Karla Black on material, chaos and the function of art

text Natalia Muntean

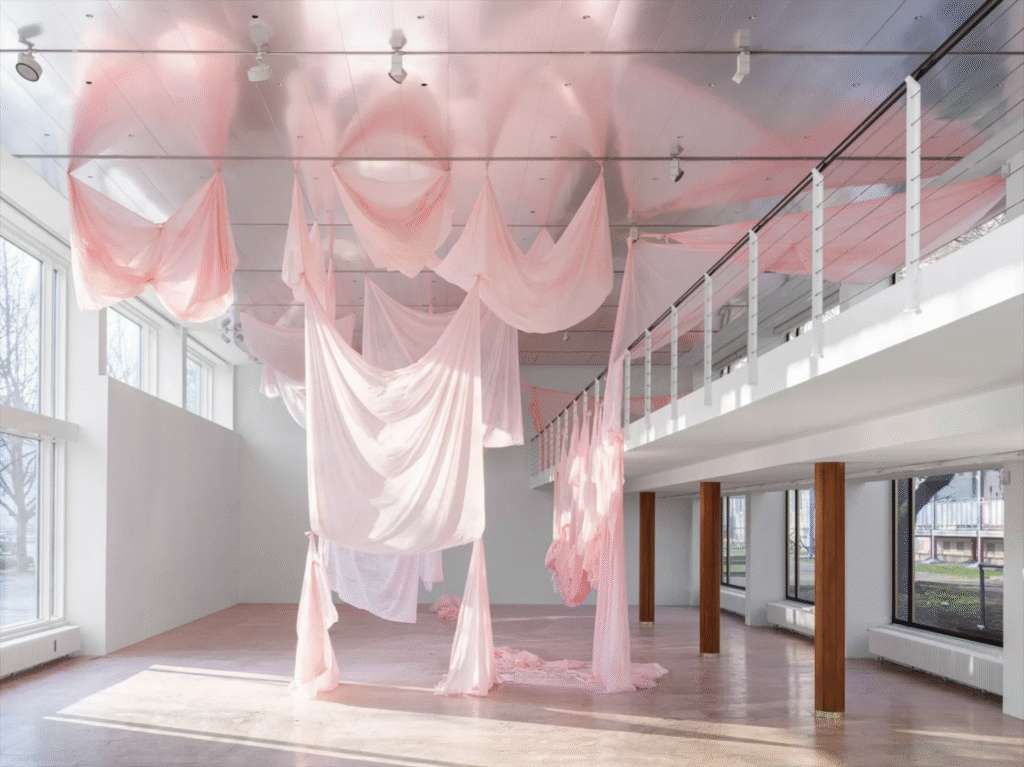

“For me, culture is no different from nature; there is no hierarchy,” says Glasgow-based artist Karla Black. Known for her fragile, pastel-coloured installations made from materials like plaster, cellophane and makeup, Black has long explored the physical and emotional charge of matter itself. A Turner Prize nominee and Scotland’s representative at the Venice Biennale in 2011, she continues with her current show at Belenius Gallery in Stockholm to blur the line between painting and sculpture, insisting, as she puts it, on “the difficult, messy, chaotic characteristic of human behaviour” that keeps art alive.

Natalia Muntean: Your work often resists explanation in words. When you begin preparing for an exhibition, where do you start? With a material, a colour, or with the space itself?

Karla Black: The first thing that happens is that a desire arises in me. Maybe I want to mix paint into a particular colour, or touch a certain material like polythene, or scrabble around with some powder. In this sense, I think that my work begins with an exercising of the unconscious, which is experimental.

NM: You have described your sculptures as having “functions” rather than “meanings.” In the context of the Belenius Gallery show, what kind of functions or consequences do you hope these works might have for visitors?

KB: The ambition that I have for my work in general – to force the institution or the gallery to present what art really is – the difficult, messy, chaotic characteristic of human behaviour that is so necessary to allow and to preserve. I hope that my work practically accomplishes something – it forces what art really is into the arena of the gallery and of the historical canon, something that has been very much missing in recent times, as art fairs and commercial galleries and therefore, the prominence of the transferable object has so prevailed. I want to make the real thing, not just some sort of dead historical, immovable object. It should also be ‘difficult’ to move around the powder without damaging it, and to encounter the possible stickiness of the vaseline, etc, I hope people feel this.

NM: Pastel colours play a central role in your installations. How do you think their softness shapes the atmosphere of this exhibition?

KB: I use colour like I use form. In a way, colour is a material for me. It is really the tone of the colour that is important. Just like the sculptures are almost objects or only just objects, so the colour is only just colour. I never use primary colours because I am mostly trying to get as close to nothing as possible, or as close to white as possible.

NM: Each of your exhibitions carries only your name as its title. What does it mean for you to strip away all other framing and let the work stand on its own?

KB: It’s a feminist stance. It is also a statement about the importance of abstraction. The ‘great name’ of the artist, as used in museum shows and monographs, is traditionally of male artists. The name itself as title is a representation of the fact that the interaction of me and the space is all there really is.

NM: When you step into the finished space at Belenius, what do you feel the works are doing here?

KB: Hopefully, they are embodying a ‘real’ creative moment in an increasingly hermetic, sealed-off, commercially driven art world that prizes the transferable object above all. Hopefully, they don’t appear too ‘finished’ or ‘clean’ and they are therefore allowing space for the process, for the mess to be felt by people in the pristine gallery space itself.

NM: What is the most recent material, colour, or gesture that truly surprised you in your own work?

KB: The use of the mirrors is a surprise to me. I never really expected to work on a surface that is attached to a wall. There was always mark-making on my sculptures, and there was an aspect of the sculptures that kept getting thinner and thinner. Although it is a surprise, it also feels like a natural progression. I think I can only make works on 2-dimensional surfaces if those surfaces are either reflective or transparent because, somehow, the work still needs to involve space or the 3-dimensional.

NM: Do you see your work as more about exploring the world, or about creating a space separate from it?

KB: Both, I suppose. The world is the world. I think my work is part of nature. For me, culture is no different from nature; there is no hierarchy.

NM: What do you hope people take away from your show?

KB: An impetus towards physical response.