Breath of Life an Interview with Markus Åkesson

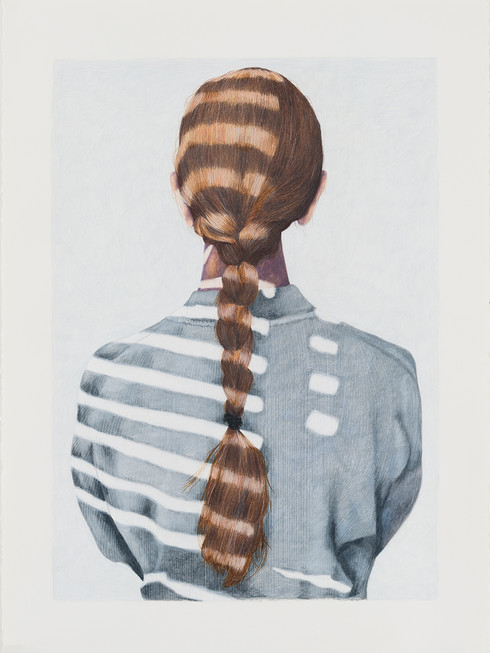

Breath of Life an Interview with Markus Åkesson text by Janae McIntosh “When I paint, I enter this world as an explorer and the painting process becomes a journey of discovery,” says Swedish artist Markus Åkesson. His artistic journey is steeped in myth and magic, serving as a portal to a world where reality and dreams intertwine, the familiar becomes uncanny, and beauty is tinged with an undercurrent of unease. From an early age, Åkesson had a passion for drawing and developed an interest in motif painting during his teenage years. His artistic talent was first nurtured in his initial career as a glass engraver, a craft that fed his interest in light and texture as well as shaping his meticulous attention to detail. Although Markus has no formal training in the evocative and technically sophisticated realistic painting that has come to define his work, he is deeply fascinated by patterns. He draws inspiration from pattern cultures around the world and creates his unique designs. Using a refined and surrealistic method, he skillfully integrates these patterns into his paintings. Drawing from a rich tapestry of influences, ranging from Old Master paintings and medieval symbolism to Scandinavian folklore and alchemical traditions, his pieces, whether they depict solitary figures suspended in time or taxidermied animals frozen mid-hunt, are imbued with quiet tension. His paintings and sculptures invite viewers into liminal spaces, where the boundaries between life and death, past and present, and the tangible and the imagined blur. Natalia Muntean: Your work often explores the boundary between reality and dreams. How do you navigate this boundary and how do you decide when a piece has successfully captured that tension?Marcus Åkesson: In my work, this liminal space between reality and dreams has always intrigued me. It is an “in-between” state, which reflects transitions such as the passage from childhood to adolescence or the moments between sleep and wakefulness. When I paint, I enter this world as an explorer and the painting process becomes a journey of discovery. I aim to create images that also allow the viewer to journey into this ambiguous space, perhaps offering a glimpse into another world. A piece has successfully captured this tension when it evokes a sense of mystery and invites personal interpretation. NM: You’ve described your art as a way to “create a world where I want to be.” Can you elaborate on what this world looks like for you, and how it evolves with each new piece?MÅ: I wouldn’t say that it’s one specific world, but rather that creation, or being in a creative process, allows any artist to explore ”other worlds”. This feeling of entering another space, or if we call it another world, forms a natural part of a creative process, which is intriguing and a big part of why I long to create. This also extends out to the physical workspace. My studio is more than just a place where I paint; it is an environment I have carefully curated, an attempt to a physical extension of the universe that exists within my paintings. It is important to me that my studio feels like a threshold, so when I come to the studio, I enter the space mentally as well. NM: Your paintings are known for their incredible detail and texture, such as the intricate patterns in textiles or the play of light on skin. How do you achieve such realism, and what challenges do you face in rendering these details?MÅ: Achieving realism in my work involves foremost meticulous attention to detail and the use of traditional painting techniques. My way of working with painting is centred around glazing; a traditional painting technique applied in realism, in which transparent layers of colours are applied over another thoroughly dried layer of opaque paint. However, when paying so much attention to details, one of the challenges becomes to maintain a balance between the complexity of the patterns and the overall harmony of the piece. All these details should enhance the narrative rather than overwhelm it. NM: You often work with oil paints because of their versatility and depth. What is it about this medium that resonates with you, and how does it help you achieve your artistic vision?MÅ: Oil paint’s versatility and depth have always resonated with me, allowing for a rich exploration of light, shadow, and texture. I usually work on several canvases at the same time, and they revolve in the atelier. Some are drying, while I add new layers to others. Oil painting’s slow drying time offers the flexibility to build layers and make adjustments continuously. NM: Your glass sculptures involve intricate techniques like glassblowing and gilding. How do you collaborate with master craftsmen, and how does this process shape the final piece?MÅ: Collaborating with master craftsmen is integral to my work with glass sculptures. The glass industry was once very strong in my region, and even though much production has moved abroad, the glass expertise is still very much alive. The skills in glassblowing and gilding of the craftsmen bring a level of precision and artistry that is crucial to realizing my ideas. It’s a collaborative process that allows for a fusion of artistic ideas and skills, resulting in pieces that embody both my artistic vision and the craftsmen’s technical mastery. It makes it possible to produce pieces that no artist could do alone because of the lifelong experience every technique requires, and that is fascinating. NM: Your piece ”The Room of Life and Death” has been widely discussed for its haunting beauty. What was the inspiration behind this work, and what do you hope viewers take away from it?MÅ: When I painted The Room of Life and Death, I was drawn to the moment when a child first begins to comprehend the existence of death, not as an abstract concept, but as something tangible, something inevitable. There is an unsettling beauty in that moment, a paradox I wanted to capture. The girl in the painting stands still, gazing at the frozen hunt before her, a fox lunging at a pheasant, its jaws wide