Light Beyond Reality - The Ethereal Worlds of SOL Summers

text Jahwanna Berglund

“Parhelion” is not just the title of this latest body of work; it is a gateway into an ethereal and mesmerising exploration of light, wonder, and myth. The series delves into the phenomenon of parhelia—commonly known as sun dogs—and uses this rare interplay of light and atmosphere to evoke a sense of the extraordinary breaking into the mundane.

In this interview, the artist Sol Summers discusses the inspirations and creative processes that shaped the series, drawing on everything from the paintings of Edvard Munch to the otherworldly beauty of desert landscapes. The work reflects a profound connection to nature’s fleeting, awe-inspiring moments, as well as a fascination with the idea of contemporary myth-making—placing the unexplainable and magical within the everyday.

From embracing new materials and techniques to reflecting on the cyclical nature of artistic exploration, “Parhelion” represents a significant evolution in the artist’s oeuvre. Yet, at its heart, it maintains a consistent thread: a desire to distill life, energy, and emotion into each painting. Through this series, viewers are invited to pause, reflect, and perhaps find a mirror to their own sense of awe and discovery.

As “Parhelion” debuts at the Untitled Art Fair during Art Basel in Miami, Sol Summers hopes these works resonate on both a deeply personal and universal level, offering a transformative experience that lingers long after the moment of encounter. In the conversation that follows, we delve into the ideas, techniques, and inspirations behind this captivating new collection.

Jahwanna Berglund: “Parhelion” is an intriguing title. Can you elaborate on its significance and how it relates to the themes explored in this new body of work?

Sol Summers: “Parhelion” speaks to the idea of something strange and ethereal breaking through the everyday. It has this quality of otherworldliness that feels as though it belongs to myth rather than reality. I often think about how these phenomena must have struck people thousands of years ago – they must have dropped what they were doing and stood, staring at the sky with awe, maybe even fear. Back then, things like rainbows or eclipses sparked entire mythologies, stories about gods and cosmic events.

What I’m trying to capture in these series is light that defies explanation – light that forces you into a kind of magical thinking. That sense of wonder, of being momentarily untethered from the ordinary, is what I want these paintings to hold. Whether it’s an atmospheric phenomenon or a lens flare, these glitches of light bring a sense of wonder to the work. In a way, it’s a form of contemporary myth-making, placing something unexpected into a scene to disrupt its familiarity.

NM: You’ve included artists from both Sweden and other countries. How did you choose these specific artists, and how do their works connect to the exhibition’s theme?

Caroline Wieckhorst: It’s been a privilege to work with these amazing artists and their artistry. A key for us has been finding a great mix and balance of art with different expressions and mediums that communicate with and challenge each other and us as viewers. Works that, in different ways, have their own gaze and agency, interacting with our emotions, challenging our perspectives and sometimes what we might take for granted or know to be true. How we interpret the artworks is individual, and this is the point – to shift the focus from how the artists, curators, and critics intend for the art to be interpreted and, instead, how the art itself makes us react and feel.

For instance, an artwork that very literally gazes back at me is Ulla Wiggen’s eye, Iris. With its ice-blue colour, it’s hard not to feel watched and pierced through your inner thoughts. But is this how you would interpret or feel about this work? And Karon Davis’ sculpture Echo & Narcissus: Looking Glass, speaks to me about the fragility of life, with the plaster that is lightly pieced together and at the same time it holds a certain power and grace, that makes me act with a high sense of respect around it. Paloma Varga Weisz’s large bronze sculptures, Wilde Leute, make me want to hang and sit with them, despite their intimidating size. And Charlotte Gyllenhammar’s child sculpture, Beholder, makes me wonder what she is thinking of and how I best approach her. While Marie-Louise Ekman’s huge floor piece, 30 bilder, with her characteristic comic strip motif, makes me break the rules and let loose my inner side, walking all over the piece and acting more like a rebel. Or at least, trying to.

LH: As Caroline mentioned, we aimed to create a thematic show where various aesthetics and perspectives are represented, with the body as a central theme. Some pieces are abstract, others figurative, but to me, they all convey a sense of the body. For example, Kennedy Yanko’s sculptural work using scrap metal and a material she calls paint skin – formed by pouring large amounts of paint onto a flat surface, which is then shaped and manipulated as it begins to dry – to me says something about what it is like to inhabit a body. It’s perfectly balanced yet also twisted and strange, pieced together in an oddly familiar way. Some parts of the work speak to me in more subtle and ambiguous ways, but this only strengthens its impact. Not everyone will interact with it this way, and it’s not an “intended” reaction, but that’s why we wanted the show so rich. I hope that at least one piece in the show will challenge, unsettle, or make each viewer feel self-conscious.

NM: The exhibition suggests that the artworks might be ‘looking back’ at the viewers. How do you think people will feel about this idea of being observed by the artworks?

CW: Aren’t we always being watched or observed? I think and hope that it might open up new ideas about who or what is watching us, and what this might mean to us. Being watched or observed, might not always mean Big Brother is watching. Like I mentioned previously, Wiggen’s work makes me feel watched and pierced through my inner thoughts, but someone else might think of it as a protector, or companion, making them feel less alone.

LH: In the show, some artworks, like Karin Mamma Andersson’s About a Girl and Arvida Byström’s Clown, or Wiggen’s Iris that Caroline mentioned, feature piercing stares that demand a direct engagement from viewers and create a distinct sensation of being watched. The theme might not be intuitive for everyone, but I think it’s the experience many of us have when observing images and objects. W.J.T. Mitchell’s book What Do Pictures Want? was a big inspiration for the show’s theme, particularly his exploration of the power of images beyond traditional semiotic or rhetorical interpretations.

JB: Sun dogs are known for their ethereal and transient nature. How do these qualities manifest in your artwork?

SS: The sun dog is, at its core, a purely visual experience. That’s what drew me to it – its undeniable beauty. The way it transforms the sky, interrupts it, feels like something unrepeatable. But it’s also a symbol, and symbols are slippery things. They mean one thing to you and something else to me. How you arrive at them changes what they mean. What it represents to me might not be what it represents to you, and that’s fine.

For me, a sun dog represents the impossible breaking into the everyday. It’s a reminder that the world is strange and magical if you look at it long enough. That’s what I want my paintings to hold.

JB: What emotions or messages do you aim to convey to the audience through this collection?

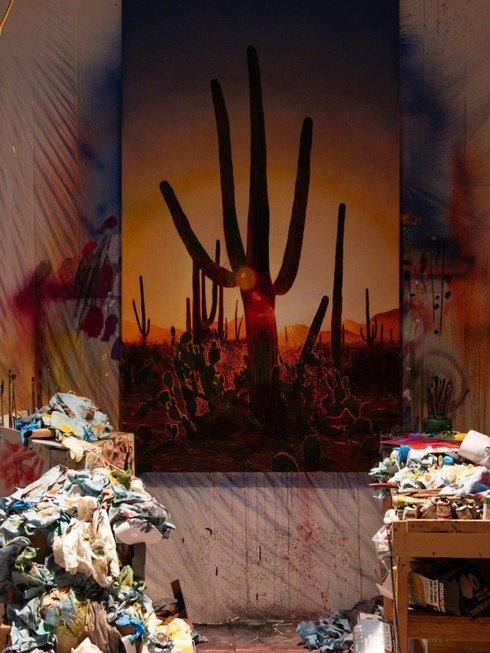

SS: In preparing for this show, I spent a lot of time in the deserts of Nevada and Arizona. What struck me is that the desert isn’t just a place – it’s a mirror. It reflects who you are, shows you aspects of yourself you might not have seen before. I hope these paintings can serve a similar purpose for the viewer, allowing them to find something personal within the work – something that says as much about them as it does about the paintings themselves.

For me, the emotion that resonates most in this work is awe. When I was a kid, I would stand in front of massive landscape paintings in museums – works by artists like Kuindzhi or Friedrich – and feel something so profound I couldn’t name it. If I’ve managed to create something that evokes even a fraction of that feeling for someone else, then I’ve succeeded.