Gavin Gleeson’s Partial Parade Offers a Playful Pause

text Natalia Muntean

Gavin Gleeson found painting at twenty-seven. Or perhaps, painting found him. “I was in Paris, working a remote job, and I had taken a few drawing classes, but I just decided to pick up some paint for the first time and did a little watercolour. That was really the first time I painted,” he says. Born to Irish parents and raised in Kentucky, Gleeson grew up between worlds. “Growing up as a first-generation Irish American definitely gave me a sense of feeling a little bit abnormal,” he says.

What began as a peek into painting became a path of its own, leading him away from business and into an intuitive studio practice where, he explains, “I like coming into the studio as if it’s an improvisation session.” He never imagined it would carry him as far as a master’s degree at the Royal College of Art. Now presenting his first solo exhibition, Partial Parade, at Saskia Neuman Gallery in Stockholm, Gleeson translates how he experiences the world into canvases, inviting the viewer to join him in a “playful pause.”

Muntean Natalia: You picked up a brush at 27, and at 30, you have your first exhibition?

Gavin Gleeson: I’m pinching myself, definitely! Growing up, my next-door neighbour was a lawyer by day but painted in his spare time. I would see him paint or make sculptures, so I was aware of it, but I didn’t think anybody painted full-time.

NM: But was there something that made you pick up the brush?

GG: Honestly, boredom. I wouldn’t start work until the afternoon and just wanted something to do, so I signed up for a class. Later, back in Ireland, I reached out to a second cousin who’s a painter. He told me what to buy, a few basic colours, and I started painting in my Nana’s garage, using old bottles and family photos as references.

Eventually, I found a one-year course at the Burren College of Art, a tiny village on Ireland’s West Coast. When 250 Ukrainian refugees moved in during the war, the population doubled overnight. I would drive past the playground, the kids playing, the women smoking, against this bleak, windy landscape. That contrast between playfulness and heaviness really stuck with me. There was also a Ukrainian artist at the school, in his seventies. We would talk through Google Translate. His work filled whole walls – huge pieces. Even without understanding the words, I could feel the weight of them. It taught me that emotion can be grasped through marks and strokes alone.

NM: Let’s talk about your show, Partial Parade – what does this moment mean for you? And how did you land on that title?

GG: It’s very exciting because I waited so long to get started. The show came together at a good time because it can be tough when you’re coming out of your master’s degree, a bit aimless, and you’re just making work to have a portfolio and get by. When it comes to the title, it came from its dual meaning – partial as in incomplete, and partial as in biased. It felt cheeky. Is it a parade or a protest? I like that ambiguity. Humour is a big part of my Irish culture. It’s an invitation to improvise, to question. I ask myself, where am I being partial? Coming from business, from a place of privilege, there are a lot of questions we’re all facing.

NM: And does painting give you the answers?

GG: Maybe just better questions. A place of refuge and questioning. I think art’s inherently political. I think it’s a really important time for art and painting. For me, it’s a reflection of what’s going on. I feel proud to be a painter right now. I very much feel like a member of a choir more than someone trying to prove a point. And I think that’s really important to me: one of many.

NM: Do you have a routine? Is it like a nine-to-five for you?

GG: I wish. That’s the goal. It’s a balancing act in London. Initially, it was part-time jobs, jumping in the studio when I could. Now I work full-time and come in on weekends or an evening. I have the attention span of a puppy in the studio, which is good and bad. But with that excitement of, “Oh my god, there’s so much to paint,” it feels like I could keep going, which is a nice feeling. I’m quite a prolific painter. When I go to the studio, I get my painting clothes on and listen to music very loudly. There’s a getting stoked aspect, like getting psyched up for a game. It becomes like a spiritual practice, searching for truth from the unknown. My mantra is “trust the hands.” They’ll lead you where you need to go.

NM: What role does playfulness have in your process?

GG: Coming into the art world, I found it overwhelming with all the rules. Then you see a kid with a sketchpad just doing their own thing. My cousin, for example, has autism and is an amazing artist with no agenda. We had this moment of communication through art when we drew one of his cartoon characters. That was right before art school, and that started from play, as so many ideas do. Things get legs on their own.

NM: Who or what influences you the most?

GG: Music. My brother’s a musician, my dad works in music now, and my best friend back home is one too. When we were younger, he’d be looping tracks in one room while I drew in another; we would feed off each other’s energy. That rhythm and spontaneity are what I try to capture when I paint. Growing up in Kentucky also shaped me. There’s a strong punk and DIY culture there – that “just make it” attitude. It taught me not to wait for permission.

NM: Many of your works feel both playful and uneasy. How do you find that balance?

GG: Trial and error. I paint fast, and I make a lot. Sometimes I destroy paintings. Others I’ll paint over. There’s a fine line between playful and too much, and I’m still learning where it is. I think the heaviness comes from life, from paying attention to what’s happening around us. You can’t really separate it from the joy.

NM: Your works often include everyday objects like ladders. Are they specific memories, or are they functioning as symbols?

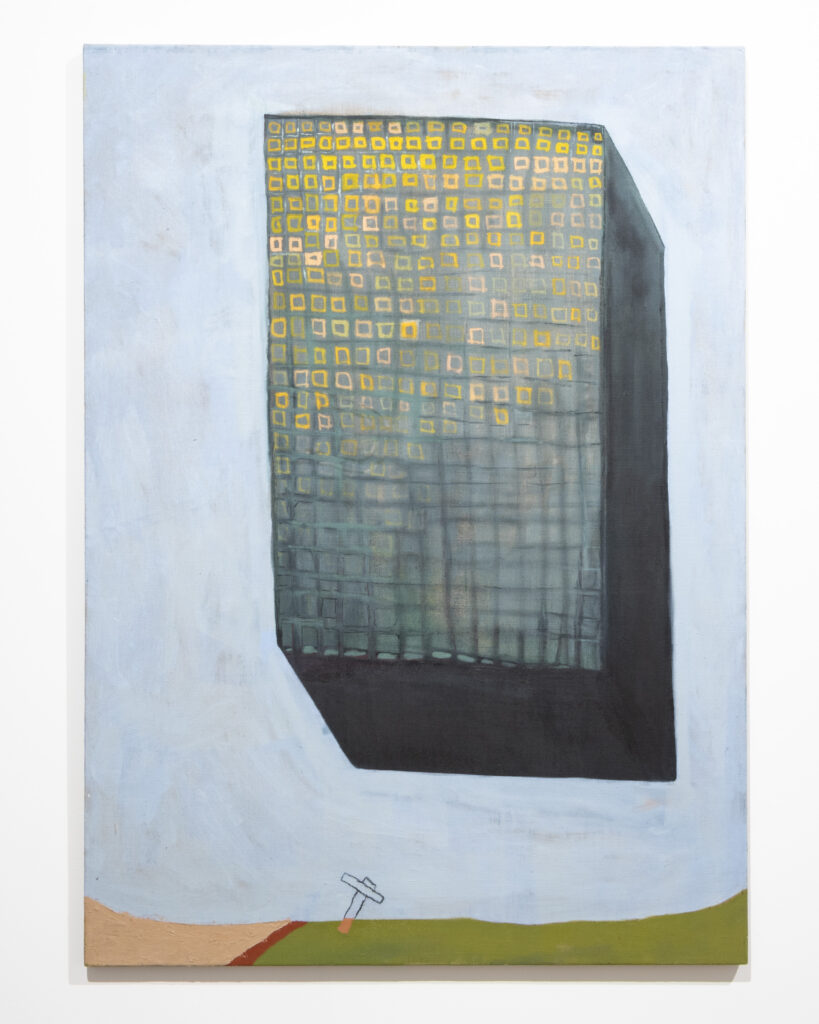

GG: They’ve started to emerge, things like shells and outlines. The ladders started as a simple drawing I made a couple of years ago. There’s also this hilarious thing to me – this tool that’s like ten thousand years old. I had this job in school where we had to do ladder training, and I thought it was funny. Here is this very basic device that is still quite dangerous to humans; we haven’t quite figured it out. But there are also a lot of connotations to it for such a simple thing – climbing the corporate ladder, the art world… Jacob’s ladder in the Bible, this guy who tried to make a ladder to climb all the way to heaven, if I connect it to my Catholic upbringing. There is a painting in this show called Too Far Jacob, and it’s just a little bit of a ladder sticking up and then a coffin or something.

NM: I’ve read that you title your works at the end – why is that? What role does that vocabulary and love of language play in completing the paintings?

GG: I really get a kick out of them. The title is where I start to understand a painting; it clicks into place and reveals the through line for me. Since the painting process is improvised, I title the works in batches afterwards. I approach titling with the same urgency as painting: don’t overthink it, just let the words come. If a clever title comes up early, I’ll sometimes scribble it next to the piece, and that helps me finish it. I think I’m a very verbal person, and I’m always trying to get better at painting – I think that’s why I like it so much, it’s a challenge. But I do think there’s a lot of power in words. For instance, there’s a painting in the show called Timorous Machination. I found those words by popping open a book of poems by the Irish poet Seamus Heaney. I looked up ‘timorous’, learned what it meant, and the title just worked. Painting is my new way of learning.

NM: What do you hope people take away from Partial Parade?

GG: I’ve been trying so hard to answer that question and hoping someone would give it to me. I hope there’s enough room in the paintings that they can be an opportunity for people to also get to improvise and to hold space where there isn’t a right or wrong answer, but to stay open. My works are weird, and I appreciate that. I end a painting when I feel there are more questions than answers, like an open-ended riddle. A lot is going on in the world, and I don’t try to avoid that. I try to hold it, wear it like a loose garment. I hope it’s an opportunity for people to have a different perspective. I love the sense of play, so maybe the show can be a playful pause.