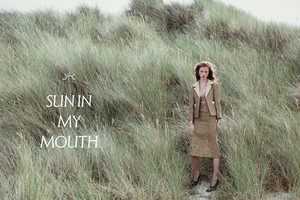

photography Stephane Maffait / Merrild Studios . total look Herskind shoes Apair |

dress Vivienne Westwood knit mfpen glasses Henrik Vibskov |

| total look Herskind shoes Apair |

dress Remain top Maria Scharla |

coat and glasses Henrik Vibskov dress Remain shoes Apair |

dress Vivienne Westwood knit mfpen glasses Henrik Vibskov shoes Apair |

knit Wax London chain dress Vintage shoes Apair |

dress and top Maria Scharla skirt Herskind gloves Arv shoes Apair |

| photography Stephane Maffait / Merrild Studios fashion Fadi Morad hair and makeup Sanne Anndriani / Le Management model Mia Delgado / Independent Mgmt production Karna Maffait post production DOBBELTV |

dress Herskind skirt Maria Scharla shoes Apair |