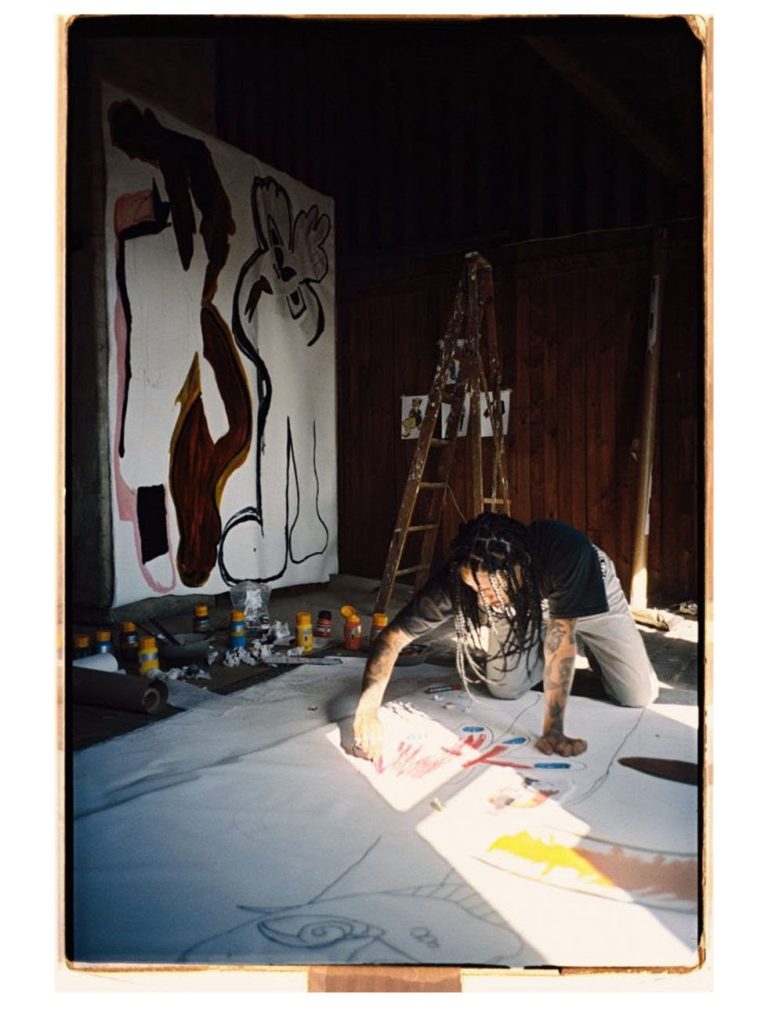

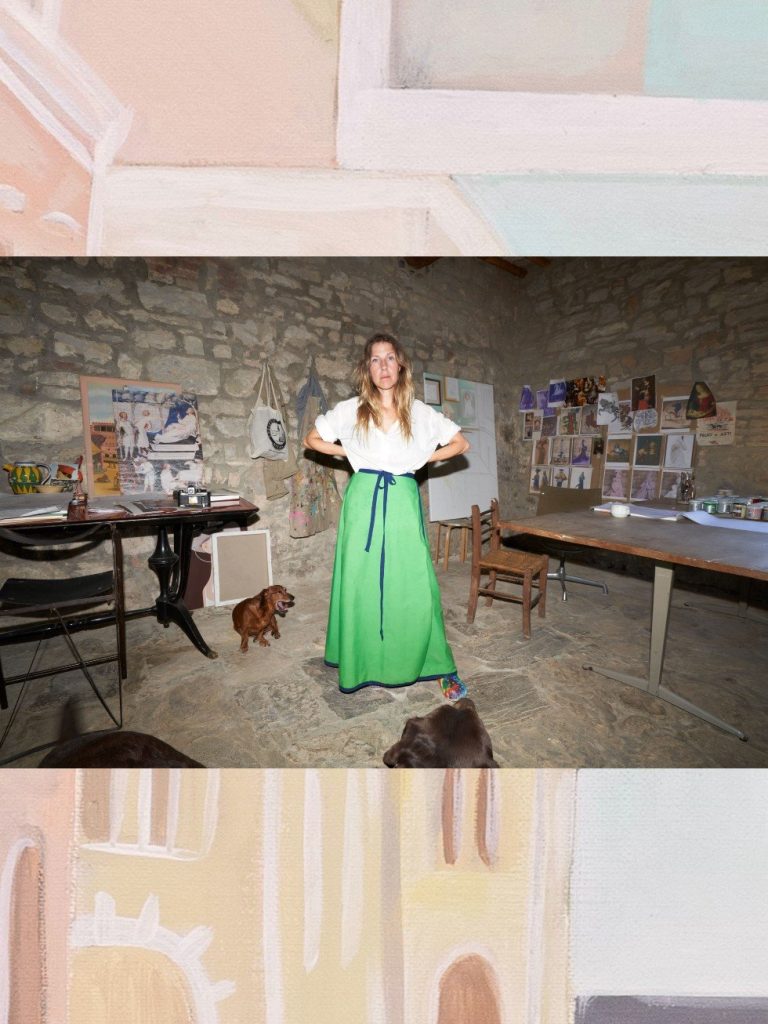

Everything I Do, Every Step I Take, Has to Be Connected to Reality. A Conversation With Ylva Snöfrid. text Astrid Birnbaum Photography Sandra Myhrberg Known for her innovative blend of painting and performance, Ylva Snöfrid has captivated audiences worldwide with her unique exploration of existential themes. Her works are deeply introspective, often drawing on historical motifs to delve into the human experience. Her current exhibition, part of the Cosmos Vanitas series, is titled Jungfraujoch – High Altitude Paintings and is showcased at CFHILL in Stockholm. It takes us to Jungfraujoch, the second-highest viewing point in Europe, where Snöfrid’s artistry melds with the breathtaking elevation. The resulting celestial maps chart the intimate terrains of human existence. Central to Ylva’s work is the theme of ‘Vanitas’, reflecting on life’s transience. Her paintings don’t just depict this; they embody it, with each brushstroke and colour choice resonating with the vibrancy of life amidst change. Ylva, I would like to begin at the beginning. Looking back, what first inspired you to pursue a career in art?I think I understood very early that I was an artist. My parents were also making art, even though they had ordinary jobs. They lived like artists. Even though my childhood was a struggle in many ways, they were very supportive of me making things. There are specific moments from my childhood when I realized I was an artist. One was when I was around six and I made some drawings of the queen from Elsa Beskow’s Midsummer tale. The queen was helping the wild weeds and the flowers to get together to have a party. The tale is about a girl who falls asleep and sees the world of these plants. I tried to make a portrait of her, but I couldn’t manage to draw her like Elsa Beskow. I was so disappointed with myself. It was such a struggle, and I could not stop. It was more important than many other things in my life at that moment. Part of my life as an artist began during my childhood. I had a mirror twin who lived behind the mirrors, named Snöfrid, while I was Ylva. I wrote a poem about her as a child, and she gradually became more real, embodying my artwork. Once, I created her as an alcoholic beverage that I distilled on paintings for an installation, inviting people to ‘drink’ her. During interviews, she accompanied me and even answered questions. Consequently, some interviews featured Ylva, Snöfrid, and the interviewer. Unable to rid myself of her presence, I eventually created a life-sized doll with my proportions. When my family and I moved to Athens, I felt the need to take the next step in my artistic practice, necessitating a transmutation. This eight-hour ritual, performed through a mirror, was part of a show in Montpellier curated by Nicolas Bourriaud. I sat on paintings, inviting the audience to participate. In a small tent, I conducted the actual ritual, meeting Snöfrid in the mirror. I painted my vagina on small paintings and invited people to sit down, serving her—us—on these paintings. Through this process, I abandoned my surname and became Ylva Snöfrid, uniting us as one. We are now physically connected all the time. I wear gold joints—gold jewellery around my waist, wrists, neck, and fingers—gradually covering my entire body. These joints symbolize our connection and frequently appear in my paintings. The use of gold has multiple reasons. In my childhood, within an anthroposophic environment, I received gold injections to strengthen my sense of self and create a boundary between the outer and inner worlds. I administered these injections myself into my belly. Your current exhibition, ‘Jungfraujoch – High Altitude Paintings,’ shown at CFHILL, takes us to the heights of the Swiss Alps. What drew you to this remote location?In my artistic practice, I have always worked with my own life and body as the foundation for my artwork. My approach is highly subjective and intuitive, building on my personal experiences. I have explored themes from my own childhood to motherhood, including significant events like giving birth. For instance, my father was a heroin addict during my childhood, and this profoundly influenced my paintings and overall artistic practice. For me, art must be as real and tangible as the ordinary reality I perceive. In the five years before starting the project that culminated in this exhibition, I lived in Athens with my family. In Athens, I created a secluded artwork that was essentially a home, complete with furniture and paintings. We slept on paintings, we ate on paintings. This immersive experience prompted me to look beyond the confines of this project and explore the external world in a more existential manner, recognizing that I live on Earth, a planet that offers a broader, planetary experience. This exploration extended to the cosmos and my connection to the world on a larger scale. As part of this study, I created three monumental paintings, “Cosmos and Vanitas,” each 7×6 meters high, which are installed in Lund. This project involved visiting various places to explore the connection between mass and atmosphere. My husband, Rodrigo, discovered the Jungfraujoch research station, situated at an altitude of 3,500 meters. It is one of the highest research stations globally, attracting researchers from around the world. Rodrigo applied on my behalf for the opportunity to stay there. Therefore, I went up this high mountain. How did the environment of Jungfraujoch affect your creative process?I went there thinking I was going to do a study on the atmosphere and mass. But I didn’t really think that it could affect me physically. When I arrived, a whole other process started within myself, inside my body. The first thing I felt was this very high pressure on my brain. Later, my eyesight improved dramatically because my eyeballs actually adjusted to the pressure. I felt very bad physically. I started to get high altitude sickness, and I was just in that feeling somehow. I got worse and worse, hour by