Leigh Bowery! Tate Modern Unveils a Bold Tribute to the Iconic Performer

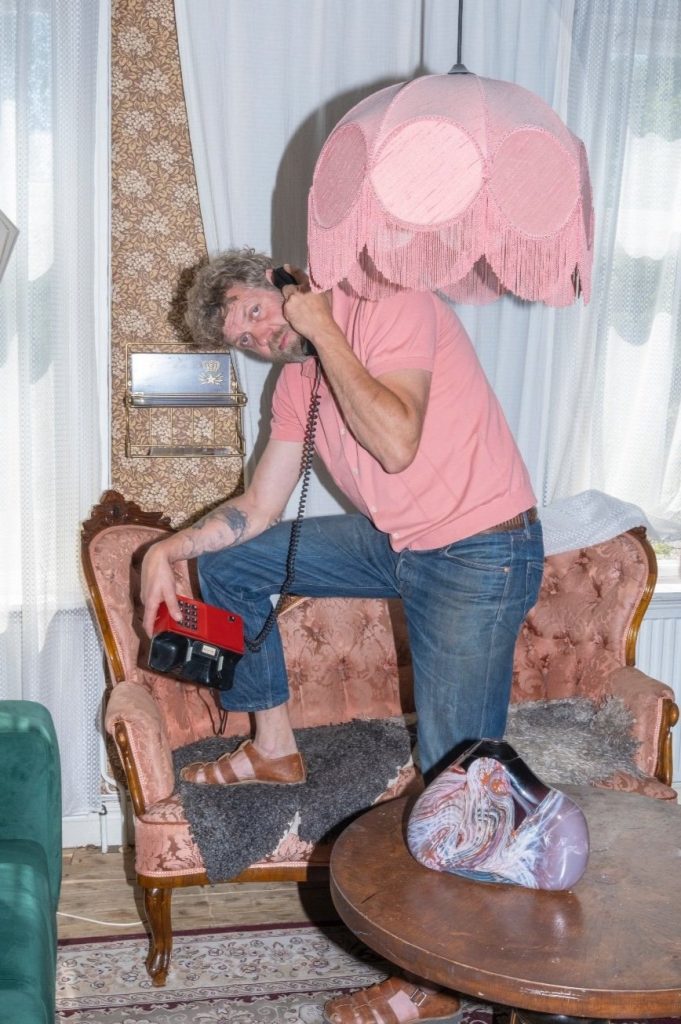

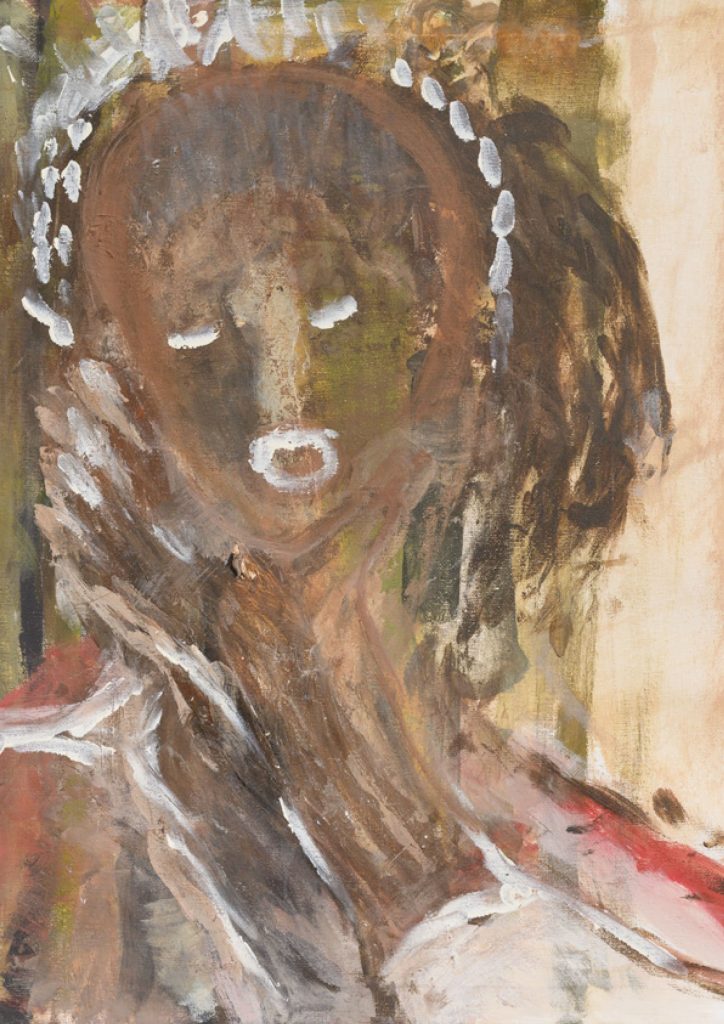

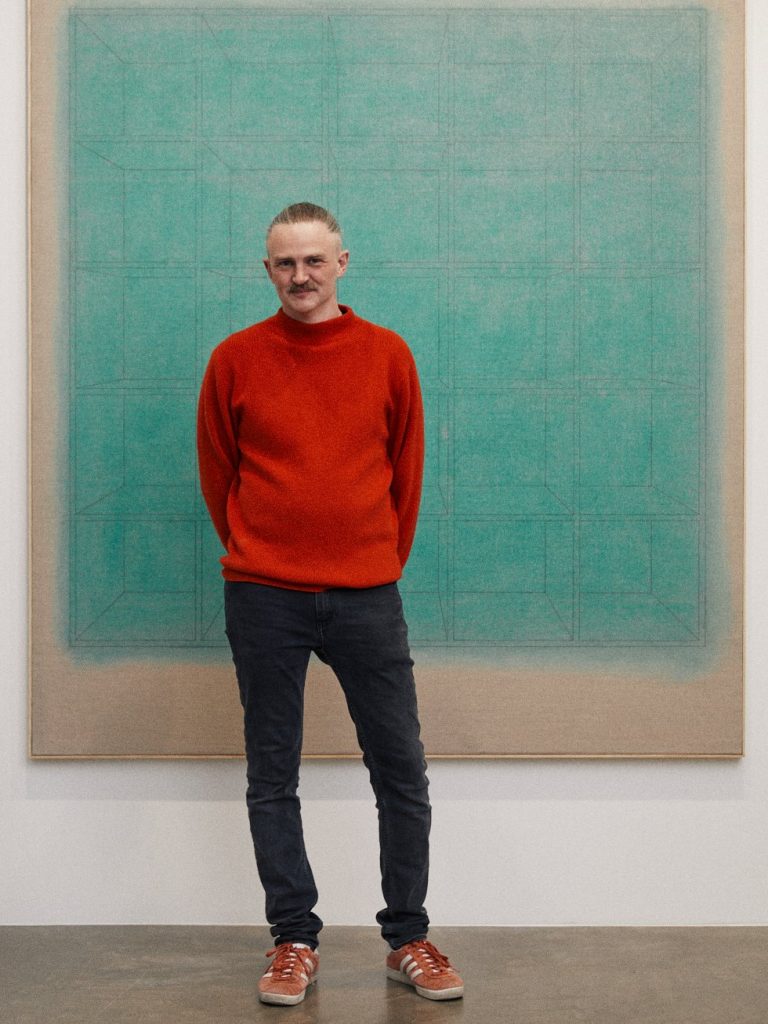

Leigh Bowery! Tate Modern Unveils a Bold Tribute to the Iconic Performer text Maya Avram Earlier this week, swarms of press flooded Tate Modern’s third floor, excitedly assembled for the preview of the museum’s latest exhibition, Leigh Bowery! Chronicling the late performer’s artistic practice in 80s and 90s London, it brings to the fore Bowery’s undeniable influence on pop culture as we know it today. “As an artist, he embodies much of what Tate Modern exists for, really; performance, reinvention, experimentation — in short, reimagining ways of seeing the world,” said Karin Hindsbo, Director of Tate Modern, as we embarked on a tour of the curated space. Closely entwined with London’s underground scene, Bowery has famously harnessed hedonism and subversion to challenge the banal. A performer, dancer, model, TV personality, fashion designer and musician, his provocative performance art was designed as a form of activism, encouraging people to push boundaries and encourage their reflection on life. The show space’s layout emulates Bowery’s chronological journey into the public eye, with each room symbolising a different part of the making of his persona. And so, the first room marks “the home”, the safe place where he (and his friends) assumed their character. It features some of his first-ever fashion designs, including gimp-inspired head masks, and other iconic motifs such as his synonymous polka-dot print. Dick Jewell Still from What’s Your Reaction to the Show 1988 © Dick Jewell. Then you step into “the club,” the gritty setting where his eccentric appearance became an aesthetic that urged onlookers to question the why and how they live. Set against the backdrop of Thatcher’s England, Bowery’s rebellion against conformity peaked with the opening of his club Taboo in 1985. The exhibition displays more than 20 of the intricate costumes he designed and hand-crafted, many with collaborator Nicola Rainbird and corsetier Mr Pearl. Bowery’s close friendship with renowned artist Lucian Freud marked a turning point in the former’s relationship with the contemporary art world. Now a subject in his own right, Bowery was depicted by Freud in the nude, bare of all embellishments to offer a fresh view of this flamboyant performer. This was a natural evolution of Bowery’s use of his body as raw material, notably stating that “flesh is the most fabulous fabric.” The exhibition culminates with Bowery’s foray into music with his band Minty. Uniting his love of performance, shock value and humour, it enabled him to push the limits of the human form while reimagining ideas around gender and drag culture. Bowery’s final performance at London’s Freedom Café in November 1994 was attended by long-term collaborator Lucian Freuda and a young Alexander McQueen, revealing how far-reaching his influence extended in the worlds of art and fashion. “I cannot think of a better way to launch our 25th anniversary programme than with a celebration of Leigh Bowery,” concluded Hindsbo. We couldn’t agree more. Leigh Bowery! Will run from 27 February to 31 August 2025, at Tate Modern, Bankside, London. Installation Photography © Tate Photography (Larina Annora Fernandes) Costume Photography 2024 © Tate Photography. Courtesy Leigh Bowery Estate. Dave Swindells, Limelight: Leigh Bowery1987 © Dave Swindells. Dave Swindells, Daisy Chain at the FridgeJan ’88: Leigh and Nicola 1988 © Dave Swindells. Installation Photography © Tate Photography (Larina Annora Fernandes) Fergus Greer, Leigh BowerySession 1 Look 2 1988 © Fergus Greer.Courtesy Michael Hoppen Gallery. Fergus Greer, Leigh BowerySession 4 Look 19 August 1991© Fergus Greer.Courtesy Michael Hoppen Gallery. Fergus Greer, Leigh BowerySession 4 Look 17 August 1991© Fergus Greer.Courtesy Michael Hoppen Gallery. Fergus Greer, Leigh BowerySession 3 Look 14 August 1990© Fergus Greer.Courtesy Michael Hoppen Gallery. Fergus Greer, Leigh Bowery Session 8 Look 38 June 1994© Fergus Greer. Courtesy Michael Hoppen Gallery. Fergus Greer, Leigh Bowery Session 7 Look 37 June 1994© Fergus Greer. Courtesy Michael Hoppen Gallery. Installation Photography © Tate Photography (Larina Annora Fernandes) Chalres Atlas, Still from Mrs Peanut Visits New York1999 © Charles Atlas. Courtesy of the artistand Luhring Augustine, New York. Chalres Atlas, Still from Beacuse We Met1989 © Charles Atlas. Courtesy of the artistand Luhring Augustine, New York.