Amine Habke: The Garden of Intimacy, Repairing Masculinity

text Natalia Muntean

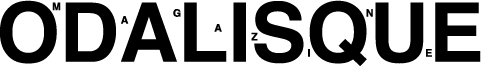

In the delicate, deliberate stitches of Amine Habki’s textile works, a new language of masculinity is being woven. For his first solo exhibition in the Nordic region, I Will Sew Up All the Petals of Your Garden, the French-Moroccan artist transforms the Andréhn-Schiptjenko Gallery in Stockholm into a meditative interior where softness is strength and vulnerability becomes a form of resilience. Drawing on the visual heritage of Islamic ornamentation, European Romanticism, and the diasporic experience, Habki’s practice, spanning embroidery, painting, and sculpture, cultivates a space where the body and the botanical merge. “I don’t have any memories where I wasn’t an artist,” he reflects, “I felt obligated to be an artist and to live by my art.”

Natalia Muntean: Can you elaborate a little bit about the meaning behind the title of the exhibition?

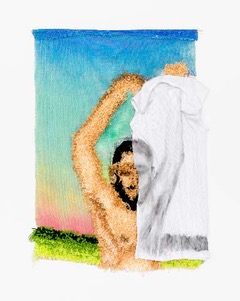

Amine Habke: The title, I think, represents the energy and the entire mission of the show. The idea of a garden, for me, represents the area of intimacy, an inner world. But at the same time, the garden is famous in the iconography of romantic paintings. For this show, I was really inspired by The Garden of Earthly Delights by Bosch. The idea of the show is also to talk about the idea of rehabilitation. I am trying to repair an image of what masculinity is.

NM: Why is it important for you to challenge these ideas about masculinity through art?

AH: This is not about changing something for the world; it’s just for me. It’s a quest for me to take care of this image, of this body. I like the idea of doing a new vision, a new iconography, just for my own healing, just to feel kinder, more connected to what I want to look like. This is a little poetic way to talk about this, and it really helps me, and I think this also helps other people.

NM: What are you looking for in this connection to your work?

AH: I’m looking for more liberty to represent masculinity, to represent romance, to represent love, vulnerability and fragility.

NM: Your practice spans embroidery, painting, and sculpture. How did you begin?

AH: I started with a lot of drawing, but I wasn’t really fulfilled because I was trying to find a volume and to have more relief. So, embroidery was a way to give more shapes and three-dimensionality to my drawings. Embroidery also comes as a visual heritage. My family has a lot of tapestries. I feel connected to these objects. The houses of my grandma and my aunties were places of something soft, domestic, warm, and resilient. I was trying to incorporate this aesthetic onto bodies that are generally represented outside, in heavy material, in big forms. The media often destroys the non-white body, centralising some communities and cultures while excluding others. For me, this is a way to make an opposition to Orientalism. Orientalism destroyed our culture and our heritage. When you’re born in the third generation of Moroccan diaspora, you have certain expectations, but then you discover the reality is more complex. I think exploring these objects and the story of civilisations helps.

NM: The slow process of embroidery – does it influence the narrative of your work?

AH: In my studio, I have a lot of drawings on the wall, and I also write a lot of poems. Sometimes poems give me images, and some images give me poems, so it’s a mutual dialogue.

I start by selecting one of the drawings, and I go to the shop for textiles and fabrics. The element of chance comes in because sometimes I can be obsessed with one fabric, and I think, “Okay, it could match with this drawing, with these colours”. Then I create the image. But there’s a lot of improvisation and freestyle. I have the idea and the concept, but I never strictly know what colours I will use, or if I will add extra things.

NM: You incorporate found objects into your textile works. What is their role?

AH: I think they can symbolise an idea. For example, one piece in the Stockholm show features a lace fabric with flowers already on it. I add painting and embroidery to put a spotlight on, and to make a combination with what I want to symbolise. Found objects are also a way to make more funny combinations. I think this is more the fun and spontaneous aspect of my practice.

NM: You get inspired by the ornaments in Islamic art, transforming arabesques into living patterns. How does your French-Moroccan heritage inform your visual style?

AH: I’m really inspired by the ornamentation, like the grotesque. I discovered that this is not a well-known or celebrated form because, for many people, grotesque is just like minor art; it’s not a major form. I like this idea of putting a spotlight on a minor form. For me, ornamentation is the beginning of surrealism. You have a lot of different motifs and patterns, and sometimes it can look like something real. The grotesque embodies that by mixing humans with animals, with flowers. You also see this phenomenon in some Islamic cultures, for example, the zellige tiles, where the symmetry and repetition make human or body shapes appear. This is the ornamental aspect that inspired me. I’m also really inspired by my French background, like the Surrealism of Magritte. I like Romantic artists like Friedrich. At the same time, I also like Persian miniatures. It’s a mix of the Mediterranean area.

NM: The flower is a recurring symbol. Beyond beauty, what does the flower represent for you?

AH: Flowers have different meanings. I tried to show that it can also be a trap. I did some pieces with men holding flowers; it can be a really soft object, but also really dangerous at the same time. Flowers are present in mythology, like Ovid’s Metamorphoses, and also in the poetry of Mahmoud Darwish. I like the idea of the flower as a protection of love and fragility, but also as something really dangerous. It also represents a cycle. Flowers represent youth, but they die, and another flower comes. This aspect symbolises time passing.

NM: Can you walk me through the creation of a piece? How do you typically begin?

AH: I have a sketch, and I have fabrics. I make some tests at the beginning. Then I start. It depends on the piece, because sometimes I am obligated to paint first, and sometimes I am obligated to embroider first, depending on the fabric. But it’s always one side for painting and one side for embroidery; I don’t do both at the same time. When I’m happy to start a piece, I like to dress as my piece. I wear the same colour palette that I will use. It puts me in the mood, in the mindset of my piece. I also listen to music and play some podcasts.

NM: How do you decide when a work is complete?

AH: I never truly know; it’s always hard. I like not to be alone and to talk with my artist friends in my studio. They can give me advice. For example, a piece for the Stockholm show was not ready for me, but a friend told me, “No, this is ready”. This is one of the favourite pieces of the show. It’s a feeling, mostly.

MN: Does the work help you find answers or understand things?

AH: It is the latter. I think this is a process; I don’t have any answers. When I’m doing the research for a show, that’s when I find some stories and facts. For the show, I Will Sew Up All the Petals of Your Garden, I discovered a community of men in Saudi Arabia who cultivate flowers and make crowns from them. This is really something beautiful and poetic that I love. I also read the book More Rare Are the Roses by Darwish. The next step is talking about the stars and the sky. I’m working on the idea of making a new meaning of what exploration is – how we can have a slow exploration, and how it can oppose the idea of heroic navigation. In every subject, I appropriate my question.

NM: The exhibition is described as an invitation to a meditation on touch, slowness, and care. What do you hope viewers take away from spending time with your works?

AH: I think the process helps me also to resist the rhythm of society. I just have my needle and a lot of time, and I have to be patient and wait. This is not habitual for me, because in other parts of my life, everything goes so fast. So this is really something to help me also to resist the fast rhythm that we have. I hope the viewers have the same need. I also invited a writer, an artist who is a friend. She made it into a journey. For each piece, she wrote a text, so you can follow the text and the piece.

NM: What do you hope that the men who visit take from an exhibition that deals with the vulnerable side of masculinity?

AH: I don’t expect a lot. But I remember during the opening, people would ask, “Who is the artist who did that?” For them, this is something that must be made by a girl or a woman. And I’m like, “This is me”. I think it can change their vision. They can think that it’s also possible to do crafty things, and not think that this is only for women.

Also, a lot of queer people relate to my work because, as I’m part of that community, they can see a romantic representation of the queer body. I have lots of gay men who take their men on a date to my exhibition, which is so cute.

I worked with a team of women, and they also related. My best friend, who is a woman, wrote the text to give a woman’s gaze on the show. And I’m adding this queer gaze on the body. If it makes one man or one person think about things a little bit differently and maybe makes them a little bit more comfortable with their vulnerability, then that’s what I want from it.

NM: Looking forward, what new territories, materials, or themes are you interested in exploring?

AH: Mythology is really a good base for me because it helps me take what I want, and I can appropriate it. I’m taking mythology from all around the Mediterranean – Greco-Roman, Arabic, and Islamic.

The next step after the stars is to work on Circe. I love the fact that she transformed men into new creatures. Maybe I will work on that, trying to make a transfigurative presentation of men. I think mythology is infinite.