Matt Belk: I Think Artists Are Professional Observers

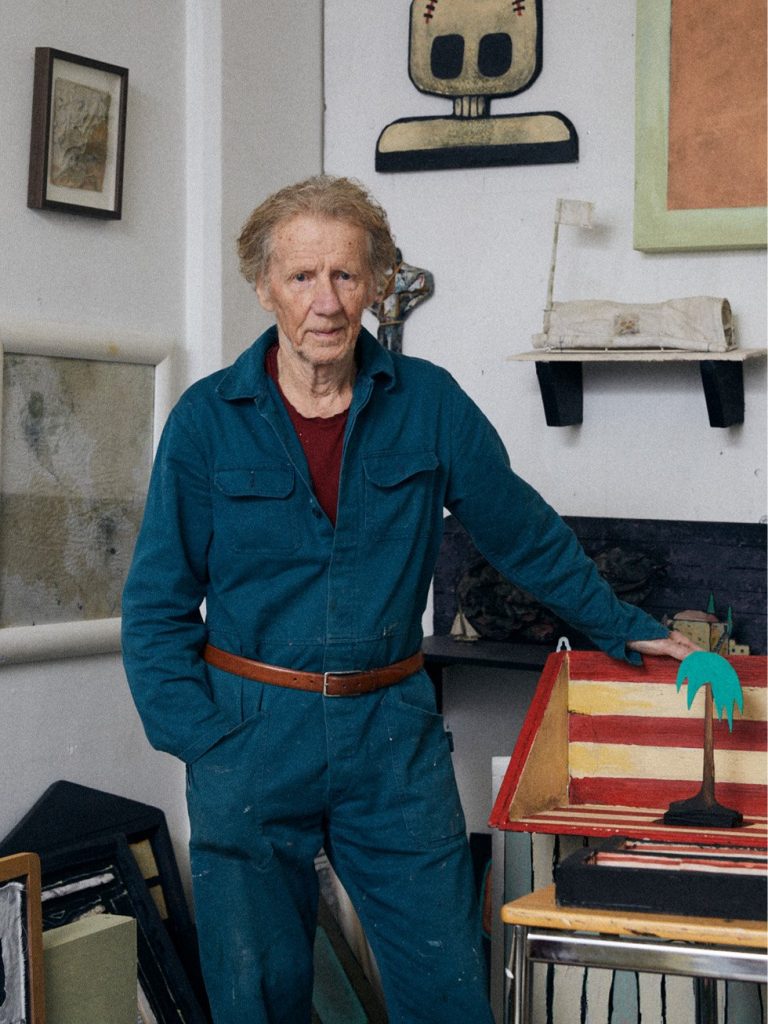

Matt Belk: I Think Artists Are Professional Observers text Natalia Muntean To kick off Stockholm Art Week, we have asked a number of interesting people from the city’s art scene questions to explore their relationship to art and the city.Matt Belk is a contemporary wildlife painter combining the outdoor country lifestyle with modern contemporary aesthetics. Born in 1988 in Omaha, Nebraska, his artwork involves the constant use of tape, cutting of shapes with an X-Acto blade, and airbrushing with inventive new techniques to create a seemingly digital graphic representation of the laws of nature. He is currently participating in an art residency program based in Sweden. What is the story behind your exhibition during Stockholm Art Week?The title of this show is “From Nebraska to Sweden” and it’s about showing where I’m from in Nebraska, to my stay in Sweden the past 4 months. This show depicts so many new things I’ve seen in Sweden, exploring all the different wildlife, flora and fauna – mainly on the archipelago island of Blidö, but I’ve also been so fortunate to be able to travel further south to friends’ homes in Sperlingsholm, Erstavik and Borrestad and discovered different terrains from each unique new place I went, and then unfold what I saw and experienced in my work for this exhibition. What inspired you to become an artist, and how has your artistic journey evolved?My mom was an artist when I was young and I was so amazed watching her draw, I remember looking at her drawing and thinking that it was a magic trick. From the inspiration of my mom, I started drawing for many years, mostly figuratively and then I started to experiment with oils, until just a few years ago my dad bought me an airbrush. I thought I would try it out once and probably never use it again, but here I am 4 years later – and now all I use is airbrush and all I paint is nature, for now. What is your creative process like, and how do you approach developing new ideas and concepts for your work?My process is observation, I think artists are professional observers. What really excites me is travelling to new places and exploring new areas, all of the unique plants, birds, animals and landscapes. That’s what is inspiring to me about nature, it becomes an adventure in itself that is then linked to the art. My picture-building process is to go between an iPad, a sketchbook and a bunch of magazines or photos I’ve taken to Xacto blades and airbrush on layered gesso canvas. What role do you think art plays in society, and how do you see your work contributing to or challenging societal norms? I can only speak for myself, who I am as an artist, and my duty as an artist – I believe my calling or my job as an artist is to create work that inspires others, to create work that everyone anywhere can get something from – that isn’t off-putting to anyone. Really, I want to see kids be able to take something from my art, and that it could push them towards exploring the arts too. Are there any themes or subjects that consistently appear in your work, and if so, what draws you to them?I grew up hunting, so there is always some aspect or element about hunting in my works. Hunting is a very ritualistic and grounding thing for me. Growing up, watching the dogs hunt was even more enjoyable than hunting itself. It’s what I know and what I want to show and explore without being off-putting towards anyone, so I want to be clever about how it’s presented, Trojan horse, the concept to my art in a way. Can you share a favourite spot in Stockholm where you go to find inspiration or recharge creatively?One of my favourite things to do since being here is hopping on a bus on Blidö, especially when I need to do some “idea-shopping”. I found that it was the perfect way to map out my next paintings, and a great place for me to think. I took the buses all over Bildo, most often ending up in Norrtälje where I’d spend some time at the ICA Flygfyren Bistro. Can you share a story about a specific neighbourhood in Stockholm that holds personal significance to you as an artist?I love Old Town – Gamla Stan, it’s just magical there, and amazing for bird watching. I also love seeing the old architecture. Is there a Swedish artist who you find inspirational?I really like Joakim Ojanen and Leo Park, I just like how they’ve created their own little worlds – I have a lot of respect for them because they seem like they’re always working and I look up to that, the people who are always working, and you’re kind of chasing in some ways. What is your favourite bar or restaurant in Stockholm?Beirut Café in Östermalms Food Hall. NEBRASKA, 2024 acrylic airbrush, tape and xaco blades on canvas 39,5h x 47,3w in (100h x 120 w cm)