Joachim Trier

Written by Blenda Setterwa...One thing that can be said about Joachim Trier is that he is bold and unpredictable as a filmmaker, expanding his comfort zone with every new film.

Oslo August 31, Trier’s second picture, he had already generated a faithful fanbase who are now following his career with anticipation. This position can also become a trap, placing you in a box or leading to crowd-pleasing maneuvers where directors tend to create the same movie over and over again with small variations. With his fourth film Thelma, Trier proved he's about to do quite the opposite and took on a completely new genre. Thelma is sensual, claustrophobic, nerve wrecking and beautiful

Over the passed decade, Trier has emerged as one of Norway's biggest directors. Thelma has been announced as the Norweigians’s Oscar contribution this year and is being distributed in 95 countries. Comparisons have been made to everything from the legacy of Ingmar Bergman to the Netflix hit series Stranger Things, Oscar winning thriller The Black Swan and the Swedish cult film Let the right one in.

B: You’ve made a film about a young woman from a deeply religious Christian family, who falls in love with another girl, discovers her sexuality and her supernatural powers that she doesn't really know how to control… How did you, being a grown-up man and proclaimed atheist, become interested in telling this story?

J: That’s a good question. What’s interesting is creating a character, via an actor, by trying to find a human contact with her. For instance, I too know what it feels like to feel the need to be in control when you're not in control at all. And the film is very much about losing control. I too have experienced unhappy love, even though it's a different kind of unhappy love.

I think the film is an attempt to speak to people who are different from yourself. Older or younger. I’m absorbed by the existential theme of being a young person experiencing love for the first time, breaking free from close family ties, trying to become an individual and the shock that can create.

The first idea to make this movie was a manifestation of the psychological in a physical body. Her having an epileptic seizure surrounded by people. Me and Eskil (Vogt) who I write with always work from situations that we find interesting in order for it to come naturally. In this case we saw the story as kind of a feminist witch tale, where you side with the witch.

I myself have a background in subcultures and punk, which makes me treasure the perspective where you see the good in magic.

B: One thing I thought about regarding the magic, connecting love between two women to witchcraft and dark supernatural powers is something that has been done in not so very positive ways throughout human history. Did that worry you at all when you decided to take on this theme? Dit it make it harder?

J: Well, I wanted to approach it the other way around, to turn it into something positive, into a beautiful story. I think everyone who sees it understands that we're rooting for Thelma. Even though it’s complex and you’re supposed to feel ambivalence regarding her moralic persona and such. And, it’s a shout out to everyone who’s ever felt like a freak. On what premises do we accept ourselves? That's the core of being a witch.

B: All your movies are very different from one another, in theme and expression. You don’t stick to one particular style or theme like a lot of filmmakers do. Why do you think that is?

J: I think there's something very cool in exploring variation in themes and genres. Growing up, I loved Stanley Kubrick for instance, that's what he did. Regardless if he made Si-Fi, war, horror or costume drama, it was still always Stanley Kubrick. Because he let some time pass between his films and developed the ideas himself, the movies always had a unique feel to them, whatever genre he did. I was very inspired by that, doing a genre. I work in a quiet stable team with the same photographer, scenographer and editors, and we as a team wanted to try this genre. I used to love these types of horror movies when I was younger. The 70s and 80s were really cool decades in film history so we wrote it whiles listening to 80s synth music. Horror today is more about blood, guts and jump scares. I wanted to make something that was more psychologically creeping and supernatural.

B: You have a team that you feel safe with. How important is it to surround yourself with the right things and the right people to be able to be creative the way you want? How did you find those people?

J: It’s tremendously important! Eskil who I write with is an old friend. We met whilst working at a Double or Nothing TV show, as camera technicians. Between takes there wasn’t much to do and we had a lot of time to sit and talk about Fellini, Brian De Palma and movies we liked. After that I attended European Film College where I met my editor, Olivier (Bugge Coutté). He and I applied to National Film School in England, where I met Jakob Ihre, a fantastic film photographer from Sweden. And we have worked together ever since. It’s like an adventure and you pick good people up along the way.

B: …and hold on to them.

J: Yes. Not exclusively of course, they do heaps of other films. I like security and having a team, I’m not a novelist who wants to sit by myself and write. And I hope that we can create security together that can help the actors for instance. All actors are nervous, it’s scary to be on a movie set.

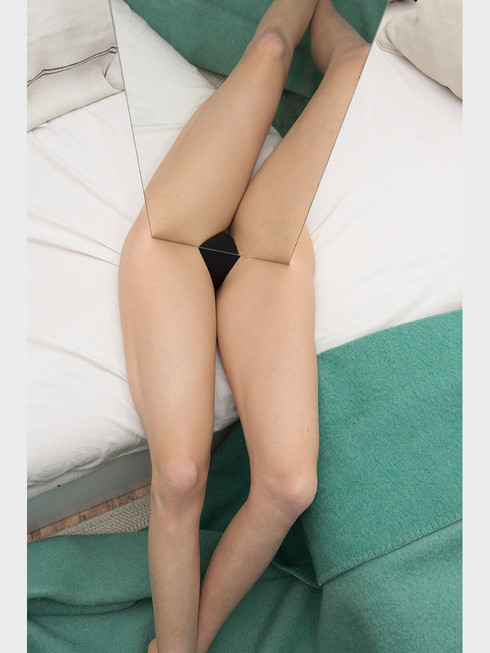

B: This movie seems very aesthetically thought through. It’s intimate and each frame kind of looks like a beautiful photograph. How did you think in regards to the cinematography in this film?

J: It´s perhaps the most important thing of all. It´s very intuitive and personal. Out of all of the movies I have made, I think Thelma is the most dynamic one. It’s very intimate, sometimes almost claustrophobic. At other times it’s almost paranoid, observing Thelma from a far distance. We wanted to play with that dynamic to create tension. Also, these days when so much is produced only for a TV format and filmmakers are asking themselves “Why do big screen?”, I hope a film like Thelma can answer that.

B: What reactions to your films makes you happy?

J: It’s all in the personal meeting. Just a few hours ago after a screening at the Stockholm Film Festival, a women from the audience walked up to me, took my hand and told me how deeply touched she was by the movie. She didn’t say much, however I saw in her eyes that she meant it. So as soon as it means something to someone else, that makes me happy. I love sitting in an audience feeling like I communicate with others and that we’re experiencing something together that goes beyond everyday encounters. That's something art can do. It sounds simple, but it's really complicated. And if I can do that for a person, it means the world. When someone walks up to me to say that Oslo, August 31 has meant something to them in their life, that makes me feel like all the work we’re doing means something too.

Another thing that makes me happy is to see a young actor have an amazing day on set. Like when Eili Harboe who plays Thelma, had one of her best days, it was so insanely good and it was all her own doing. All I can do is support and give feedback. Witnessing that makes it all meaningful. I don’t know what it’s like for you as a journalist, but somehow you always need to look for meaning in what you do. Things aren’t meaningful in themselves.

B: I think there are meaningful moments. And a lot of the opposite.

J: Yes. It’s those moments we’re hunting for.

B: You’re one of the Norweighs biggest directors by now. Thelma has been announced as Norway’s Oscar’s contribution this year, among other things. What is your reaction to this success? Does it affect your creativity?

J: Im continually doubtful. Every time I make a movie I’ll feel like I’ve failed completely at some point in the process. But, then along comes a day where I feel like everything is going to be fine. Ups and downs, that doesn’t change after four films. What's great about having made four films is that I know the process now and feel comfortable in the different stages of it. And of course, it has made it clear to me that success creates a certain amount of pressure.

In a sense I’ve used my last two films to break the pressure that expectations create and get through it. I’ve had some growing pains. This is very personal I suppose but, ideas revolving around ambition and success have been crucial themes in all of my movies. My first movie Reprise is about two friends and their ambitions before knowing that one of them would reach success and the other wouldn't. Friendship and ambition basically.

The second movie, Oslo, august 31 is about a guy who feels like a failure, who hasn’t managed to accomplish anything. Everyone saw him as smart and promising but then he failed at proving anything. Ambition has become a burden for him.

In Louder than bombs, the mother is a successful photographer who doesn’t have a lot of time for her family and the father has given up his ambition to be an actor. Instead he’s a stay at home dad who stands in the middle of conflicts with his sons. There’s something beautiful in that. So, I guess success and ambition is a central theme for me.

Another aspect of success for me that Im dependent on a certain amount of success to be able to make more movies.

What I do is dependent on someone saying “Sure, we’ll give you money one more time”. What I fear the most in that is losing naivety which I think is the core of art and life itself. Investigating something only to find out it’s completely different than you thought it was. If you start creating things looking for ratification from others, you'll realise quickly that it isn’t enough. It’s important that the films have meaning. That’s hard sometimes, I’ve had periods where I don’t know what I want to say.

B: I read a little bit about you and you seem to have a lot of ambition or enthusiasm perhaps, from the beginning. Where do you think that came from?

J: I don’t know. I easily get obsessed with things. Perhaps that's my talent, I’m good at maintaining enthusiasm. I manage to do those jobs where you need to get up at five am to stand outside in freezing snow. That's a privilege. I can’t think of anything else than my movie when I’m on set. Then, I'm completely free.

B: If you play with the thought that you hadn’t had this strong enthusiasm and didn’t work with film, what do you think you would have done then?

J: I don’t know anything else. This is all there is for me. Film is such an interesting way of telling a story, I can’t imagine anything else. Of course, there are moments when I think of an imaginary “after”. For how long will this last? For how long will I have the energy to go on?

But I wonder if film isn’t vitalising. It’s vitalising to be able to work with your whole self. I was in Los Angeles recently at an award ceremony where the amazing french director Agnes Varda was awarded. I think she’s 89 and she still has humour and energy. It’s such a privilege being a director, working in so many different environments, with so many different kinds of people. Like when we were location scouting for Thelma, going out to the suburbs looking at small industrial apartments in east Oslo. We met so many different people, families from Somalia, Old couples, young students… And the next day we’re at the opera meeting ballet dancers during practice, seeing all their discipline. It’s a way of seeing the world.

B: Ultimately your job is like having many different jobs at once.

J: Yeah, that's how I feel.

B: I’ve heard that you only watch your movies once and then never again.

J: How do you know that? Well, that's almost true. I mean, I see them a hundred times when I make them, edit and mix them, over and over again. I do have a tradition to saying goodbye to my films at the Oslo premiere. I watch it there together with my team, family, friends and actors. After that, I try to forget about the movie, remove it from my hard drive so to speak.

B: Is that why you do it?

J: I think so. Otherwise, I just see things I could have done differently. There’s so much you can do. I did se Reprise once more at it’s 10 year anniversary. I had to, the actors were there and everything. And it felt ok, I was kind of proud but, it felt like another me had made it. In another time.

B: What are your hopes for Thelma? Like, in regards to who will see it and who it will affect.

J: I think I’ve made it for anybody who wants to try to understand it. I’m very curious as to how it will be received in different cultures. It’s distributed in 95 countries! There amongst Russia, were the queer culture is very repressed, that feels really cool, having made a gay-romance that's being distributed in Russia. What if someone who goes to see a horror movie also feels like they get a pat on the back? That makes me proud because the movie is very clearly on the side of Love, that's important to me.

B: What made religion an interesting subject to you?

J: It started out as a kind of backdrop for the story. Most Christians in Scandinavia are not at all like Thelma's parents are, her family come from very charismatic and extreme environments. So we did research in places like that. And while doing the research I encountered a lot of people who were very critical towards homosexuality, which is completely unacceptable. It’s extremely tearing on one’s psyche, not being allowed to love who you love. And especially for these young people. I have nothing against the right to personal beliefs, it’s important that people feel they have the right to believe what they want. I don’t have the answers and I find the world very mysterious but, using religion for control, that, I am very opposed to.

B: Was it hard to create a mystery? Being used to creating more realistic movies?

J: It’s a dream come true! To bring fantasy in. What’s hard is showing things the way they really are. I like exploring that and at the same time explore what imagination can do. That's what I hope will seduce the audience. Being invited on a journey into something unexpected and abnormal, seen from our reality. That's what art is for, taking on dreams and fantasies. The film is about what would happen if our deepest fantasies suddenly became real. Would that be really be desirable?

B: It takes place very much in the twilight zone, between reality and imagination. Destabilisation of reality.

J: Yes, we wanted the subconscious to surface. Thats where the deep connections between things lay, that we can’t talk about but show in movies. Death, eroticism, love. Big and important themes that art gives us a language for. When you sit inside a dark movie theatre with other people but alone with your thoughts and relate to those themes. I think that's a healthy way of processing them.

B: If you were to give advice to someone just starting in the industry, wanting to make movies or write, what would that be?

J: I don’t know if I'm any good at giving advice, just to have that said. But since you're asking, watch a lot of movies. Different kinds of movies, to see what a huge language film is. Watch rare movies from foreign countries, japanese, russian movies, to feel what the camera does differently. And, try to find out what your themes are. What do you want to show, what do you want other people to see? How do you make your gaze interesting enough for other people to want to see it? Break rules. Don’t try to satisfy others or create what's expected.

B: Be an active observer?

J: That's very well put, an active observer. See film, see the world and find the language that ties them together. And of course, you can’t just write a script and suddenly become a director, you need to be around cameras, make numerous tests, fail multiple times and try again. I made loads of shorts, like twelve I think.

B: You’ve only released three?

J: Yeah, most of the others are buried or not finished.

B: So, a hidden advice in this advice is to learn how to handle failure?

J: Yes. I like to think of something Philip Roth said. He has been writing novels since the 60’s and still does. He says that every novel he writes feels like a tiny bird that hatches in the palm of his hand, craving nourishment and care. And he always feels like it’s probably never going to fly or even survive, but if he stays brave and keeps caring for it, he’ll soon realise he's created yet another piece.

B: Just this week I read that Norwegian actresses have come together and signed a petition calling out sexual harrasments and inequalities in the industry, just like here in Sweden and many other countries all over the world. This is about your industry and your colleagues. What do you think needs to be done to change this climate? How do you move forward?

J: I think it’s very positive that it comes out in the open and it’s very important to take it seriously. It pisses me off tremendously, all these women who haven’t been listened to, all these stories, I really wasn’t aware of the extent of this problem. There’s so much to say about this and I can’t cover it all now. Basically the way I see it, a lot of these incidents should be handled legally and should be reported. Then, there are grey-zones, things that are completely wrong but not illegal. We need to discuss and debate those grey-zones. Great acting grows in a climate of trust and cooperation which makes this so important for everyone in our industry, both men and women; directors, actors, crew etc. Creating a safe and trusting framework for the things we do. For people to dare to open up and make great art, we can’t have a culture of fear and repression, it has to end. And I think what’s starting now could be the beginning of something great.