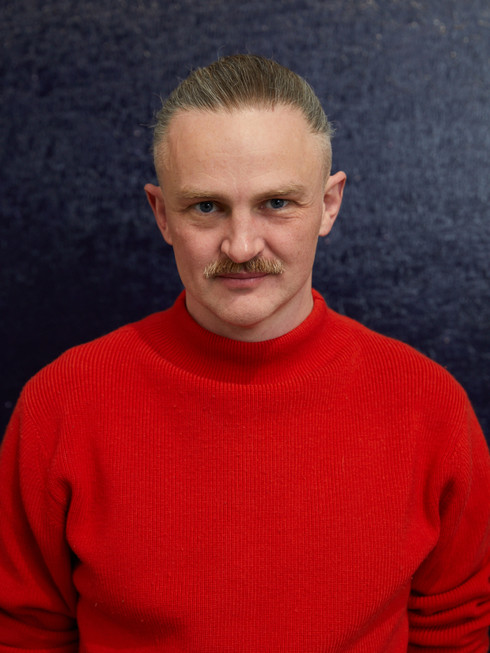

Paul Fägerskiöld: Mapping the Mind through Painting

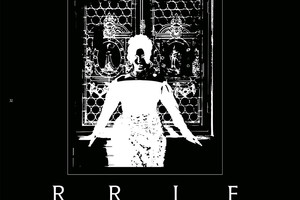

Written by Sandra MyhrbergIn his latest exhibition at Lützengatan, Paul Fägerskiöld unveils a new series of raw, introspective paintings. These works, featuring vertical structures on fields of color, explore the essence of image-making and the act of painting itself. Using symbolic pillars and shelves, the paintings act as blueprints of a cognitive “mind palace,” where abstract forms transform into recognizable images.

Rooted in art history, the series draws from 18th-century Korean Chaekgeori and the Renaissance interplay between Disegno and Colore. Fägerskiöld continues to evolve his visual language, offering a fresh perspective on the relationship between form, color, and meaning.

You work a lot with time and space. Can you elaborate on your view of the present?

I don’t know how abstract one should be :) On one level I think of all segments of time as parts of a 4-Dimentional sculpture. Seen from a different perspective all the things we base our experience of the world on, before-after, cause-effect, history-present-future would all form an entity containing all its stages. In other words the chicken is both egg and hen at the same time, seen from this perspective In a more reality bound view the present is our experience of time passing. The interface on our journey through space-time.

What does your working process look like?

Like most things I work cyclical. And there are many different cycles ongoing at the same time. I constantly collect ideas, do sketches, take photos and reflect on stuff in the studio. Some of those ideas or notes from my notebook hold more than I first thought and after a couple of years they start to connect to other ideas and it becomes necessary to investigate them more. This is done by doing a lot of “bad” paintings and sketches, trying to reach past the initial often to literal idea. Sometimes there is more. Sometimes I find something along the way, a sketch or an idea that breaks what I had initially intended and opens up for something more interesting. In a later face of that cycle I start to make choices regarding what that work asks for in terms of scale, presentation, color etc. And if I ́m working on an upcoming exhibition those choices also relate to the works as a group, what do they add to each other, to the exhibition space, to the viewer passing through the space and while doing so moving through different modes of perception. Once the exhibition is up that cycle continues with reflection, finding new questions and points of curiosity and developing the work from where it was presented in the exhibition.

Can you describe the materials and techniques you use?

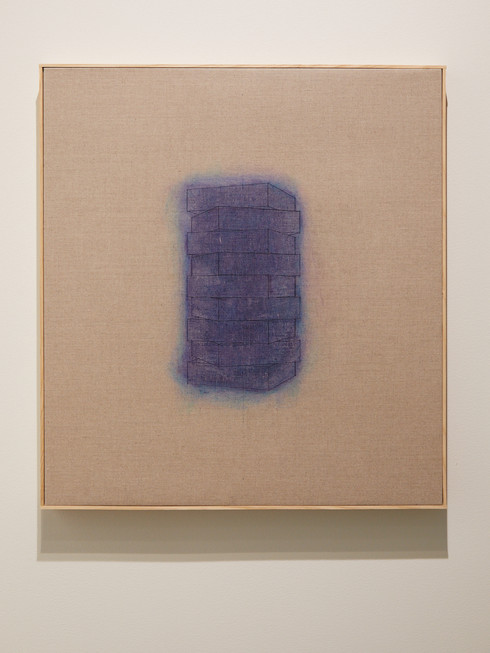

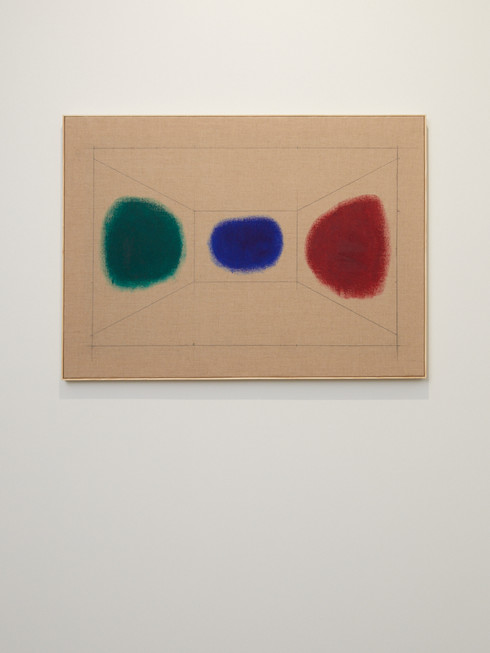

Generally I have been using traditional medias for painting such as oil-paint, gesso, graphite, acrylic on linen. But there is no conceptual block in my work, if the work would ask to be done completely different I would follow. In regards to technique, all the bodies of work I have done has asked for their own way of being made, which often has been very difficult to figure out. Some works has been made with brush, some with spray cans pressed in the wrong way. This show has been done only using cloth and paper to rub layers of paint onto the surface and then remove it, leaving thin layers of residue. And the drawing part of the paintings has been made over layers as well, almost carving into the linen using a graphite-pen. In the end, paint has been caught in the valleys made by the drawing, making the lines both graphite and paint.

What is your relationship with time?

Like most people I’m a mortal human being passing through space time just trying to make sense of it.

I once attended one of your vernissages. There were many layers, and it smelled of paint. Are you often working up to the last minute? How do you decide when a painting is “complete”?

Working towards an exhibition is a quite specific experience and process. It has become a point of total focus for me, I constantly make choices and learn what it is I ́m doing while doing it. The presence and the focus often demands unexpected things from me in terms of finishing the works, they often develop exponentially the last weeks leading up to the show, but even if most of the works are done 2 weeks before the exhibition the last 3-4 paintings that arrive to the exhibition might completely change the direction and the focus of the show. A work is finished when it holds its own ground, when it asks no more of me. When there is nothing I could do to make it find itself. Most of the time the paintings are not as I had thought or intended and part of my work is listening to the work and hearing what it asks for. An unfinished or failed work works the same way.

What drives your artistic practice?

I have for as long as I can remember asked myself questions about transformation and change, trying to make sense of how we create meaning and understanding in the world we live in. Those questions still drive my practice. But on a less cerebral level curiosity, fear, joy and necessity/urgency drive what I do. When something really intrigues me, it tends to be a good direction to go towards, if it at the same time feels a bit scary and fun it tends to be something worth investigating. Or when something feels completely necessary to do even if the arguments are lacking.

Your latest works are described as “cognition maps” or “blueprints of a mind palace.” How do you see the relationship between your inner thoughtsand the visual language in your paintings?

In some regard this show is the result of work I have done over the last two years, thinking about what it would look like painting the creative process itself. But hopefully its more archetypal than just my inner thoughts. I think of the different bodies of work in the show as investigating different modes of cognition. It started with thinking about Matisse’s painting the Red Studio and asking myself how it would work if I painted it. Making a painting of my actual studio felt completely irrelevant, but making a painting of the “mind-space” where I can see all my works at the same time and reflect on the language they all create together made more sense. At the same time I had sketches and notes for memory palaces that had accumulated over the last 6+ years. In cognitive research consciousness is divided into three parts. Perception that deals with the present. Cognition that represent memory and experience, making sense of the new impressions. And Prediction that takes us into the future. We live in a blend between these three nodes. In my work I started to relate the structures or Memory Palaces to the cognition part of this triad. The more abstract small works in the show, using the outline of my previous landscape paintings became a form in which I address perception in itself. Instead of depicting a specific image, scene or landscape, the paintings are interfaces between the world and the perceiving mind, before having made sense of it. The only painting in the show representing Prediction is the painting Tomorrow, it is one of the first paintings I made thinking about this show.

Your work often engages with art history, from Renaissance debates to Korean Chaekgeori. How do these historical references shape your creative process?

I think we as artists (and everyone else) live and work in a shared language, we add our part and play with, correspond to colleagues that were alive long ago in different parts of the world, at the same time as we participate in discussions with artist still not born (hopefully). It is difficult to answer how it shapes my creative process since I cant stand outside of it. It is a tremendous freedom and joy being in dialogue with artists and works I have thought much about. Since I come from a family of artists it has been my experience all along, we take up somebody’s idea, do something with it, and pass it back. Much like Jazz. Sometimes that idea is found within the family, sometimes in a different time on the other side of the world and sometimes somewhere completely unexpected.

Your paintings use monochrome hues as a base.

How does the use of color—or its absence—impact the meaning of your work? I generally strive to have the work be as clear and precise as possible, if it is necessary to add colours and make the work polychrome, I do so. But with specifically the Memory Palaces in the show the structure of them has demanded less action in the paint, otherwise the result has been to chaotic and lacking focus. Even if a painting is perceivably a monochrome I very seldom use one colour to make it. The green Memory Palaces in the show for instance are made with at least four different colours of green, one layer going to very warm yellowish green and one layer towards turquoise. In the end the differences in layers is difficult to notice but the end result is much more vibrant and alive than a monochrome done with the same color.

2024 Paul Fägerskiöld / Nordenhake

Mind Palace

On view 09.11 – 21.12.2024