Steve O Smith Presents Metropolis AW26

Inside Camilla Pihl’s Universe of Modern Femininity

Inside Camilla Pihl’s Universe: The Stockholm Launch

Michael Kors FW26 – Runway Show – Backstage

Paris for Haute Couture – Zuhair Murad SS26 – backstage

Paris for Haute Couture – Phan Huy SS26 – Backstage

Paris for Haute Couture – Peet Dullaert SS26 – backstage

Femme Fatale: Kristoffer Kongshaug and Empowerment Through Design in Forza Collective AW26

An interview with Wood Wood’s Brian SS Jensen on their AW26 collection

‘Cadavre Exquis’: Bonnetje AW26

INBETWEEN

Saie at OperaSPORT – Backstage

A Journey in Time: Stephane Waser on 50 Years of Maurice Lacroix

STEM AW26 – Backstage

MKDT STUDIO AW 26 – BACKSTAGE

Rave Rvw FW26 Runway Show

Henrik Vibskov | AW26 | CPHFW

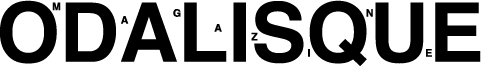

Cole & Son and Vivienne Westwood Introduce New Wallcovering Collaboration

Baum Und Pferdgarten – AW26Airborne

Levi’s CPHFW Street style

Schiaparelli – Haute Couture Spring/Summer 2026 collectie

INSTITUTION Wins the Zalando Visionary Award at Copenhagen Fashion Week

Holzweiler FW26 Runway Show

CHANEL SS26 Haute Couture Runway

OpéraSPORT AW26 CPHFW

Stockholm Surfboard Club’s FW26

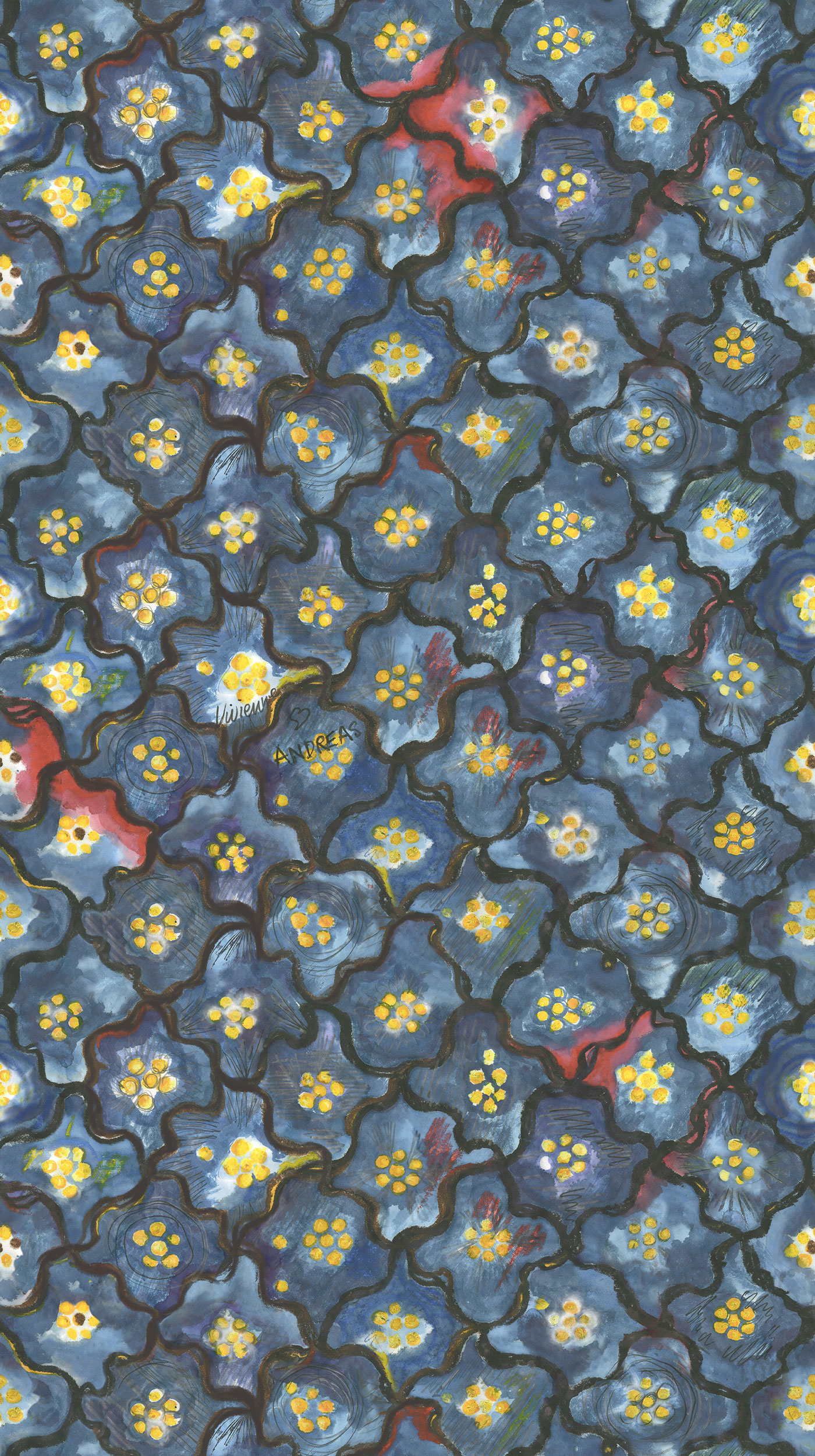

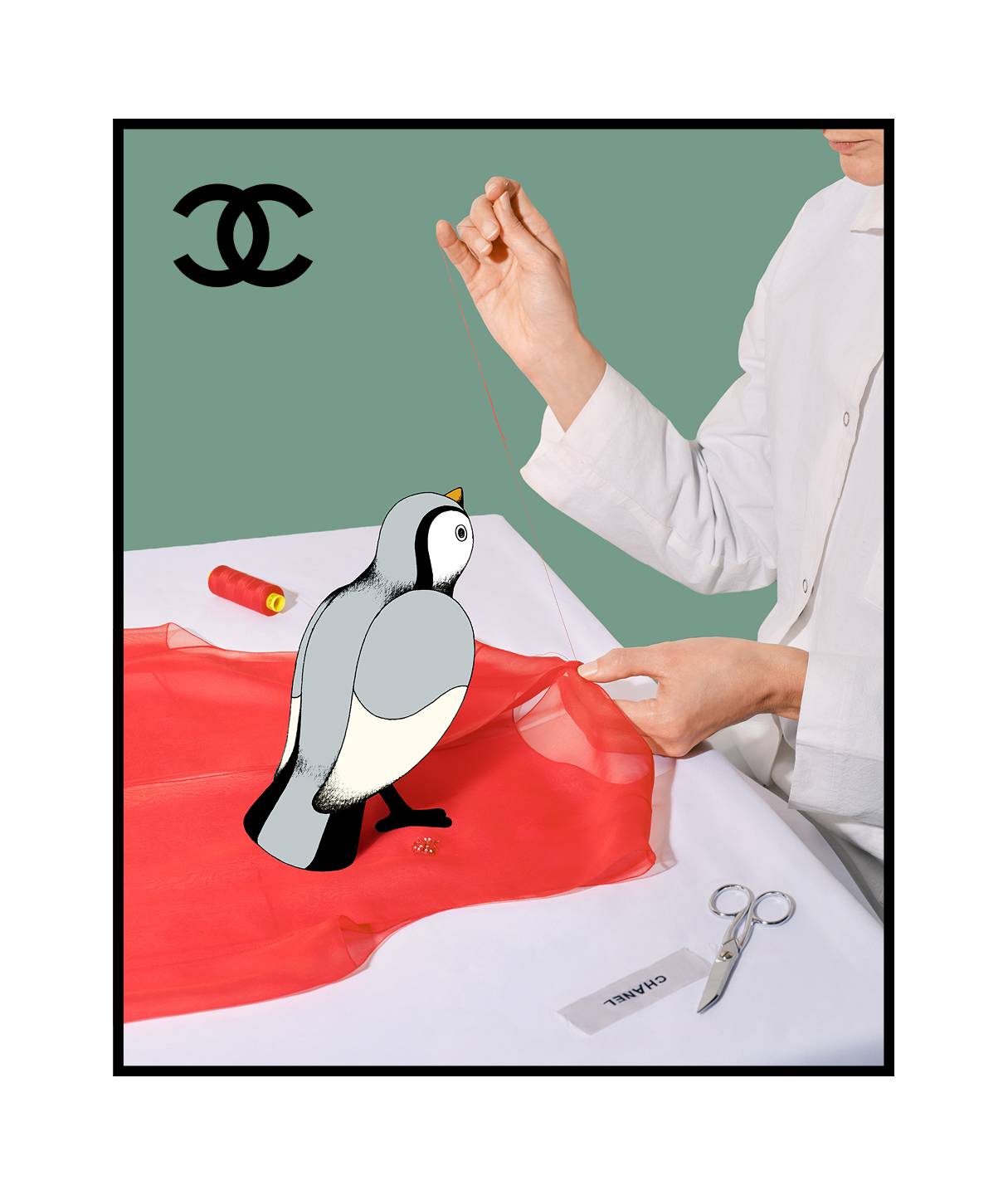

Chanel Haute Couture Spring Summer 2026

CELINE

QASIMI AW26

The CHANEL Spring Summer 2026 Haute Couture show

ISSEY MIYAKE

Soft Armour

Three Times a Charm: Sézane and Sea New York Return

Gucci: La Famiglia: Inside the First Chapter of a New Era

Odalisque Magazine Interviews Madeleine von Schedvin

Frostbite

Night of the Swallow – An Interview With Maria Nilsdotter

Go See

Chanel Beauty Backstage – Métiers D’art 2026

Benjamine Cadette – An Interview With the Designer

Watching You Without Me

Max Palm x Peak Performance: Where Freeride Meets Design

Bringing the Catwalk to the Slopes, an Interview with Sportalm Creative Director Ulli Ehrlich

Sportalm Ski Fashion Show – Backstage

SOMEWHERE IN BETWEEN

ARAKII Opens at Nordiska Kompaniet This December

Métiers D’Art 2026 Show in New York

CLOUDBUSTING – ODALISQUE X BLUNDSTONE

A look inside By Malene Birger’s Holiday Event in Stockholm

SÉZANE – A Love Letter from Paris

All The Love – An Interview With Stefan Pagréus

FOLD-OUT: Tracing Nordic Fashion Magazines

A Dialogue in Couture: Inside the Dual Tribute to Azzedine Alaïa and Christian Dior

Stefano Genco on Nuance Audio and the Future of Smart Hearing Technology

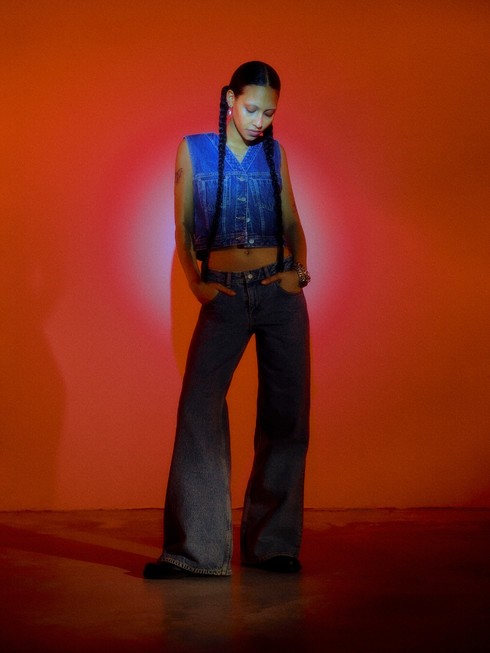

IN SEARCH OF PETER PAN – ODALISQUE X ZALANDO

Johan Persson on NEUW Denim’s Creative Evolution: “Denim Is a Living Material”

Fifteen Years of Maska: Crafting Modern Classics in Natural Fibres

20 Years of Cultural Encounters: SpoilConcept Celebrates Its Anniversary with Eyes on the Future

NE T’ENFUIS PAS

ROOM FOR THE LIFE – An interview with Lan Krebs

ODALISQUE X ZALANDO

ODALISQUE X ZALANDO BACKSTAGE

The Power of Adornment: A Conversation with Mumbaistockholm’s Cecilia Kores

Odalisque Magazine Interviews Leandra Medine Cohen & Linn Frisinger: Integrated Parts — Swedish Stockings

Nicklas Skovgaard — Threads of Memory and Modernity

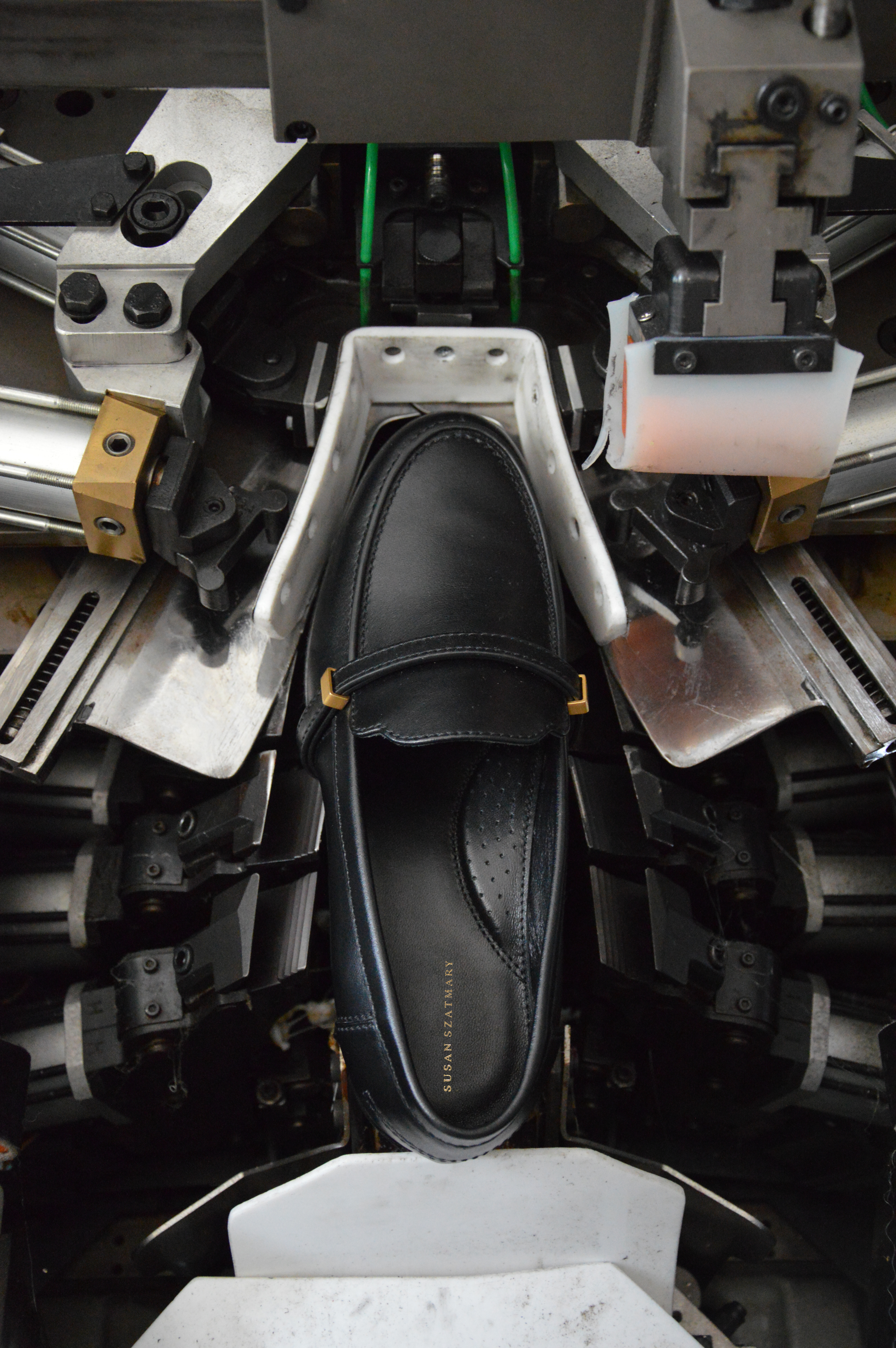

ODALISQUE MAGAZINE INTERVIEWS Susan Szatmáry

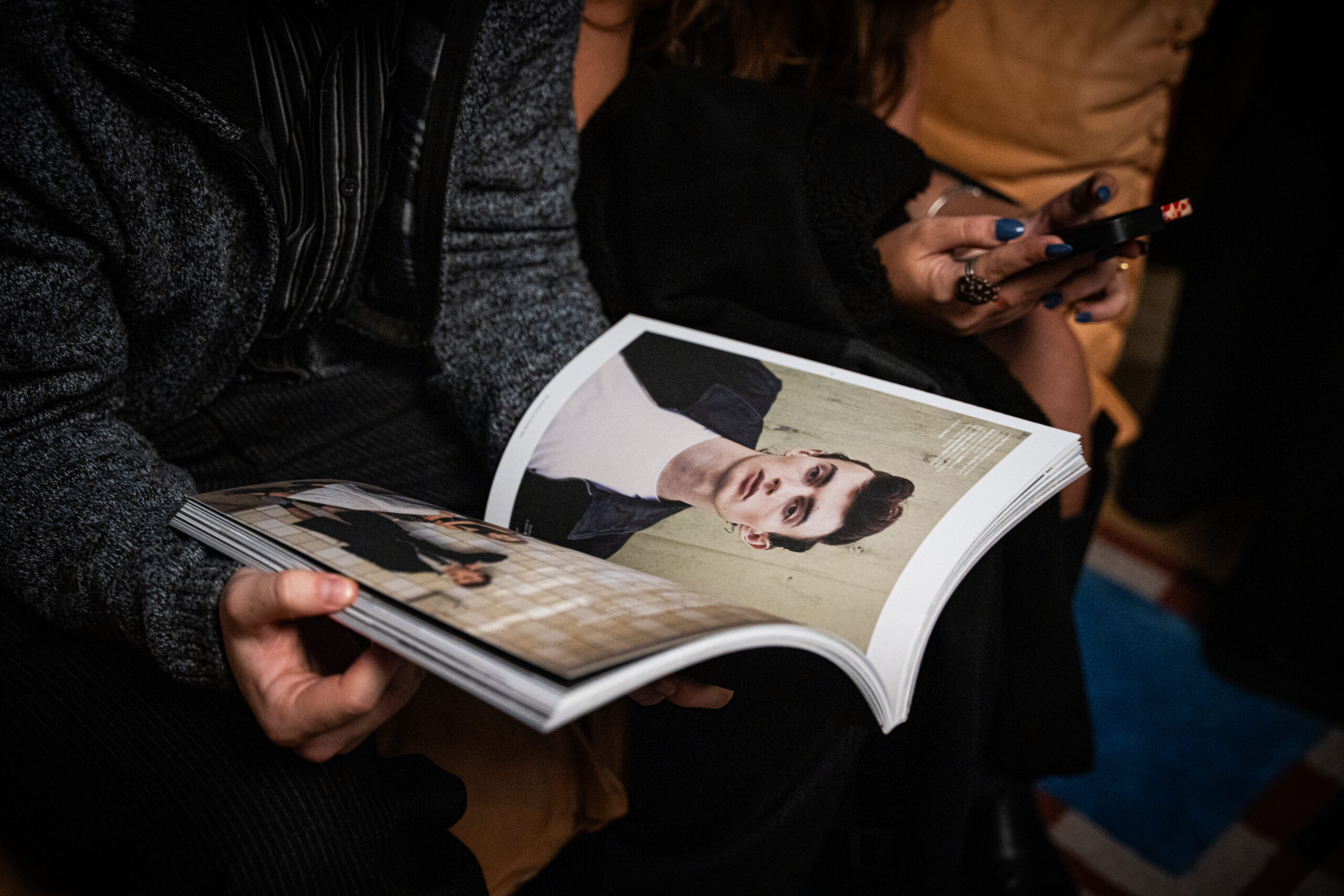

Stockholm Release Party – Odalisque Issue 16

Sprayground SS26

Paul Costelloe SS25

YAKU SS26

ODALISQUE ISSUE 16 RELEASE PARTY LONDON

Kyle Ho SS26

The Art of Comfort: Dr. Martens Expands the Zebzag Sole

BALENCIAGA SS26

SÉZANE: A Fall Chapter

Urban Mirage

Hermès SS26

TRANOÏ X CANEX SS26

BALENCIAGA SS26

CELINE SS26

Magda Butrym SS26

Fashion Scout’s ONES TO WATCH 2 SS26

McQueen SS26

Louis Vuitton SS26

Susan Fang SS26

John Richmond SS26

Noon by Noor SS26

Ray Chu SS26

Jenn Lee SS26

Simone Rocha SS25

Michael Rider Marks His Arrival at Celine with Printemps 2026

sania d’mina Debuts in Nordiska Kompaniet’s Iconic Ljusgården

An Interview with Celeste Lee Arendse: The Interworkings of Her Craft

Evolving Times – Dr. Denim Autumn/Winter 2025

FLOSO: Designing a Future Rooted in the Past

In the Weave of Creation: Four Designers on Fashion, Nature and Norrviken

HEIGS: The Art of Understated Luxury

Lovechild 1979 SS26 Refined Iteration

Between the Thread: A Conversation with Saveja Awzel