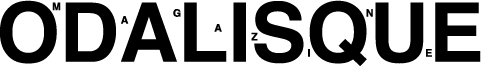

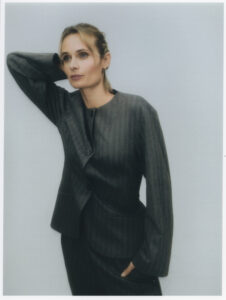

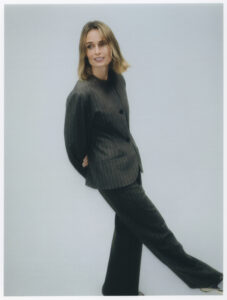

Malin Barr Debuts at Sundance Film Festival with Sauna Sickness

Written by Natalia Muntean

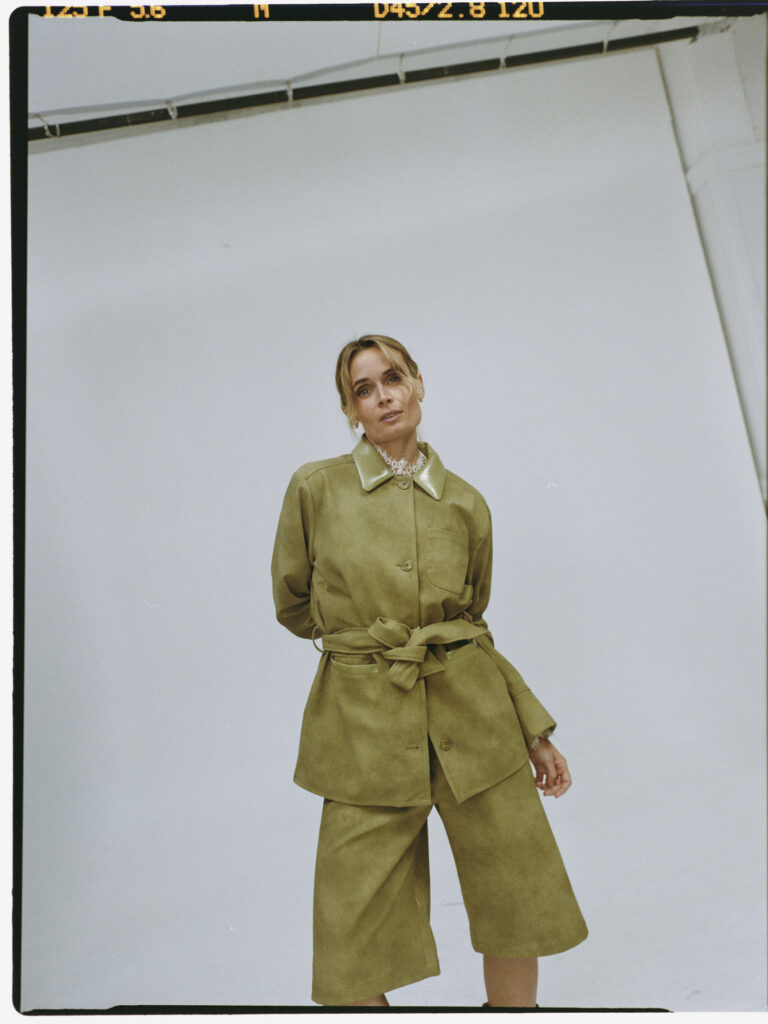

What does it feel like to stop trusting your own instincts? In her Sundance debut, SAUNA SICKNESS, a psychological thriller peppered with dark humour, Swedish actor and director Malin Barr deconstructs the architecture of manipulation and gaslighting. Eschewing overt violence for a quieter emotional “erosion,” Barr examines how women are socialised to perceive control as care. “I became fascinated with that disorienting state, what it feels like to stop trusting your own instincts, and that’s when I knew it needed to be portrayed on film,” says Barr, reflecting on the psychological dissonance that drives the film’s narrative.

Natalia Muntean: Sauna Sickness is inspired by a moment from your own past relationship. What made you realise this specific moment needed to become a film?

Malin Barr: I never really felt that this specific moment needed to become a film. For a long time, while I was still in the relationship, it was just something I’d tell as a funny story to friends. It was only later, after I got out and started talking more honestly about what I’d experienced, that the realisation landed. It wasn’t funny at all. It was manipulative and unsettling. The dissonance I had lived with, how easily I smoothed over disturbing behaviour and lost my inner compass, was a survival mechanism. That realisation stayed with me. I became fascinated with that disorienting state, what it feels like to stop trusting your own instincts, and that’s when I knew it needed to be portrayed on film. The sauna and the cold outside felt essential to that. The hot-and-cold swings mirror a manipulative relationship and New Year’s carries that false sense of expectation, pressure and the promise of a new beginning.

NM: The film isn’t about overt violence, but about subtle emotional erosion. Why was it important for you to portray abuse in this quieter, more ambiguous way?

MB: There were a few reasons. First, I believe personally rooted stories often make the most honest films – but for them to really land, they need to feel universal. It was also important to me that the behaviour didn’t feel too extreme. Subtle, quieter forms of abuse are something people might recognise in some sense from their own lives, even if they haven’t named it that way. Portraying it this way invites the audience to lean in, rather than lean back in shock. It asks them to pay attention instead of distancing themselves by thinking “this isn’t about me.” Emotional erosion usually happens in the small moments – in tone, in denial, in what’s left unsaid. That ambiguity mirrors what it feels like to be inside it.

For that same reason, I chose to layer in moments of darkly comedic absurdity. Humour is something we constantly use to cope, to smooth things over, to survive uncomfortable situations. It makes the film more relatable rather than relentlessly heavy, while also reflecting the absurdity and disorientation of not trusting your own perception. And it gives the audience small moments of relief!

NM: Cleo repeatedly takes responsibility while Tobias deflects it. How intentional was that dynamic in shaping the audience’s understanding of control?

MB: Very intentional. It was important to me that Cleo never reads as weak or passive. She’s extremely active, constantly trying to take responsibility, adjust, and find ways to make things work. When she pushes back and asks for clarity, that’s when Tobias switches tactics: moving from charm and avoidance to confusion, victimhood, and reframing. These are all ways to regain control.

At the same time, Tobias’s refusal to ever take responsibility is deliberate. That kind of deflection is a classic control mechanism. By the third time this dynamic repeats, my hope is the audience recognises the pattern – and potentially comes to the same realisation as Cleo does.

NM: The couple Cleo meets on the road feels almost surreal, and it seems to catalyse Cleo’s clarity. Why was it important that her realisation came from an external reflection rather than Tobias himself?

MB: The meeting with the neighbours is experienced entirely from Cleo’s perspective – it’s filtered through her perception of the world, her current emotional state and what she’s endured so far.

It was important that Cleo’s clarity came from an external reflection rather than Tobias himself because she’s too close to him – she’s normalised his behaviour and can’t fully recognise it. The neighbours act as a mirror: their boundary-pushing echoes Tobias’s – and their recognition that his behaviour isn’t “normal” gives Cleo the distance to have a crucial moment of insight. This becomes the first turning point where she can begin to see his patterns for what they truly are.

NM: Leaving Tobias behind is not framed as revenge, but as clarity. Why was restraint important to that choice?

MB: Because this isn’t a story of retaliation, it’s a story of self-preservation. Revenge wouldn’t get her anywhere, and even though I intentionally tease the idea with the axe in the snow, it’s ultimately not about him. By leaving the cabin, she removes herself from him and focuses on her safety – the only way she can truly reclaim her agency.

NM: Do you see Cleo’s final act as an ending or as the beginning of something else?

MB: I’d say that’s up to the audience to decide for themselves. We literally leave her at a crossroads.

NM: How has your background as an actor influenced the way you write and direct emotionally intimate scenes?

MB: My acting background has absolutely shaped how I write and direct. I know what makes me feel equally supported and inspired as an actor and I try to bring that understanding to my work behind the camera. For emotionally intimate scenes, knowing what it’s like on the other side is invaluable. Creating a safe environment, respecting their boundaries and being clear about what the camera sees at all times are all crucial for the actors to feel free and confidently explore the scene. As a writer, it especially helps me to write dialogue that feels real and natural and in connection to intimacy, make deliberate choices about when and why an intimate moment is needed and what the audience truly needs to see.

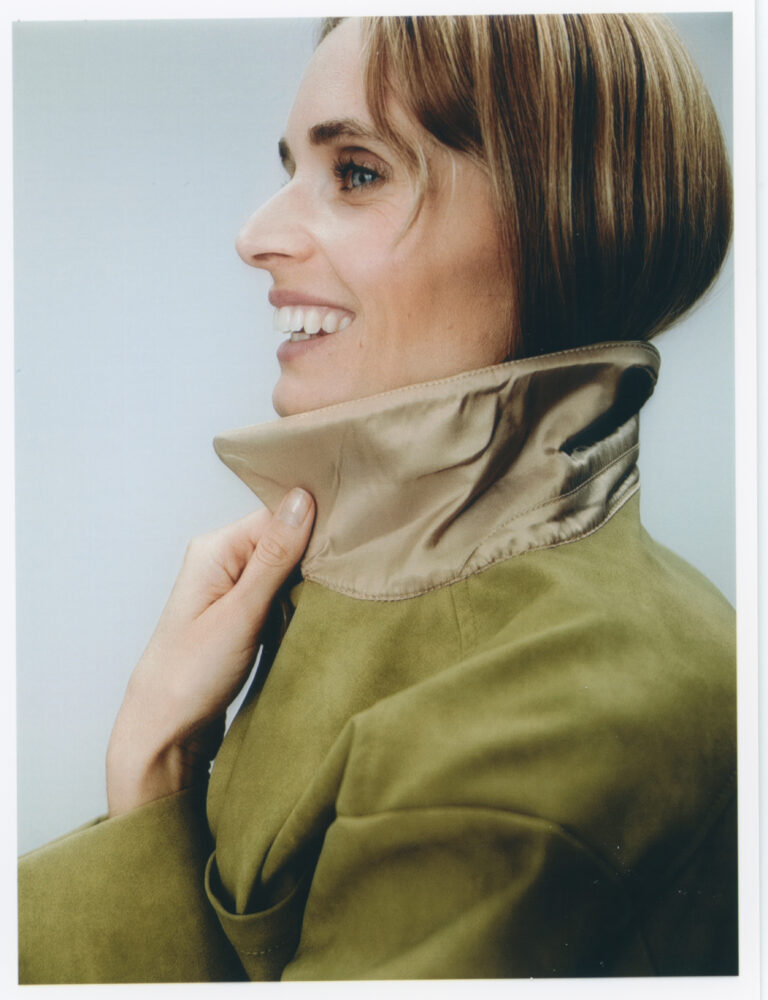

NM: Sauna Sickness marks your Sundance debut. What does that moment represent for you personally?

MB: Without trying to sound cheesy, Sundance has always been my dream festival and my top goal for this film to premiere at. I’ve long admired the fresh, bold and unique films that have come out of the festival. So, to have Sauna Sickness selected from thousands of submissions and be part of this year’s lineup feels absolutely surreal – a real milestone as a director and an incredible opportunity to share my work with a wider audience!

I’m intrigued to see how the Sundance audience experiences the film and to spark some interesting conversations around the themes and the story. I also look forward to meeting other filmmakers, connecting with the industry and seeing where this journey leads next. But yes, it’s an incredibly exciting moment for me personally and professionally!

NM: You’re developing a feature version of this story. How do you imagine expanding Cleo’s journey in a longer format?

MB: The feature version is also a slow-burn psychological drama-thriller with darkly comedic undertones. At its core, it’s a story of self-preservation, told through the lenses of perception, identity, and performance. It picks up a few days before the events of the short, expanding on the aftermath of the “lockout accident”, the unravelling of the relationship and the escalating tension when Tobias’s friends arrive.

NM: If viewers take one thing with them after watching Sauna Sickness, what do you hope it is?

MB: I hope viewers leave with a lingering unease and a recognition of subtle patterns of behaviour – ones we might relate to, overlook, or dismiss – but ones that spark questions about ourselves and our relationships to others.