. With oils, I limit myself to five colours, inspired by LS Lowry, a British painter known for his industrial landscapes of people in Manchester. This approach has significantly impacted my paintings, as it has forced me to really focus on finding the right colour. I enjoy the challenge of reproducing a printed pattern as closely as possible, but sometimes I can’t get the exact colour I want, which leads to something unexpected and I enjoy that. NM: Are there any materials you’d like to work with in the future?JJ: I’m always curious about new materials. My girlfriend is also an artist, and though she doesn’t paint, she uses a lot of different materials in her work. That’s a great source of inspiration, and we often share materials. NM: Do you give each other feedback on your work?JJ: Always! It’s important to have people you trust. I invite a few close friends to the studio to ask for their opinions. Sometimes you need an outside perspective to see if a piece is finished or if it works. NM: How do you know when a painting is finished?JJ: Sometimes I’m afraid of ruining it, so I stop. There are examples where I stopped too early, but that became a part of the piece. When I put the frame on, it’s like saying goodbye to the painting. NM: When you blend different sources like art history, photography, and magazines, do you feel you’re creating a new story, or are you highlighting elements of existing ones?JJ: It’s a mix. It becomes a narrative, but it’s not a clear-cut story. I don’t have a storyboard or an ending. I want to surprise myself by putting images next to each other, and something happens. I’m not sure what it is, but it’s fun to do. NM: I imagine that it’s like a puzzle? You mix and match the pictures?JJ: I keep painting, and when the paintings are ready, something happens. I might work on several paintings at a time. Many of them get discarded, put on a shelf, and then, much later, I find something interesting