WOMEN MAKING ART HISTORY AT FRIEZE ART WEEK IN LONDON, OCTOBER 4-7, 2018

Written by Ksenia RundinFor the sixth year in a row, the Frieze art fair has created a showcase of contemporary art in the middle of Regent’s Park. However, this autumn Frieze London has had a female-centric agenda, emphasising female artists in the contemporary context. The visitors could both discover new artists and rediscover those who had fallen off the radar, explore something more in-depth and experiential.

Nevertheless, the main course of the fair has still been aimed at the dealer booths and the wide array of art for sale, the theme of female visibility has acquired a new highlighted ideological perspective. In 1971 the American art historian Linda Nochlin wrote in her legendary essay “Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?” that “the question of women’s equality—in art as in any other realm—devolves not upon the relative benevolence or ill-will of individual men, nor the self-confidence or abjectness of individual women, but rather on the very nature of our institutional structures themselves and the view of reality which they impose on the human beings who are part of them.” Celebrating the centenary of women´s suffrage this year, Britain has also celebrated the female artistic achievements and their concomitants, which have challenged the established stereotypes in the social structures of the art world.

While entering Peres Projects’ exhibition space, the visitors could observe a woman sitting on the floor with the face turned away. Soon one would discover that the face is nothing more than an empty black hole, causing an ambivalent combination of the personal and the alien somewhere inside oneself, followed by a laughter and a fear. There is, according to artist herself, a reflection of a layered identity, where the personal and the abstract seem to be in a constant emotional battle with each other.

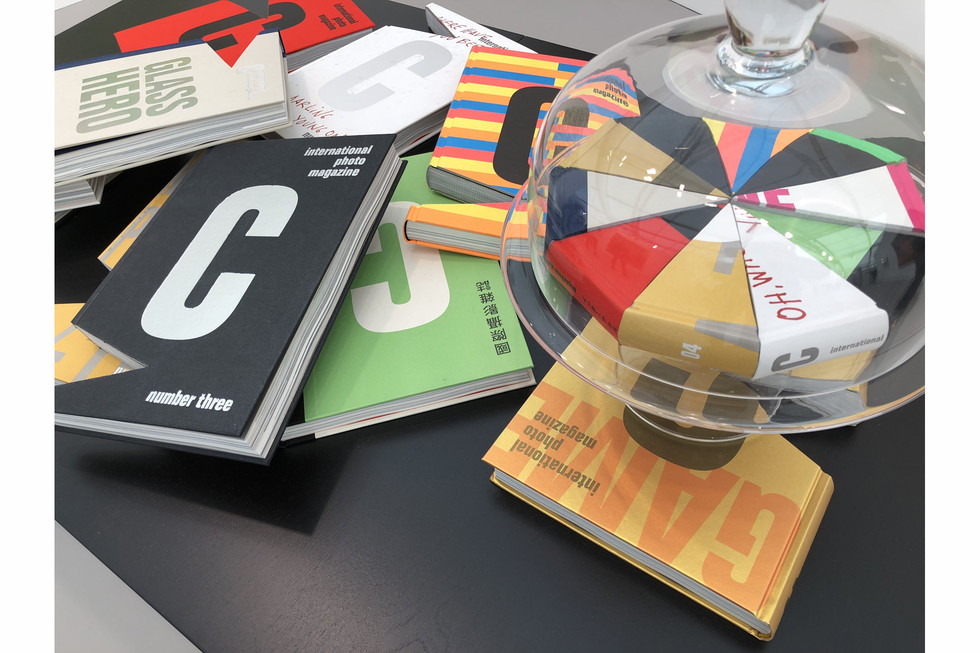

The Cuban artist Glenda León, represented by the Galería Juana de Aizpuru (Madrid, Spain), offered the audience a slice of C International Photo Magazine as her work “Fragmented readings II”, formed in a cake served on a classic pedestal with a glass lock over it.

The London gallery Pilar Corrias, run by Pilar Corrias, who offers 65 percent of the art space to female artists, featured works by such female artists as Sophie von Hellermann, Cui Jie, Helen Johnson, Koo Jeong A, Tala Madani, Sabine Moritz, Christina Quarles, Mary Ramsden and Tschabalala Self.

In parallel with the Frieze London art festivity, Swedish artists have tempted the public by a cogent installation group called Fashion Speaks “Sisterhood”, designed and produced by the Belarussian-born Sweden-based artist L Christeseva, consisting of discarded toiles — prototype garments, collected from the prominent Swedish designers. The installations would make the audience wonder what sisterhood means for each of us coming from different cultures and families in particular, as well as for us –- women –- today in general? Based on a personal story of her own, the artist could illustrate how a fashion garment becomes an emotional symbol that provides a way to learn how to unite and support each other. When being a little girl during the World War II, her mother had to wait for one of her sisters to come home from school to be able to wear the only dress all the sisters shared in order to go to school herself, while the other sisters would wait for her to return.

The exhibition Fashion Speaks Sisterhood was brought to London in order to support the international project Artdom, upheld by the Embassy of Sweden in London and curated by the Goodwill ambassador of Swedish National Committee for UN Women Arghavan Agida, who by means of art seeks to build bridges between Iranian and Swedish female artists.

Revealing an intellectual deepness, framed by the institutional weakness of recognizing the full creative potential and conspicuous importance of the female art, the women at the art fair have sincerely displayed their outstanding artistic talent, grinded by hard work, surrounded by cultural-ideological biases and inadequacies. Frieze London might have bestowed them an opportunity to face up to the reality of their history in order to re-construct their future in the art world.