The Art of Resistance: A Conversation with Carouschka Streijffert

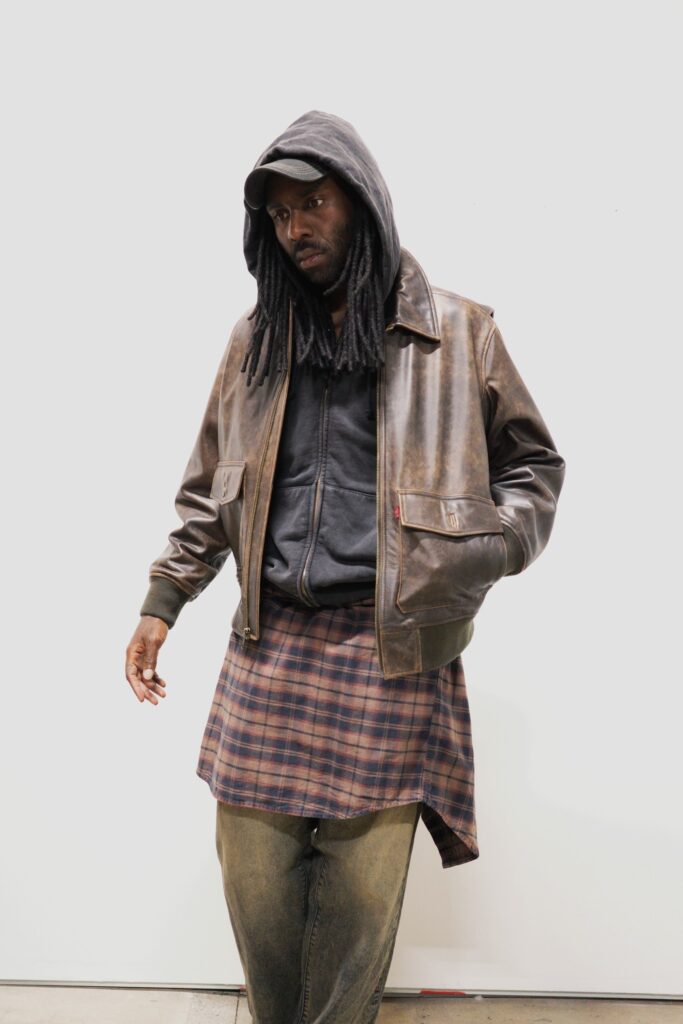

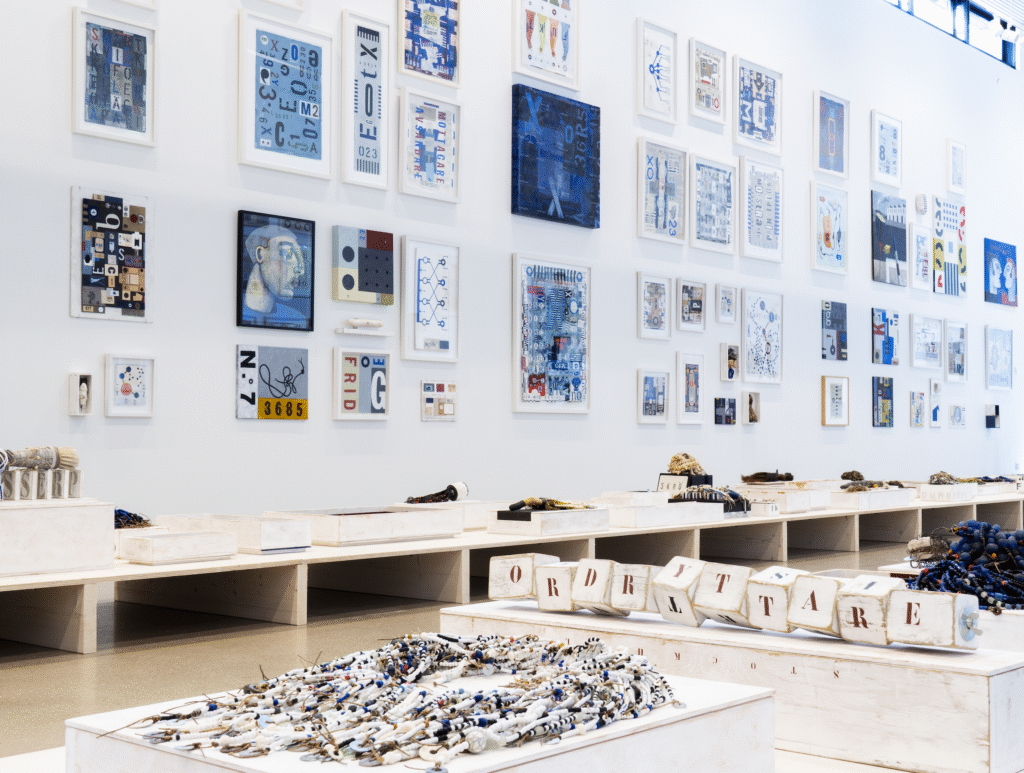

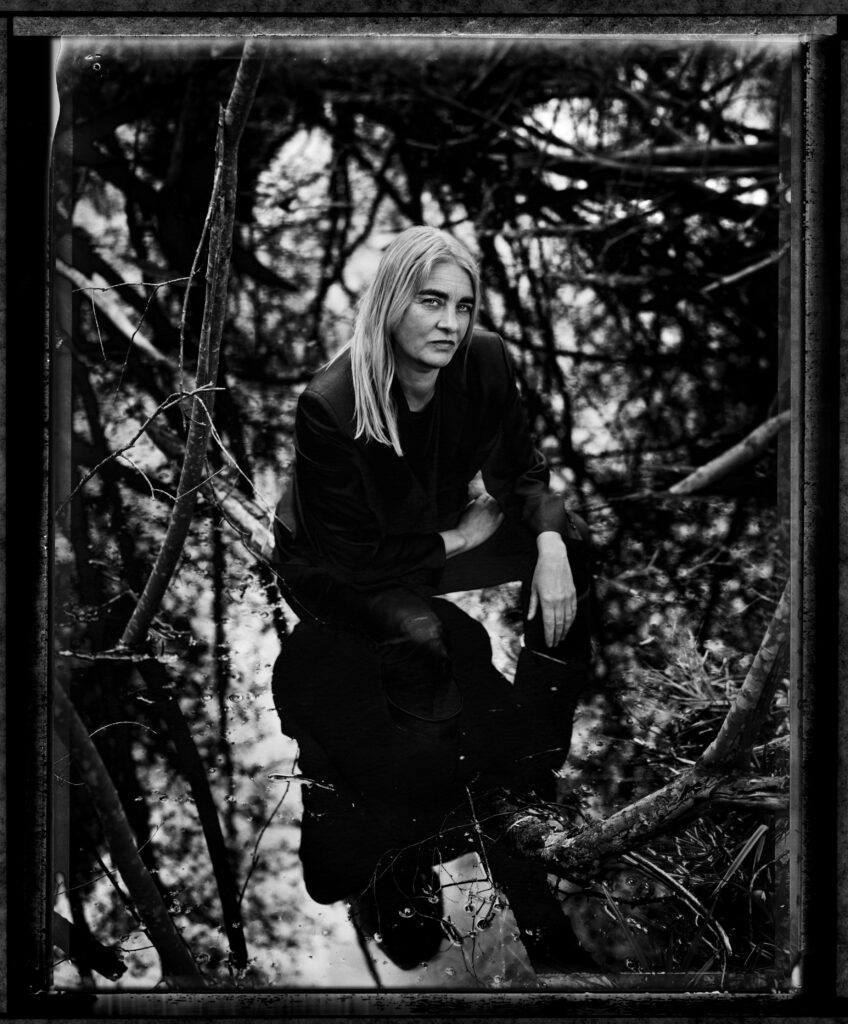

For over five decades, artist Carouschka Streijffert has made her mark within the Swedish art scene, working at the intersection of sculpture, architecture and scenography. In a world saturated with the new and the digital, Streijffert’s practice is a testament to the poetry of the discarded. She does not simply reuse materials; she listens to their history, taming cast-off fragments of metal, wood, and paper into objects, giving them new meaning. As Drivkraftens seger över motståndet (The Victory of Urge over Resistance) opens at RAVINEN Kulturhus, we talked to an artist for whom creation is a vital, almost philosophical act.

The exhibition is titled “The Victory of Urge over Resistance.” What does “resistance” mean to you in your creative process? Is it a physical property of the materials, a mental state, or both?

It is in the psychological resistance that creativity arises. It is in the friction, in the complexity, that the work grows, takes shape, is born, and comes into being. To eliminate resistance is to embrace laziness, and then the result becomes polite and empty. To create is presence – a driving force that shows direction. You are alive. You exist.

For over five decades, your work has centred on reclaimed and found objects. What is the “call” you feel from a discarded piece of metal, wood, or paper? What makes you know an object has a place in your art?

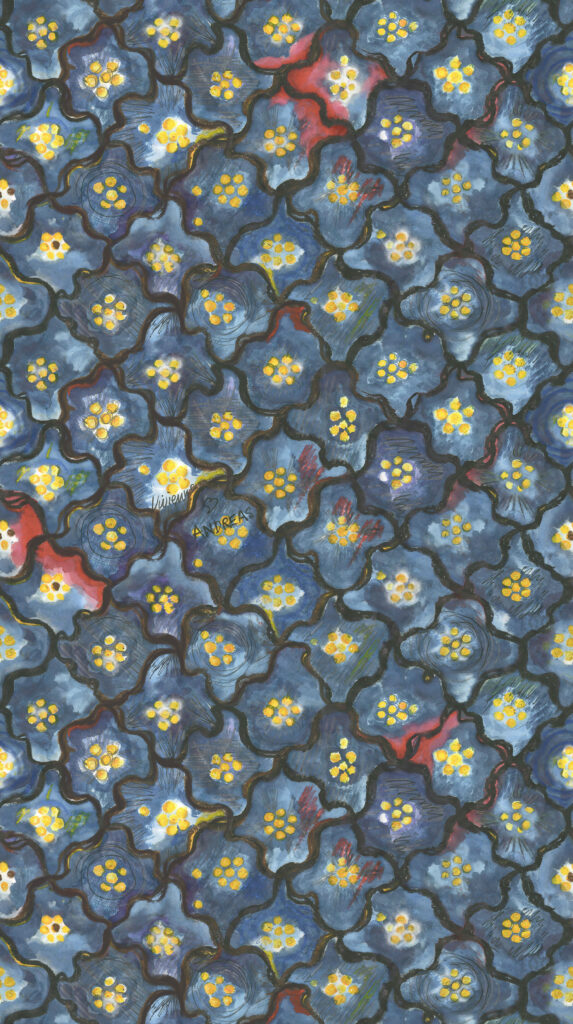

The world is flooded with used-up material, and it’s hard to ignore. I choose to see the possibilities in the discarded, details of beauty, regardless of the material’s properties. My aesthetic brings together the fragments, a dialogue between the hand and the gaze. The feeling of holding and weighing the discarded in my hands, of not wasting matter already charged with obscure experiences. I tame and shape the cast-off into an existence in the present. A collage. A sculptural object. The passion reflects my feelings, experiences, and memories.

Your practice spans art, architecture, and scenography. How does your thinking about space and environment influence the individual objects you create, and vice versa?

I create for the person who inhabits the spatial environment. It’s about proportions, the individual in the space. What is the room going to be used for? Here, function is the guiding factor. The financial framework, the size of the surfaces, and the amount of light entering. Is it a permanent room? A temporary room? A scenographic design has the task of framing or enhancing a drama. Scenography is meant to help the actor in the performance and give the viewer, the audience, a visual enhancement. Here, there are no boundaries. Architecture is a form of mathematics, logical analysis. The building, its function, reflects the volume of the rooms and how they interact with each other. The façade and the interior are in dialogue. The visual and functional expression of the materials should strengthen the human presence in the architectural space.

Your work is described as both “raw” and “precise.” How do you balance intuitive, raw expression with the technical skill and precision of a craftsperson?

A determined skill of interaction between my hands and a sharp eye. The visual must constantly speak to me. Analogue work has been performed by humanity since our beginnings. That talent must not be destroyed or erased. Intuition and skill arise and are maintained through constant practice, and then the difficult becomes a certainty of precision. The simple, bare, and obvious can be interpreted as rawness. Something that is not hidden or disguised by external cosmetics is automatically natural beauty, a form of truth that speaks to us.

Much of your work feels like a preservation of memory and history. Do you see yourself as an archivist of sorts, giving a new life to the fragments of our time?

Humour and playfulness are constantly connected to the seriousness of my artistry. Valuation and selection are continuously applied in my search for why and how to transform the urban waste into a new existence. This pursuit and stewardship are similar to an archivist’s logical sorting of the past. I house my finds in self-built archives, with a structure based on the qualities, colours, and properties of the materials. It is in these collections that I can repeatedly pick and replenish from the treasure trove of lost and found objects, year after year. The creation is endless. It becomes my own decay that will eventually bring a brutal end to the creativity of documentation.

In an age of mass production and digital saturation, why do you believe your analogue, hands-on approach feels so relevant and urgent to contemporary audiences?

The movements of the hand, the tempo, create reflection, not nostalgia, but trust. Craftsmanship requires time, a tactile substance. Not like our world’s clicking in front of glaring screens, where we are bombarded and slip off the rapid-fire impressions we rarely can avoid. This makes us blind and deaf to actual reality. Mass production and endless online shopping of unnecessary products will deteriorate our mental health and the Earth’s resources. Thousands of massive cargo ships float daily in our oceans, filled to the brim with newly manufactured “trash.” Why? Humanity has forgotten that the hand is our best tool. Working analogue today is not a retreat but a direction forward.