THE BIG SKY - An Interview With Adèle Aproh

text Natalia Muntean

images courtesy of the artist

At five years old, Adèle Aproh copied a parrot from a classmate’s sketchbook and never stopped drawing. Years later, after a detour into business studies and corporate work, she returned to what had always been her private language. “I didn’t really have a choice,” she says. “I needed to draw.” Today, her intricate compositions, inspired by fashion, performance, and ritual, are both therapeutic and theatrical, opening space for viewers to find their own narratives. “They’re stories within stories,” she explains.

Natalia Muntean: Do you remember the first drawing you did?

Adèle Aproh: Actually, yes, I do. It was a bird, a parrot. I was in elementary school, maybe five or six years old. There was this girl in my class, Marie, and she was drawing parrots in a certain way. You know how kids just go from one line to another, and you don’t know where it’s going, and then at the end, you have a bird? Like she was following a scheme. I was fascinated. I thought, “Oh my God, it’s magic.” That is literally how drawing started for me, thanks to this girl. I thought, “Wow, you have a magic trick to draw parrots.” So I started like that, drawing tons and tons of birds for I don’t know how long. Since then, I have always kept drawing. All my school books were full of drawings in the margins. It was a big mess until the end of high school.

NM: So it was always meant to be.

Adèle Aproh: Yeah, kind of. I always dreamed of it. That’s why it was tricky for me to choose at the end of high school. But yeah, no regrets on the business path.

NM: It’s good that you tried it. Now you did that, and you know what it’s like.

Adèle Aproh: Yeah, exactly. This is also where I think I’m lucky. I’ve been there. I know what the corporate job is, and I also know I really don’t want to go back there. So I think that’s another motivation to keep doing what I’m doing. My boyfriend is also an artist, and he’s always been a painter. Sometimes you seek stability, and when you don’t know something, you might wish you were in an office because you don’t know if it’s meant for you. I had the chance to know that if I had a choice, I’d rather be an artist now. Even though it’s unstable and it can be scary, and even though you don’t know what tomorrow is made of, this is really where I want to be.

NM: Your work pulls from a very rich palette of cultural influences, from fashion to comic books to memory. Can you tell me a little bit more about these sources of inspiration?

Adèle Aproh: I have many different inspirations. Fashion has always played a very instinctive role in my work. I think of it as a form of coded communication, a kind of language. Also, the characters in my drawings are all kinds of based on me. I use myself as a model for the poses. I’m not explicitly drawing myself, but as I’m free and available, I take videos of myself. So they all pass through me. They’re not me, but they pass through me. That’s also why they all look like each other. I always used clothing as a way to distinguish them, to create thought, so they all have their own identity.

NM: To separate them?

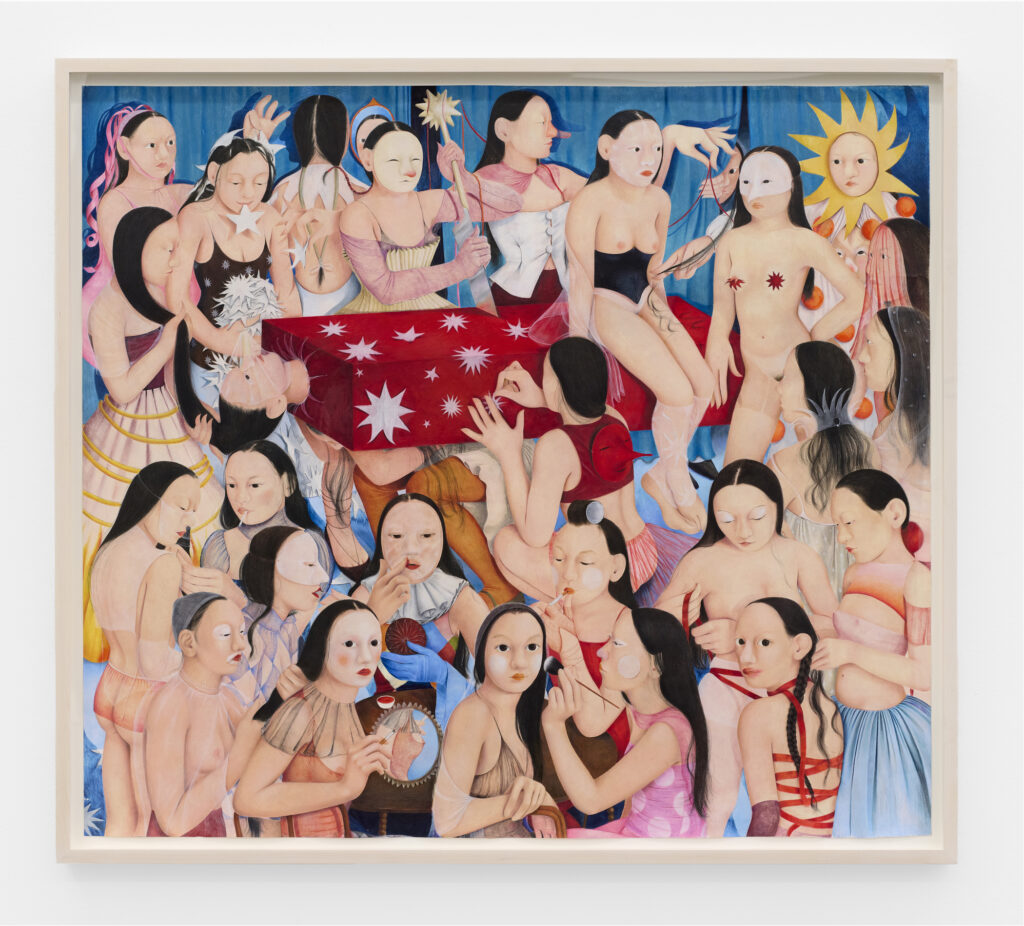

Adèle Aproh: Yes, exactly. I’ve also always been fascinated by historical costume, ballads, uniforms, circus attire, and anything that carries a sense of ritual and theatricality. I often see figure dressing as a kind of choreography. It’s about how identity is compared to movement and material. Also, when I work on a series, I often go to a library in Paris.

NM: I read that you do that every week.

Adèle Aproh: It depends on the regularity of work, but I often go. It’s the library of the Musée des Arts Décoratifs. So it’s focused on visual art and fashion. When I go there, I always take a ton of books on design or works on costumes and layering. All my mood boards are full of archives from this library, so that obviously directly inspires my work. Also, I grew up with a mom who loves fashion. She was, and even now is, literally addicted to shopping. So clothing has always been important. I grew up in a family where fashion was important, so I think I developed a kind of sensibility toward it.

NM: Can you tell me about your sources of inspiration and how you bring them together? I know you’ve mentioned Diego Rivera, but also Alice in Wonderland. How do these influences mix in your work?

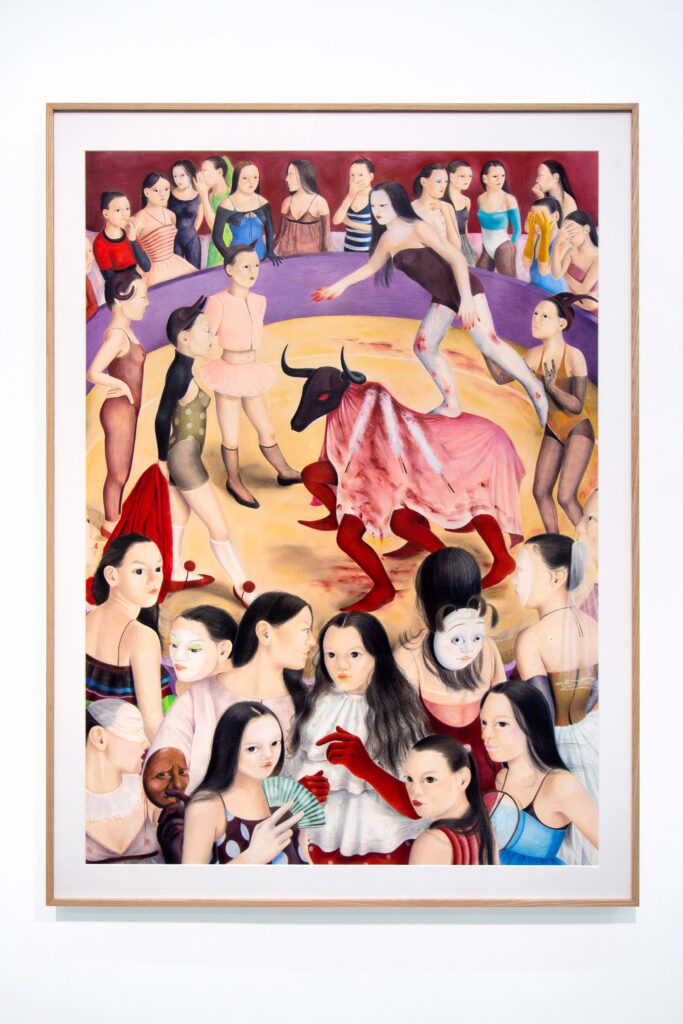

Adèle Aproh: I’m really inspired by what surrounds me – what I see, watch, or read every day. My influences move with my daily life. I can be inspired by a movie I watched the night before, something I found in the library, or an exhibition I visited. For my last series, I often went to the Louvre, looking at Renaissance paintings, especially the dresses and costumes, and also Degas’s dancer series. Each time I see something I like, I memorise it, store it in my own archive, and later it reappears in my drawings. Recently, I’ve also been very drawn to the world of carnival and circus, because it shows so clearly how reality and performance come together.

NM: You grew up with Chinese, Hungarian, and Spanish heritage in France. How has this background shaped your perspective?

Adèle Aproh: My family is very multicultural. My mother’s parents came from China during the Cultural Revolution, so she grew up in Paris. On my father’s side, my grandmother is Spanish and my grandfather Hungarian; they also met in Paris. Part of my family later returned to Spain. So I grew up with a mix of cultures – French, Chinese, Spanish, and Hungarian. Holidays were sometimes in Paris, sometimes in Spain. I have cousins in the U.S., Spain, and China, and most of them don’t speak French, so gatherings were always full of different languages. I think that openness shaped me a lot. In my drawings, you can feel that mix, not literally from my heritage, but in the way I absorb influences. Early on, I was very inspired by Japanese and Chinese culture; Miyazaki was a big influence. Now my world is more blurred: comics, cinema, fashion, carnival, history. It’s a bit of a bazaar, but also structured. I like to call it an organised mess.

NM: You’ve described your work as both fascinating and disturbing. Do you want to provoke audiences?

Adèle Aproh: No, I don’t draw with the idea of provoking. For most of my life, I drew only for myself. I didn’t share my work, not even online. So when I began to exhibit, it felt very exposing, almost like being naked, because my drawings are full of personal references and intimacy. People sometimes interpret them as feminist or political. I am a feminist, but for me the work is personal. Each drawing contains many stories from me, even if they’re not explicit. When viewers bring their own interpretations, it helps me take a step back and hide a little behind their readings. In my early works, my characters were more childish and covered, because I was shy and afraid of being too visible. As I became more comfortable sharing my art, my women also became more confident, with their bodies, the way they dress and undress. I grew more comfortable with nudity, skin, and femininity. When I look back at drawings from two years ago compared to now, the difference is striking.

NM: Does drawing help you process things about yourself as well? For example, I read about Entangled and how it helped you untie knots in your mind.

Adèle Aproh: Yes, oh yes. Drawing has always been a way for me to process. I’ve been pretty anxious since I was a teenager, maybe even before, and drawing became my safe place. It’s the one practice where I could sit for hours, focus, and forget everything that was bothering me. Entangled is a very direct example; it was really a depiction of the anxiety I was going through at the time. It’s also why I don’t always talk about it when I present my work, because it still feels very intimate. I’d rather depict it in a drawing than try to put it into words.

I don’t really like talking or writing about myself. I don’t take myself that seriously in daily life, so drawing became a way to invent my own language. Sometimes not being understood is fine, you know? It’s like staying in my own bubble. But it’s also a paradox: on one hand, I want to stay hidden behind a curtain, and on the other, I’m showing my world to the world. I’m still figuring out that balance – how to not show too much, but still show enough so people can enter the work. What helps is that my drawings are very narrative and figurative, not overly conceptual, so people can easily bring their own interpretations. And sometimes they do the job for me. They tell me what they see, and often it makes sense in ways I hadn’t even noticed. That’s something I love – that the drawing becomes theirs too.

NM: Is there a story like that which stayed with you, where someone interpreted your work in a way that surprised you?

Adèle Aproh: Yes, many times. A lot of people think my work is very political, especially feminist, like women taking over the world. I don’t actively set out to make political work. Of course, I have opinions; I am a feminist, but I’m not intentionally building political messages into my drawings. Still, I understand why people read them that way. And in a sense, it’s partially true, because everything is political, whether you want it or not.

NM: Do you think art should be political?

Adèle Aproh: I don’t know if it should. It can be, and that’s important; artists who want to work politically should do it. But I also think it’s important to have the choice not to. Still, as we say in French, everything is political. Even if you don’t intend it, it becomes political in some way.

NM: Your drawings are described as “stories within stories.” Do you imagine narratives before you start?

Adèle Aproh: It depends. For big drawings with many characters and details, I start with a rough composition sketch, but not very detailed. When I actually begin, I don’t know exactly where it will go. The drawing unfolds day by day. Each section is made depending on my mood, what I saw that day, and what I was thinking about. So if I had drawn it on another day, it might be completely different. That’s why I say they’re like stories within stories, each part has its own little thread. It’s almost like comic panels, each frame connected but also separate. Even I reinterpret them differently later, depending on when I look at them. That’s why I love working on large pieces: I can get lost in the details and let it evolve. It’s very instinctive, almost unconscious. I don’t overthink. I just follow where it goes. And that’s why it feels therapeutic.

NM: So drawing is like therapy for you?

Adèle Aproh: Yes. Since I was a teenager, I’ve been using drawing the way some people use a diary. I never kept a written diary. I couldn’t write about myself, but I drew. It was my way of building a world with its own rules, a place where I had control. That feeling of control is important to me. I’ve always been a bit of a control freak, and my anxiety comes from the fact that you can’t actually control life. As a teenager, I even had OCD. I’ve been treated for it, but it’s something that stays with you. Drawing helps me manage that. In my drawings, I decide everything—the detail, the composition, the colours. Of course, it can be frustrating too, because you never perfectly capture what you imagined. But even that is part of it. At least I’m deciding. I’m building my own world, and in that space I don’t think about what people will say. It stays mine.

NM: Do you feel you need to take it out of yourself, onto the paper, in order to separate from it?

Adèle Aproh: I think so, yes. But for me, drawing is therapy, mostly through the process itself. You spend hours on details, on colours, and it becomes a good exercise for the mind. It’s a way to disconnect. I don’t do meditation, but I imagine it’s the same. When you meditate, you try to let go of everything. Drawing does that for me. I shut everything out and focus only on what happens on the paper.

MN: Has a drawing ever surprised you, where you started one way, and it ended up somewhere completely different?

Adèle Aproh: Actually, it happens all the time. I usually begin with a rough sketch, but the final work never looks like it. It always takes another direction. I get impatient, curious to see how it will look in one or two weeks. My drawings never end up exactly as I imagined, and that’s what keeps it exciting.

NM: Last year, you had your first U.S. solo exhibition, Custom Made. Can you tell me about it? Did reactions feel different compared to Europe?

Adèle Aproh: It was actually my first solo exhibition ever, not just in the U.S., which made it even more exciting. I haven’t shown in France at all; I’ve mostly exhibited internationally, which still feels a bit crazy. I felt very lucky and also intimidated. I didn’t really have a process because I’d never prepared a solo show before. I just told myself: draw a lot. But I also wanted the exhibition to feel consistent, to tell a story. At the time, I was spending a lot of days in the library, gathering archives of costumes and uniforms. I focused on uniforms, and on hands, people dressing each other, helping, touching. I don’t really know why, but I find it fascinating to depict hands in action. Preparing for the show taught me discipline. I only had a few months, so I had to establish a rhythm and push myself.

Since then, I’ve done more solos and group shows. Because I didn’t go to art school, I never had those years of searching and experimenting in a structured way. Instead, I’ve been learning by doing, in a kind of accelerated way. When I look at drawings I did three years ago, they’re so different from what I make now. The influences are the same, but my work has evolved a lot. That’s motivating- it makes me want to keep going, to see where else it can lead.

NM: Speaking about the evolution of your work, from what I’ve seen and read, your earlier pieces celebrated a somewhat chaotic, feminine freedom, perhaps in the hedonistic scenes, like with the lobster. Then, for the Custom Made exhibition, there seemed to be more focus on uniforms and control. How do you see this evolving during your residency now? What’s the next emotional focus for you?

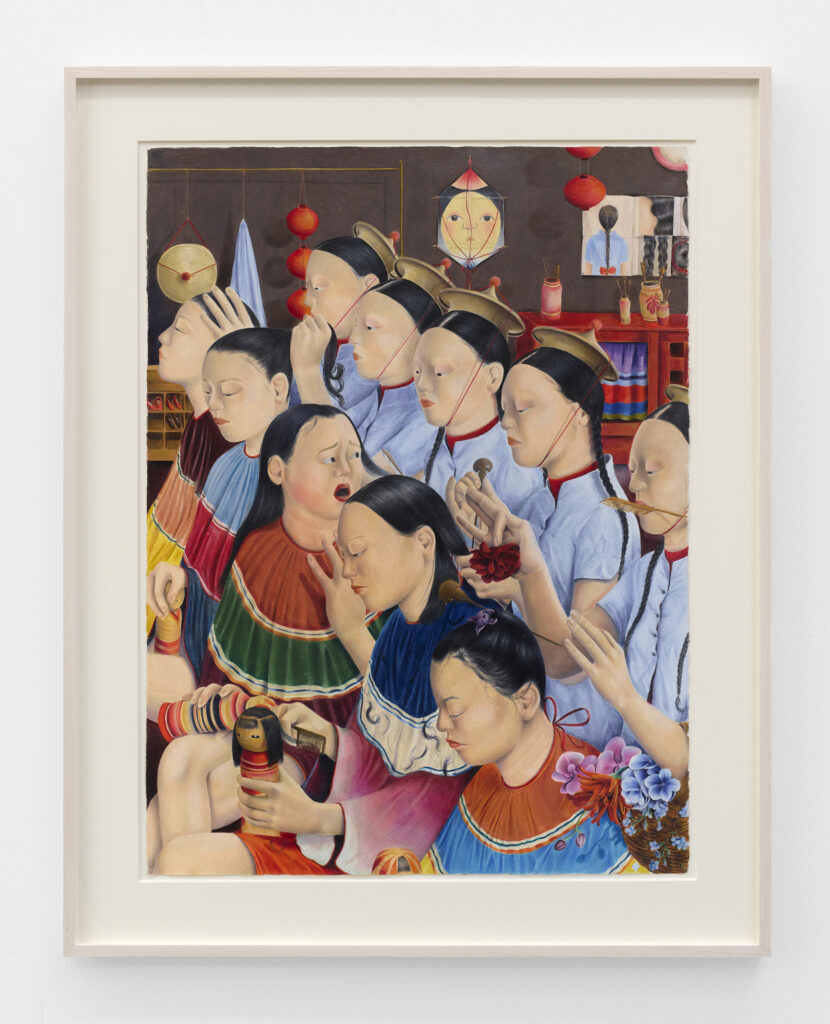

Handmade Pupa, 2024, 106x75cm, pastel on paper, courtesy of the artist and Scroll, New York

Adèle Aproh: I think I keep the same influences and themes, but I explore them differently. My drawings have grown with me, and I never really know where I’m going. Looking at the piece I’m working on now, it feels more Dionysian, more festive. When I observe what I’m doing, that’s actually what I see. Many of my recent drawings show backstage moments, people preparing, doing their makeup, helping each other, whether it’s backstage at a circus or some kind of show. Even I’m not sure exactly what it is. Is it theatre? Circus? Pole dancing? We don’t really know. Lately, I’ve been focused on characters preparing themselves, doing their makeup, dressing, and helping one another.

NM: Like some kind of ritual, perhaps?

Adèle Aproh: Yes, definitely. There’s ritual in my drawings. I’ve always used ritual as a way to feel control and safety, and that naturally carries into my work. People need rituals to feel supported, and I think I use that in my practice too. That’s why my work can feel therapeutic: if you analyse it closely, it’s all remedies for my own anxiety.

NM: You’re untying the knots?

Adèle Aproh: Yes, I think so. But I also just enjoy doing it. That pleasure is therapeutic in itself. Doing something you like is essential. And it’s a privilege to make a living from it. I feel lucky to be here, to be able to work on my art, to make a living from it.

NM: Tell me about the Mack Art Foundation residency. Sometimes residencies can push an artist’s boundaries. Was there a new medium, scale, or concept that you explored there?

Adèle Aproh: The reason I started the large drawing, Rush Hour, was that I wanted to begin the residency with it. But realistically, I couldn’t do another one of that size now; I know how much it takes, and I’d have to work day and night. This was actually my first residency, so before coming, I didn’t have a strict plan. I’d been so absorbed by this big drawing.

During the residency, Rush Hour was exhibited at The Hole in their group show, Guest of a Guest, which was really exciting. Another work I completed there, Wigs and Booze, was included in Christine’s exhibition Beyond the Present: Collecting for the Future at the Southampton Cultural Center. I even did a small collaboration with Balmain during a collection presentation at Christine’s house in the Hamptons, completely unexpected, but such a fun opportunity.

After finishing the big piece, I focused on making smaller drawings and started working with my gallery, Scroll, on exhibiting them. I also brought a couple of drawings from my Scroll show last year to the residency, and when I looked at them again, I thought, “I don’t like them anymore.” Honestly, sometimes even the day after finishing a drawing, I feel that way. It pushes me to keep going, to start something new.

NM: So it’s also about accepting what you can’t change anymore?

Adèle Aproh: Exactly. People sometimes ask, “Do you feel sad when you have to give away work?” And I say, “Oh no.” I’m not the type to keep my drawings at home; it would never happen. I like making them, but I wouldn’t hang them in my apartment. It would feel too embarrassing. I just move on to the next thing.

NM: So you explored a new scale during the residency?

Adèle Aproh: Yes, a huge scale. The residency was very convenient and comfortable. There was this big space with glass walls, and Christine was incredibly caring and helpful. I felt spoiled; it was such a great environment to work in.

Being in New York was also a huge part of the experience. I came last year for my show and knew I had to come back for longer. So when I heard about this residency, it felt like a unique opportunity to work here under the best conditions for a good amount of time.

And New York itself is endlessly inspiring. There are so many galleries and artists here. What sharpens my drawing is constantly seeing other art, even on social media. I’m always looking, calling up artists, studying their work, saving images. While I was there, I toured exhibitions nonstop. The city nourishes my art. Sometimes you see so much good work that you think, “I have to do better.” That pressure motivates me. Being surrounded by so much art and so many artists was incredibly energising.

NM: If you could think of a dream collaboration – fashion, film, performance, or anything that would take your work to the next level or a new direction, what would it be?

Not too Short, 2024, 76x56cm, colored pencil on paper, courtesy of the artist and Scroll, New York.

One of Them, 2024, 76x56cm, colored pencil on paper, courtesy of the artist and Scroll, New York.

The Mask Experience, 2024, 40x30cm, colored pencil on paper, courtesy of the artist and Scroll, New York.

Adèle Aproh: There is something I love. Stop-motion is an animation technique where you take pictures frame by frame. I’ve always been fascinated by it, and I think it’s linked with comics and storytelling. I’d love to make my own little stop-motion animation one day, though it requires so much time, money, and information. I’ve been looking for stop-motion courses in Paris, so it’s somewhere in my mind. That’s definitely something I’d like to try.

And also collaboration in fashion. I love fashion, so maybe one day… Chanel, for example. Lately, I’ve been inspired by their collections. I often scroll through Fashion Week shows and check their website.

NM: Fingers crossed. Good to dream. I know you also did some drawings related to tarot cards. If you could draw a tarot card for your future self, what would it be?

Adèle Aproh: The Fool. The crazy guy. Funny story: I started that series when I quit my job. I wanted to do a series, and I was interested in the iconography, not really spiritually, but visually. It was a way to interpret in my own way, something playful. I never finished the series because group show opportunities came up, and I had to switch to something else.

NM: Do you think you would go back to it?

Adèle Aproh: No, I don’t generally go back to things I’ve done. I always go forward. It’s funny how it started, but I don’t have any of those drawings anymore, not even in Paris.

NM: You mentioned rituals earlier, and I read in an interview that when you start working, you have coffee and listen to podcasts. What podcasts?

Adèle Aproh: I listen to French public radio, our national radio. They have so many shows on different topics. I listen all day. I share my studio with my boyfriend, who also works creatively, and sometimes he goes a bit crazy because I have podcasts on constantly. But it helps me, like turning on the TV in the background while doing something else. I don’t actively listen all the time, but it’s there. I use a lot of true crime podcasts, and I have a lot daily.

NM: So coffee and podcasts are the two essentials for work?

Adèle Aproh: Yes, but I have to control coffee, I’m sensitive to it. My dad’s a doctor and always warned me. Too much gives me palpitations. But coffee and podcasts—those are my essentials, and then I can work all day. Sometimes I listen to music as well.

NM: Do you have any advice for your younger self when you made the switch from corporate life to the art world?

Adèle Aproh: I don’t think I would give advice, because I was in a good place when I quit my job. I didn’t know anything about the art world, how it worked. I was kind of naive and very optimistic. Not that I’m not optimistic now, but I’m more realistic about the real art world. The fact that I was so optimistic and motivated, without really knowing where I was going, gave me the right push at the right time. So no, I wouldn’t give myself advice. The fact that I didn’t know anything helped me just dive in. If anything, the advice would just be: do it. Looking back, it was far away and unknown, but I was ready for it.

NM: Do you think that if you had known more, you might have had more doubts about doing this?

Adèle Aproh: Not more doubts, probably. I might have done things differently, but it’s hard to tell. Back then, I didn’t have galleries or opportunities, so I wouldn’t have had the same path. Not knowing was sometimes the best way to find my own way. Also, I didn’t go to art school, so I didn’t have a frame. I think if I had gone, I might have worked more for others or teachers than for myself. Maybe it would have changed the way I work, not necessarily badly, but I’ll never know. I’m happy with how things turned out. So the advice remains: just do it.

Rush Hour, 2025, 135x150cm, coloured pencil on paper, courtesy of the artist and Scroll, New York

The Harvest, 2024, 56x76cm, coloured pencil on paper, courtesy of the artist and Scroll, New York

Study for a Masquerade, 2024, 106x75cm, coloured pencil and pastel on paper, courtesy of the artist and Scroll, New York

Pictured Adele with Christine Mack