Shaping Light and Space: Morgan Persson’s Journey from Color to Cosmic Inspiration

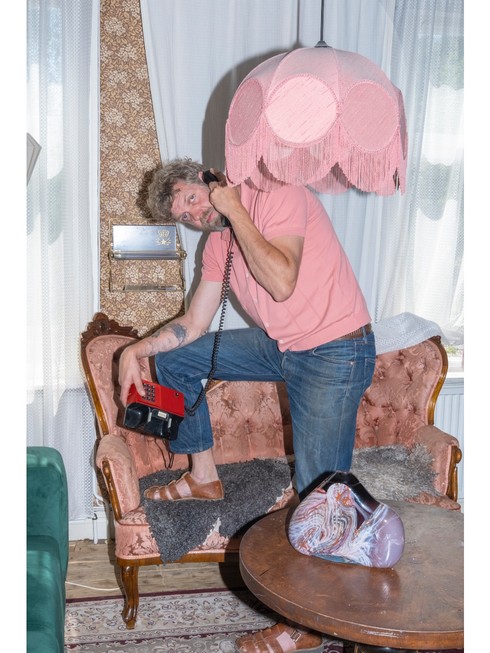

Written by Ulrika LindqvistRenowned glass artist Morgan Persson has spent years pushing the boundaries of his craft. In this interview, he shares the creative process behind his latest collection, The Milky Way, and the inspiration drawn from the vastness of space. He also reflects on memorable projects, the challenges of working with glass, and his vision for the future of his art.

Ulrika Lindqvist: Can you share a bit about your beginnings—how did you first start working with glass?

Morgan Persson: I first discovered glass in my early twenties, and it was a life-changing moment. At the time, I was working as a car painter and playing volleyball at an elite level. One winter evening, I had what I can only describe as a sudden epiphany: I had to dedicate my life to glass. It was a completely unexpected turn, but I followed the impulse, left my job, and enrolled at Glasskolan in Orrefors. That was the beginning of an obsession with mastering every aspect of glassmaking.

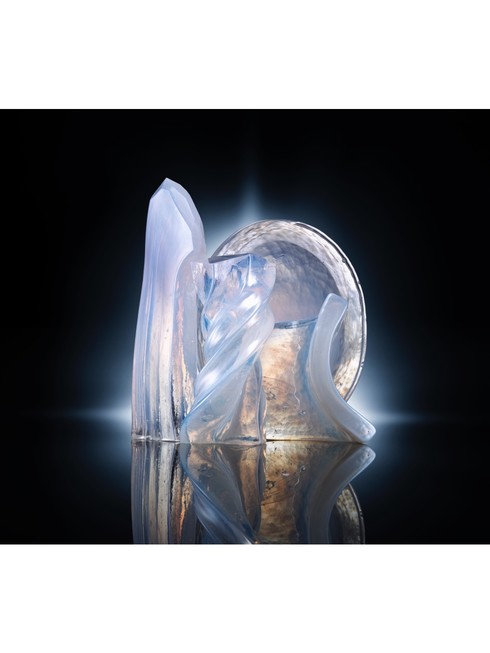

UL: For your latest collection, The Milky Way, you’ve created monochrome sculptures, which marks a shift from your historical focus on color. Could you tell us about this transition and the inspiration behind the collection?

MP: The Milky Way is a departure for me. I’m known for my bold use of color, but this time, I felt drawn to creating something entirely in white. I could picture the pieces before they existed, these “space stones” with a celestial quality. The inspiration came from thinking about stargazing, galaxies, and the vastness of space. It was a challenge to step out of my comfort zone and embrace minimalism, but it

was also exciting to explore how the optical effects of white opal glass could evoke depth and movement.

UL: You collaborated with master glassblower Peter Kuchinke on this collection. How does such a partnership work, and what are the dynamics of your creative collaboration?

MP: Working with Peter Kuchinke was an inspiring experience. He’s a master craftsman with an incredible knowledge of glassblowing techniques. Collaborations like this are all about trust and communication. I brought my ideas and vision, and he brought his expertise and technical skill.

Together, we experimentedand solved challenges,like achieving the desired effects in the opal glass. These partnerships are a mix of structured planning and spontaneous problem-solving, which keeps the process dynamic and rewarding.

UL: What is your personal relationship with space? Are you fascinated by it, do you fear it, and would you ever consider space travel?

MP: I’m deeply fascinated by space. It represents both mystery and endless possibilities, and it inspires me to think about perspective, how small we are in the grand scheme of things. While I find it inspiring, I don’t think I’d personally venture into space. I prefer exploring the unknown from a grounded, creative perspective.

UL: Can you describe your creative process—do you plan and sketch in advance, or do you prefer to improvise? Additionally, what unique challenges or limitations does working with glass present?

MP: My process is a mix of planning and improvisation. I start with an idea or a vision, which I might sketch or just hold in my mind. Once I begin working with the glass, I let the material guide me. Glass is unpredictable, it changes with heat, reacts to different techniques, and demands precision. One challenge is timing; you have to make quick decisions before the glass cools, but that’s also what makes it so exhilarating. I enjoy the balance between controlling the material and allowing it to take its own form.

UL: Are there any particular projects or moments in your career that stand out as especially memorable?

MP: There are several, but one that stands out is the moment I first experimented with recycled glass in collaboration with Leif Hauge. Creating glass objects from seized smuggled alcohol bottles for Tullverket was both challenging and rewarding, it pushed me to think differently about sustainability and design. Another memorable moment was when my family and I moved to Småland to start my own hot shop. That transition marked a new chapter in my career and creative journey.

UL: What does a typical workday in your life look like?

MP: My day usually starts early in the morning with preparation in the glass studio. Depending on the project, I might spend hours blowing, fine-tuning details or working in the cold shop on grinding and polishing. Running a family business means I also wear many hats, managing the showroom, or hosting visitors. It’s busy, but I love the variety and the chance to immerse myself in every part of the

process.

UL: Looking ahead, what’s next for you? And if you could embark on your ultimate dream project, what would it be?

MP: I’m always looking for new ways to push the boundaries of what glass can do. After The Milky Way, I’d like to explore working with larger formats and experimenting more with sandcasting techniques. I’m particularly interested in creating monumental public artworks that could combine glass with other materials. Collaborating with a team on a large-scale project, it offers an opportunity to blend expertise and creativity, which often leads to surprising and powerful results. For now, I’ll keep experimenting and trusting my instincts, as they’ve always been my best guide.