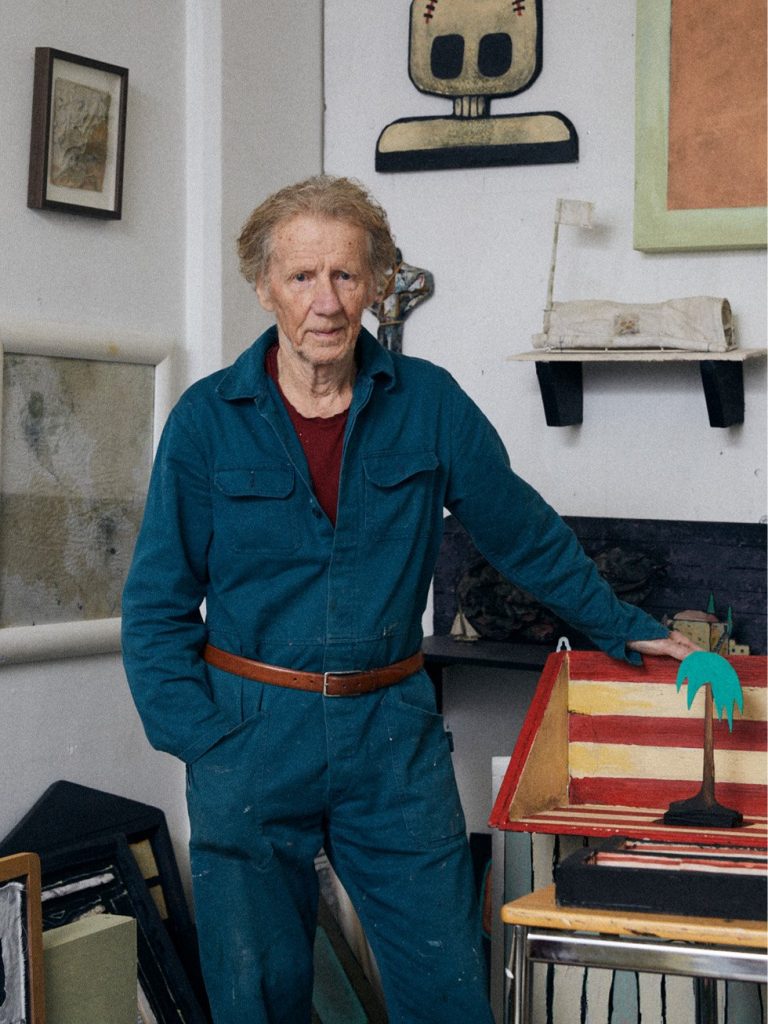

An Interview With the Artist Jan Håfström text Astrid Birnbaum Photograpy Sandra Myhrberg Jan Håfström stands as a towering figure in Swedish contemporary art, celebrated for his multifaceted contributions that have left an imprint on the nation’s artistic landscape. Born in Stockholm in 1937, Håfström’s artistic journey has been marked by a profound exploration of language, symbols, and a seamless fusion of diverse artistic disciplines. His recurring theme is the presence of death in life. Influenced by the movements such as minimalism and pop, Håfström’s artworks become a captivating synthesis of visual and conceptual elements. His canvases breathe life into a unique tapestry, where symbolism and storytelling intertwine to create distinctive narratives. They invite viewers into a realm of contemplation and interpretation.We met in his studio in Liljeholmen, Stockholm. Draped in a painter’s overall, Jan guided me through a collection of both new and old works that punctuated the studio space. Amidst the canvases and creative chaos, our conversation unfolded over coffee, providing a glimpse into the labyrinth of his mind. We finally got lost. Astrid Birnbaum: Jan, you were born in Stockholm and you studied philosophy at Lund University, followed by artistic studies at the Royal Institute of Art in Stockholm. How were your years in art school?Jan Håfström: Yes, it was after finishing high school in Gothenburg that I ended up in Lund, where I studied philosophy. I had heard that they had excellent lecturers there. There was a guy named Carl Fehrman who had written a book called “The Poet and Death” – so of course, I had to go there straight away! Before that, since childhood, I had been drawing, but that I would become an artist wasn’t so clear. However, I felt that the academic world wasn’t quite for me, so after moving back to Stockholm, I applied to the Royal Institute of Art. I suspected that being an artist was a way of life – independent, creating your own agenda, no one to boss you around. That appealed to me. There were groups outside art school that interested me. The magazine “Kris,” was run by people I spent time with, including my friend Håkan Rehnberg. Håkan and I met at the Royal Institute of Art. People at the school were theoretically quite boring, so we mostly socialised outside school. When I went to New York in the mid 70’s , Håkan –who is a painter –came along. A.B: New York, what does it mean to you? Which artists from your time there have inspired you? J.H: It’s hard to beat Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns. We lived on Church Street, just below Canal Street. Everyone gathered in New York. Landing there in the mid-’70s was a gift, especially when PS1 had just started – a lot was happening. An artist I was particularly interested in was Robert Ryman. He did incredibly simple things, just swiping the brush across the canvas. He taught me a lot. I got a studio at PS1 in the spring of 1977. The exhibitions there were crucial for me. “Montezuma’s Breakfast” by Richard Nonaswas one of them. It featured logs on the floor, moving in and out of rooms, creating a strange sculpture. Barnett Newman, the painter and sculptor, was also very interesting to us. We never met him; he died in 1970. But we were invited to his widow Anna-Lee Newman’s home, where she showed us the bed he had slept in the day before he left and never returned. It’s almost macabre – she preserved the bed exactly as it was. A.B: Would you say that your art draws much inspiration from your childhood?J.H: Yes. My dad was religiously inclined and wanted me to attend Sunday school. In Örebro, there was a Sunday school in Immanuel Church, an independent church. They were crucial. Their teaching for children around my age, about 5 to 6 years old, involved a big box with sand where we moved around small sculptures, replaying religious themes. Much in my art comes from that time, and from there I’ve incorporated the theatrical aspects. A.B: Certain authors like Joseph Conrad and Edgar Allan Poe seem to be recurring in your works. What is it that interests you in their work?J.H: They scared me a bit, perhaps, which I found interesting. Embracing them makes the reading experience extreme. Both Poe and Conrad attempt to delve into some kind of darkness, into a realm of death from . One enters but does one ever come back the same? A.B: References to death are often present in your art. Can you share your thoughts on this? Do you often contemplate death?J.H: My dad talked a lot about death. He was a bit narrow-minded, I think. But he introduced me to Edgar Allen Poe! With all the difficult things happening in the world now – in Ukraine and with wars worldwide – certain thoughts come back. I’ve thought a lot about why I return to death in my art, but I believe that by creating what I do, I find a way to process what’s happening. I have to survive mentally; otherwise I might go crazy. A.B: Last year, you released a collection with the fashion brand A Day’s March, featuring coats inspired by one of your famous works – Mr. Walker. The statue at Central Station is named “Who is Mr. Walker?” Do you have an answer to that question?J.H: Oh, that coat… Fabric and clothes have played a big role in my art. And who is Mr. Walker? I get the answer from people around me. The other day, I was on the subway, and I noticed a man staring intensely at me. Eventually, he approached and said, “I would like to thank you for the sculpture at Central Station. I go there sometimes and wash my soul.” For me, Sunday school and Jesus are still present – and they are connected to Mr Walker from the comic strip Fantomen – the Phantom. There are parallels between