Between Surrealism, Memory and the Female Gaze - An Interview With Sanna Fried

text Elsa Chagot

photography Sandra Myhrberg

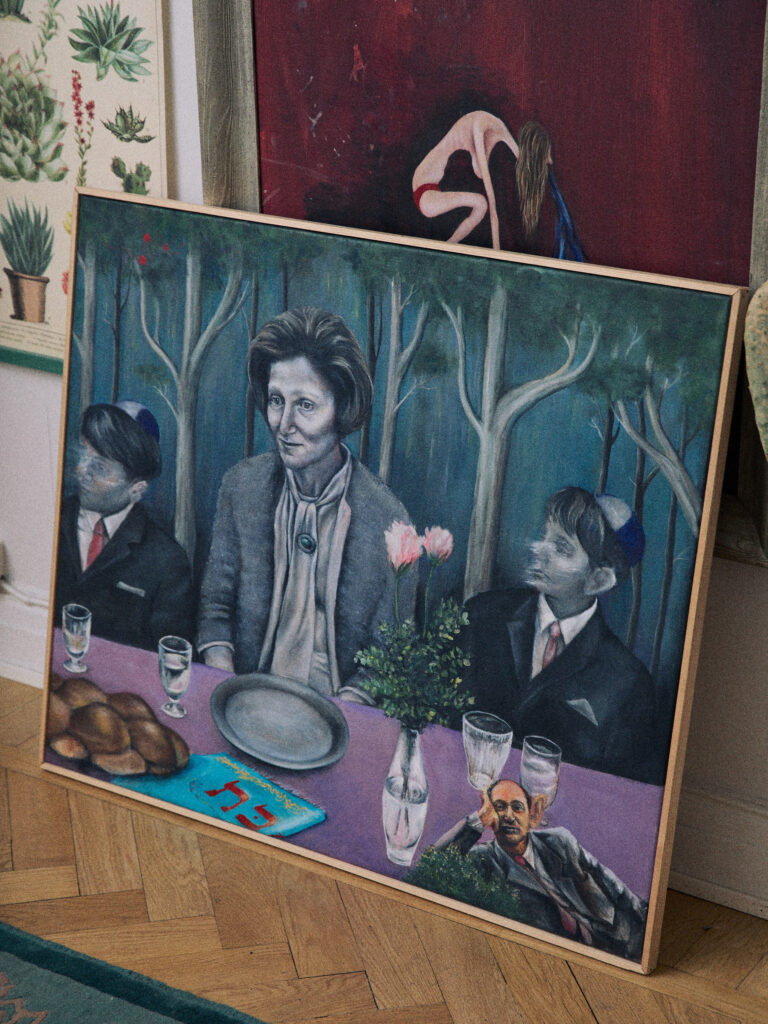

In her paintings, Sanna Fried moves between worlds; the commercial imagery of her former fashion career, the emotional intensity of female surrealism, and the lived realities of women who stand outside narratives.

Speaking with Odalisque Magazine, she reflects on returning to fine art, the women who shaped her visual language, and the ongoing project that challenges the ways society interprets female autonomy and desire.

Elsa Chagot: You began your career in fashion before fully turning to painting. How has that background shaped the way you approach art today?

Sanna Fried: Although painting has always been my deepest passion, and I went to a foundation art school, Nyckelviken, in Stockholm, at 23 my focus shifted towards fashion. Unexperienced, barely speaking English, but with a determination, I moved to New York City to fulfill my dream to work as a fashion editor. Suddenly a formative decade had gone by, working with clients such as Vogue, Vera Wang, Cartier, and Missoni but I felt something was missing me- the art!

The beginning of the pandemic became a turning point for me and I felt the call to return to fine art. I spent the first part of the pandemic on a beach in Costa Rica where I spent my time studying art and practicing, painting oil on canvas but also murals.

In my search for what is my artistic voice I found inspiration in the female surrealist movement and artists like Remedios Varo, Dorothea Tanning and Leonor Fini together with masters of expressional portraiture like Mary Cassatt, John Singer Sargent and Diego Rivera.

The inspiration I found in the history of art began to intertwine with my greatest influences from fashion photography. I’m deeply inspired by Paolo Roversi’s portraits- how a single image can hold an entire story, and by Richard Avedon’s In the American West– where he in portraits reveals the soul of his subjects using no more context than a white backdrop.

Like Warhol, my years in the commercial industry eventually led me back to the path of creating fine art, now deeply influenced by the language of commercial visual storytelling, and fashion photography. This foundation continues to impact my painting, inform my compositions and my curiosity in challenging what an image can be.

EC: You cite artists like Remedios Varo, Dorothea Tanning, and Leonor Fini as influences. What draws you to these female surrealists?

SF: In the later part of the pandemic I moved to Mexico City and ended up being Mexico bound for about 2 years. There, an entirely new visual world opened up to me — shaped by Mexico’s centuries-old cultural heritage and its long traditions of visual and artisanal arts, and reflected so clearly in the city’s many museums and cultural institutions.

One of the first things I noticed was Mexico’s tradition of honoring female craftsmanship. Because of this, female contemporary artists have, in a very organic way, been given the spotlight they deserve. Discovering women artists who are barely mentioned in European and American art books — yet in Mexico are considered part of the country’s most important contemporary heritage — was extremely liberating for me.

The women you mention were the ones who spoke to me the most: female artists working during modernism, going their own way. Using the bold colors of fauvism, blending rich detail with surreal elements, and bringing forward their most personal thoughts and emotions without censorship or fear — through their art.

art Sanna Fried

My own art has always been about not trying to satisfy the audience, but instead addressing the subjects that matter to me — and mental health is one of the most important among them.

These women all had roots in Europe, yet each of them found her artistic identity through Latin America. I relate to that. I’m a woman from Europe, a context where female artists have always been, and still are, underrepresented. Finding my own artistic voice in Mexico, I discovered in these women not only new inspiration, but also a new sense of confidence as an artist.

EC: You’ve drawn interest from both the fashion industry and female surrealists. What happens internally when those two worlds meet; the commercial and the surreal, the stylized and the raw?

SF: For me, those two worlds meet very naturally. Fashion taught me to think in images — how a single frame can communicate mood, narrative, and identity with clarity and intention. Female surrealism, on the other hand, opened the door to everything that doesn’t need to be explained: symbolism, intuition, and the emotional layers beneath the surface.

So internally it’s not a clash, it’s a dialogue. Fashion and commercial brings structure, composition, and a trained eye for detail; surrealism brings freedom and experimentation.

One part of me builds the image carefully- the other part pushes me to let go a bit and let something unexpected in, or sometimes even something uncomfortable. In that overlap my work starts to feel honest to me and I find the balance between control and instinct.

EC: I’ve heard artists describe their works as their children. What’s your personal take on that idea when it’s applied to your own art?

SF: I can relate to that idea. My paintings do feel like my children in many ways.

Creating a painting is a slow process where you give something of yourself in order to bring something new into the world. There’s care, time, frustration, joy- and then a moment when the work no longer belongs to you, but has a life of its own.

EC: You lead community workshops combining art and hospitality. Can you tell us more about that and its effect?

SF: I started to shape my creative workshops during the first half of the pandemic, when I was living between Costa Rica and Tulum- two places with strong spiritual communities. I needed to find a way to support myself, and at the same time I was discovering the spiritual practices for my own wellbeing. I saw a value in combining artistic, creative workshops with meditative elements, and I began offering them to tourists through local hotels and restaurants.

Sometimes I was paid for the sessions, and sometimes I was invited to stay at hotels longer periods in exchange for hosting workshops for their guests- like an artist residency. It was a very particular moment in my life, far away from everything I had previously seen as stability, the workshops gave me a sense of purpose during a confusing time period.

The effect was mutual: guests found a calm, creative space, and I found a way to stay connected to art and community at a time when everything else felt uncertain.

EC: How do you hope viewers feel when they stand before one of your paintings, or do you “let them go” once revealed?

SF: I met Puma, or Johanna, as her real name is, in Mexico city. We met through mutual friends in a nail saloon. The owner of the saloon who knew I was from Sweden told me she had another Swedish client- Johanna, and then she said with a smile “She’s called Puma, she’s a pornstar”. I knew exactly who she was referring to and then and there I knew that Johanna is a woman I have to make art about.

What drew me to her is the same thing that draws me to many of the women I paint: strong, unconventional women who dare to live outside the box.

I followed her for about six months, documenting different parts of her life: domestic life with her cat and her boyfriend of a decade, her work with plant medicine, her work as a fashion designer, and her daily job in the adult film industry. What I discovered was a highly professional, hardworking and very smart woman. She’s an entrepreneur and she’s making money on her own terms. Visually, I’m fascinated by her body, the way she has shaped it by choice is, to me, a kind of living sculpture.

She completely shifted my understanding of what it means to work in adult entertainment- it’s like any other job- but sadly, with a history of really bad working terms. However, the platform OnlyFans has made the work much safer for women like Johanna. By using OF, they stay physically safe, are guaranteed their payments, and get to be their own bosses. Through my project with Johanna I aim to highlight the absurdity of the contemporary social media regulations (like the censor of women’s nipples) and the Only Fans bans, and tell the story of the damage it does not only to women’s rights but also to women’s possibilities to make their own money in a safe way. The IG censorship is by the way also a big issue for artists looking to promote their work containing any nudity. A few years ago even the Naturhistorisches Museum in vienna got censored after posting a photo of the Venus of Willendorf…

I’m drawn to this project because it reveals how society treats women who step outside accepted roles, and I want to challenge that through my work. Johanna’s story exposes the gap between how a woman is seen and who she actually is. Working with Johanna has also shown me how quickly those attitudes spill over onto me as an artist working with her.

After I shared the project with a well-established figure in the Swedish art world, his response was to sexualize me — proposing an “artistic meta project” where he would fantasize about me while watching me study a naked Johanna. It was a clear reminder of how quickly women are reduced the moment we approach subjects connected to sexuality: our professionalism is questioned, and our boundaries become negotiable in other people’s eyes. This strengthened my motivation to continue the project. It confirmed exactly why this story needs to be told – not just for Johanna, but for the broader conversation about how women’s narratives are handled, misread, or dismissed.

The project is still in process, but my intention is clear: to portray Johanna, aka Puma Swede, as the complex, multifaceted person she is, and to challenge the assumptions around female sexuality, autonomy, and agency. It’s not a commercial project in some perspectives, but at the same time, making art about a woman with a million unique followers on instagram- isn’t that commercial if anything?

EC: You’re returning to Mexico for a couple of months, what draws you back? Is there something about Mexico’s culture, atmosphere, or energy that you find uniquely inspiring compared to Stockholm or other places you’ve worked in?

SF: I go back every year- I can’t stay away. These days I can’t stay for as long as I would like, for both practical and financial reasons, but I always allow myself a few months there.

Every place has its own charm, and in the end it’s all about who you are and what you respond to. For me, Mexico has given me a broader perspective and a more vibrant, colorful source of inspiration. Stockholm, on the other hand, may offer me less of that vivid palette, but it gives me something else important: a sense of home, stability, and a social safety net.

I once heard an interview with the artist Britta Marakatt-Labba, where she described spending her summers in the forests of northern Sweden with her reindeers, not producing art, just being present in the rich nature. Then in winter she would withdraw indoors, almost in isolation, and focus entirely on her artistic work.Maybe my months in Mexico are my version of those summers in the woods – a time to absorb, observe, and refill. And Stockholm becomes the place I return to for reflection and the quieter focus needed to actually produce the work.

EC: Finally, what does the next chapter look like for you?

SF: To be fully transparent: I’m an artist with a restless, nomadic nature constantly in search for inner satisfaction that I never seems to find. I don’t know exactly what the next chapter will look like…

I can tell you the few things I do know though. The Swedish Museum of the Holocaust has invited me to exhibit with them this spring, something I feel both excited about and deeply honored by.

Apart from exhibiting with the museum, my work with Puma continues as well as my portraiture painting. I will cover Mexico City’s Art week for Odalisque in February and finish my studies in art history at Umeå university.