Aftermath of Paris Art Week 2025

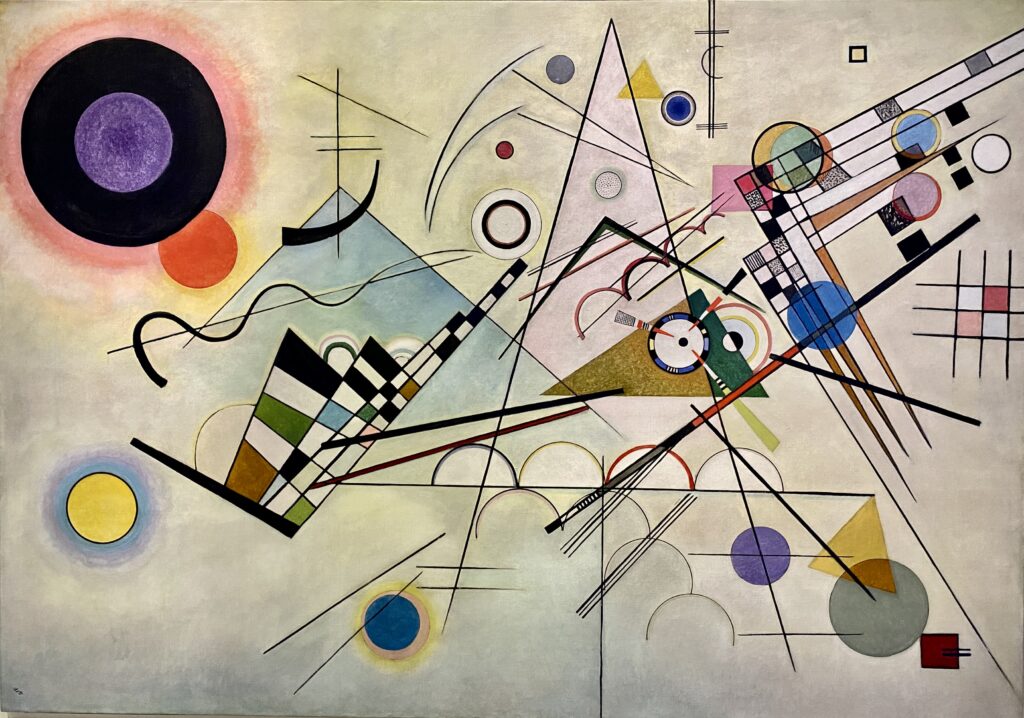

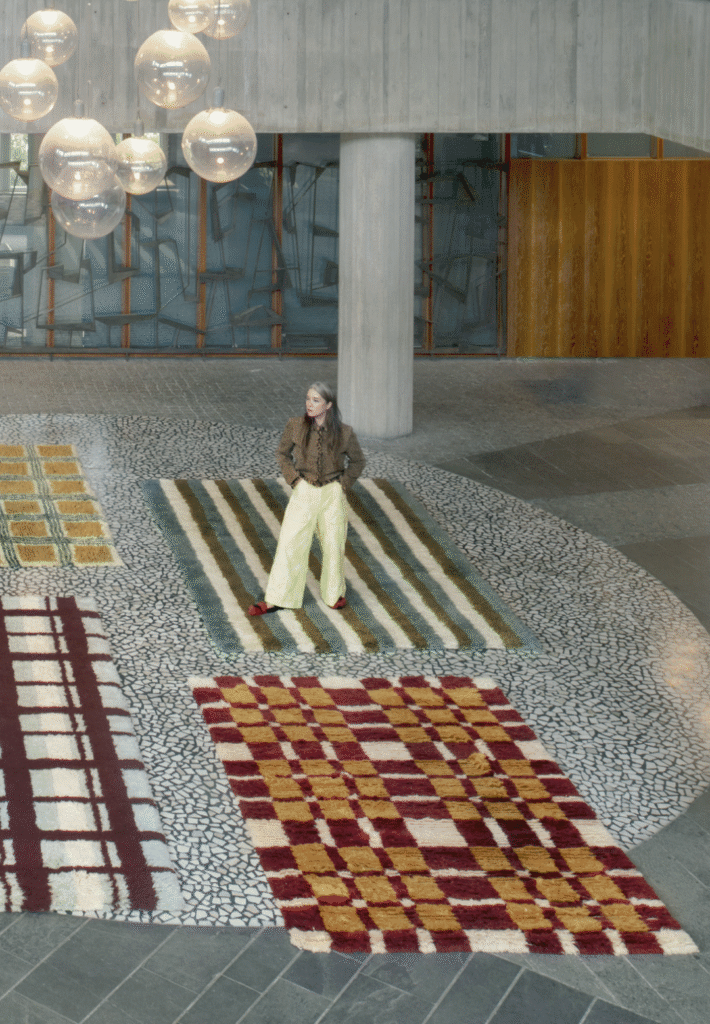

Aftermath of Paris Art Week 2025 – Echoes of Nature, Music, Human Interaction and Glass text Eva Drakenberg & Matilda Tjäder From «Exposition Générale». La Fondation Cartier pour l’art contemporain, 2 place du Palais-Royal, Paris. © Jean Nouvel / ADAGP, Paris, 2025. Photo © Martin Argyroglo. Open until 23 August 2026. Last month, the city of love gathered artists, enthusiasts, and collectors from all over the world, where Stockholm Art Week joined the rhythm of Paris Art Week. Looking back at the spectacular works experienced across galleries, foundations, and, of course, the ever-iconic Art Basel at the Grand Palais, we feel a sense of hope for the future. The exhibitions encouraged us to reflect on our relationship with nature and our behaviour in modern society, while allowing us to hold hands with the past when reality feels a bit too scary. Heading to Paris any time soon? Lucky you – many of the shows are still up and running. INTERDISCIPLINARY DIALOGUES Through a rich variety of expressions, we observed a recurring desire to explore the intersection of science and culture in our understanding of the natural world. By merging realms we often study in isolation, we are invited to embrace an interconnected, three-dimensional worldview. The reopening of the Cartier Foundation served as a symbol of this thematic shift, with its three-floor space fostering dialogue between architecture, nature, the act of making, and fiction. What happens when we begin to view matter through the dual lenses of emotion and logic? Likewise, at Art Basel inside the Grand Palais, many young artists echoed these conversations through a rich variety of perspectives. The Stockholm/Paris-based gallery Andrehn-Schiptjenko showcased Swedish artist Sally von Rosen, who elevates the spiritual dimension of material by emphasising the bronze sculpture’s own agency and emotion. Meanwhile, a visit to the Perrotin Gallery in the Marais showed The Sun Splitting Stones by the phenomenal India-based artist Bharti Kher, whose paintings and sculptures explore similar dialogues. We highly recommend visiting it. On the left: Sally von Rosen. « Motherform ». Installation view Andréhn-Schiptjenko Art Basel Paris 2025. Courtesy of the Artists and Andréhn-Schiptjenko © Joe Clark. Exclusive for Stockholm Art Week. From Bharti Kher. « The sun splitting stones ». Photo: Tanguy Beurdeley. ©Bharti Kher / ADAGP, Paris, 2025. Courtesy of the artist and Perrotin. Open until December 20th. SOUNDS OF MUSIC The city of Paris is known for effortlessly merging art forms, which we saw in the interplay between visual art and music. We were delighted to see the Philharmonie de Paris and Centre Pompidou join forces to produce the astounding Kandinsky exhibition La musique des couleurs. Visitors are invited to explore Kandinsky’s impressive collection of over 200 works, highlighting the spirituality of colour while listening to his musical references, from Wagner to Schoenberg. Incorporating piano notes was also recently explored more abstractly at the Marais gallery Chantal Crousel, with Mexican artist Gabriel Orozco’s solo exhibition Partituras. In other words, for a music lover, the art scene in Paris may feel especially exciting right now. From Philharmonie de Paris. « Kandinsky ». La musique des couleurs. » Own photo. Open until February 2nd 2026. From Gabriel Orozco. « Partituras ». Courtoisie de l’artiste et de la Galerie Chantal Crousel, Paris. | Courtesy of the artist and Galerie Chantal Crousel, Paris. Photo: Jiayun Deng — Galerie Chantal Crousel . From Elmgreen & Dragset. Massimodecarlo Gallery. Exclusive for Art Week 2025. Photo © Thomas Lannes courtesy MASSIMODECARLO. Exclusive for Stockholm Art Week. INTERACTIVE ART Interactive art stood out as a truly wholesome observation during the week, with several exhibitions revealing something intimate about our own everyday behaviour. Overall, we felt a renewed appreciation for the arts’ ability to create spaces for self-reflection and to question our individual roles within the collective society. A favourite of ours was the hyperrealistic sleeping sculpture showcased in the Massimodecarlo gallery window, created by the dynamic Scandinavian duo Elmgreen & Dragset. When we first passed the Marais gallery, we gasped, thinking it was an overworked or perhaps even a little over-partied gallerist. Trying to wake her up, we finally found ourselves laughing with other confused Parisians. It made us reflect on civil courage, the complexities of today’s gallery scene, and the delicate balance of everyday work life. Similarly, the iconic École des Beaux-Arts de Paris presented an interactive experience with its Objects Trouvés installation by Harry Nuriev. Visitors were invited to bring a personal object from home and exchange it for something new within the grandiose Chapelle des Petits-Augustins. The installation prompted reflection on how deeply personal materialism can be, even when it often feels homogeneous. After all, we are each drawn to different objects shaped by our own memories and personalities. From Harry Nuriev, « Objets Trouvés », Les Beaux-Arts Paris. Own photo. Exclusive for Stockholm Art Week. BLURRY MEMORIES Speaking of memories, we saw exhibitions that explored the complex theme through both abstraction and objects. At Foundation Louis Vuitton, we were blown away by the Gerhald Richter exhibition showcasing an exceptional retrospective of 275 works stretching from 1962 to 2024. Known for his blurring technique on photo-inspired oil canvases, we are reminded of the uncertainty of our collective memory. While at the Swedish Institute, Tarik Kiswanson explores memory through the language of objects. Instead of resolving historical contradictions, he exposes them and their lasting impact. From Fondation Louis Vuitton. Gerhard Richter. Own photo. Open until March 2nd 2026. From Institut Suédois. Tarik Kiswanson. « The Relief ». (Steinway Victory Vertical, 1944), 2025. Courtesy of the artist and Sfeir-Semler Gallery. Photo: Edward Greiner. Open until January 11th 2026. GLASSMANIA Strong. Fragile. Poetic. Glass as a medium of expression is becoming increasingly popular to exhibit, introducing a deeply personal dimension to an artist’s creative expression. Unlike working with other materials, glass is literally on fire, requiring high control and trust among collaborators. During Art Basel, in a setting like the Grand Palais, gleaming glassworks were instantly eye-catching beneath the iconic roof. Outside Grand Palais,